There are numerous religions in the world. Some, such as Christianity and Islam, have large numbers of adherents, while there are also countless forms of animism and folk religions. One major opportunity to acquire knowledge about religions with which we are not usually closely involved is, first, school classes, but another major opportunity is media reporting. Consequently, the reporting we casually see and hear in everyday life likely has a strong influence on shaping our interest in and images of each religion. With this in mind, we set out to clarify the tendencies in Japanese international news coverage related to religion by analyzing the volume of reporting by religion and the contexts in which each religion is reported.

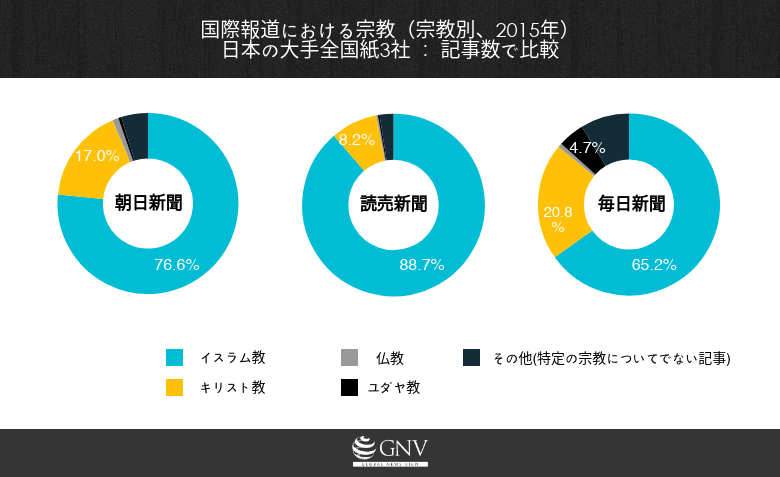

First, across all international news articles in the three major national dailies—the Asahi Shimbun, the Yomiuri Shimbun, and the Mainichi Shimbun—we extracted the share of articles “related to religion.” (For details of the methodology, see Footnote *1.) We then categorized those articles by religion; the graphs summarizing the results are shown below. (For details of the methodology, see Footnote *2.)

As you can see, all three papers carry overwhelmingly more articles about Islam. In the Yomiuri Shimbun, the share even exceeds 85%. The next most-covered religion is Christianity, a tendency common to all three. Articles on Judaism, Buddhism, and Hinduism trail far behind. Now, let’s look at the global distribution of religious populations.

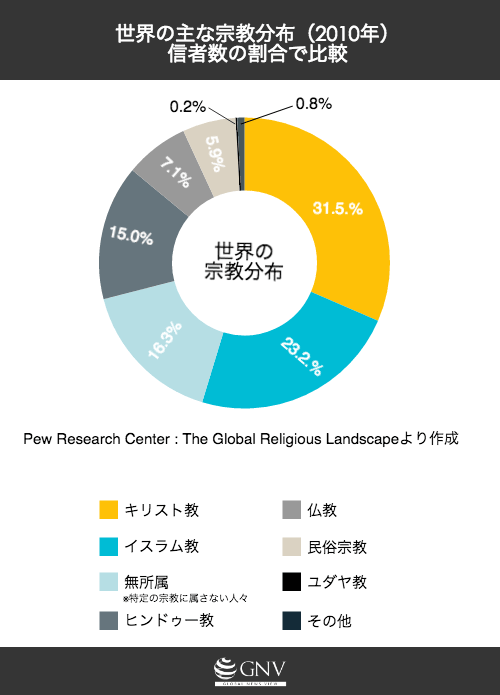

31% are Christians, 23% are Muslims, 15% are Hindus, and 7% are Buddhists. As this shows, there is a mismatch between the share of adherents and the volume of coverage. It does not appear that coverage varies in proportion to the number of adherents.

So why are there so overwhelmingly many articles about Islam? One major reason is the armed group “Islamic State,” which has occupied parts of Syria and Iraq. In this analysis, we deem articles whose headlines include terms that evoke religion to be “related to religion,” so articles about Islamic State are counted under the category of Islam. However, many of those articles concern the activities and expansion of an armed group, which is distinct from coverage of religion itself, such as Islamic doctrines or practices. Therefore, when we exclude articles whose headlines include “Islamic State,” the volume of coverage by religion is as follows.

Even after excluding articles whose headlines include “Islamic State,” articles about Islam remain the most numerous, accounting for over 40% in the Mainichi Shimbun and over 50% in both the Asahi Shimbun and the Yomiuri Shimbun. Moreover, in all three papers, articles about Islamic State made up a large portion of the religion-related coverage: specifically, 47.9% in the Asahi, 39.4% in the Mainichi, and as high as 72.0% in the Yomiuri. Here too we can observe a pronounced imbalance in how religion is treated in the news.

Up to this point we have looked at the volume of religion-related articles, but next let’s consider the content of coverage for each religion. For example, in reporting on Islamic State, religion is often discussed in a negative context involving violent or destructive acts such as terrorism and conflict. Accordingly, GNV created a field called “presence of violence” in our proprietary database and classified articles based on their headlines. (For details of the methodology, see Footnote *3.) On that basis, the proportion of articles covering topics involving violence among all “religion-related” articles was 48.9% in the Asahi, 47.6% in the Yomiuri, and 37.2% in the Mainichi. In all three papers, roughly 40–50% of religion-related articles were reports of “bad” news accompanied by violence.

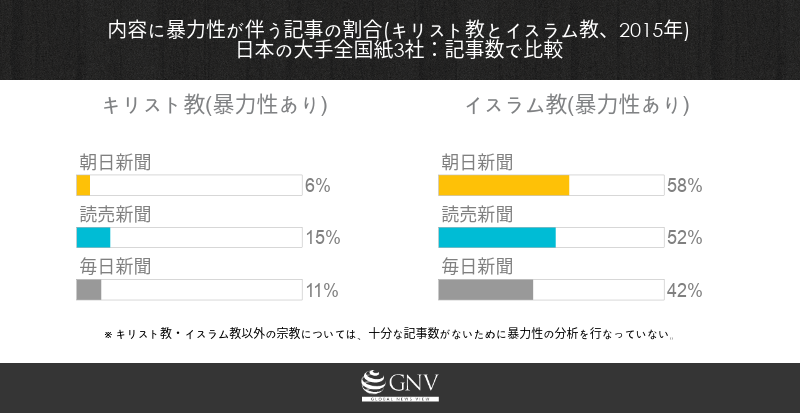

We also compared the prevalence of violence by separating articles about Christianity and Islam. The results are as follows.

As is immediately apparent, there were more articles with violent content about Islam than about Christianity. Here again, we ran an analysis excluding articles about Islamic State. In the Asahi, the share of articles involving violence decreased when Islamic State pieces were removed (58.3%→51.9%), but in the other two papers the share actually rose when such pieces were excluded (Yomiuri: 52.2%→54.5%, Mainichi: 42.4%→53.5%). Because many reports about Islamic State discuss measures taken against the group, the balance likely differs by newspaper, producing these results.

What we would like to highlight here is the context in which Christianity appears in articles involving violence. Among the 13 such articles across all papers that were judged to involve violence, we found that in 12 of them the Christian side appeared as the “victim.” (Example headlines: “Ninety Christians abducted? Minority villages attacked in northeastern Syria” (Asahi Shimbun, February 26, 2015), “University attack leaves 70 dead; extremists target Christians in Kenya” (Asahi Shimbun, April 3, 2015).) By contrast, in contexts where Islam appears, a majority of the articles portray the Islamic side as the “perpetrator” (Mainichi: 74%, Asahi: 70%, Yomiuri: 59%).

This trend is troubling. It overly emphasizes a skewed dichotomy in which Christianity is always the victim and Islam is always the perpetrator. In other words, it risks spreading a biased and erroneous perception that Muslims are people with dangerous ideas. One might wonder whether, as a matter of fact, Muslims are often the perpetrators in conflicts or violent incidents. But is that really true?

We therefore need to consider conflicts in which adherents of other religions are the perpetrators and Muslims are the victims. For example, in the conflict in the Central African Republic—one of the armed conflicts that caused the world’s worst humanitarian harm in 2015—large numbers of Muslims were massacred by armed groups composed mainly of Christians. In Myanmar, the Rohingya, who are Muslim, are persecuted by communities and a regime centered on Buddhists. Moreover, in many conflicts involving Islam, religious antagonism is not the sole factor. Armed conflict is, by its nature, a social phenomenon in which various factors—such as power struggles and the distribution of wealth—intertwine in highly complex ways. Consequently, there are also many cases in which both the perpetrators and the victims in a conflict are Muslims. To affix only the label of “religious conflict” to such cases is, to say the least, overly simplistic.

This analysis has revealed that there is a substantial imbalance in the volume of coverage of each religion, and that there is also a significant difference in the contexts in which Christianity and Islam are reported. Given the mass media’s major role as a source of information about religion, heavily skewed reporting directly contributes to the formation of heavily skewed (i.e., mistaken) public perceptions. Religion is not only an object of faith for believers and communities; it also plays various roles in daily life. If we ignore that and try to view religion solely through the extreme lens of being a cause of conflict or violence, we lose sight of the facts surrounding religion. Of course, it is necessary for reporting itself to change so as not to be trapped by images and dichotomies. But there is also something we, as recipients of information, can do right now: rather than swallowing media narratives whole and labeling particular religions or their adherents as good, bad, or frightening, we should make the effort to understand each religion and its surrounding circumstances correctly.

Writer: Sota Dokai

Graphics: Hiro Kijima

0 Comments