There are as many as 193 countries in the world, and as in Japan, politics, the economy, and society are in motion every day across the globe, with incidents and accidents occurring. There are also regions where wars and conflicts are taking place. But do the news stories we see and hear every day really reflect the world as a whole? For example, picture the continents on a globe: the Americas, Africa, Eurasia, Oceania, and Antarctica. Isn’t it true that the regions we often hear about in the news are just a tiny fraction of these? Africa, Central Asia, Oceania, Latin America—how often do stories from these regions make the headlines? In this article, we examine what kinds of biases exist in Japan’s international news coverage.

We analyze Japan’s international news coverage by focusing on the volume of reporting by region and by country. The data consist of international news articles from Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri Shimbun, and Mainichi Shimbun in 2015. Regions are divided into six—Asia, Africa, Oceania, Europe, North America, and Latin America—following the standards of the UNSD (United Nations Statistics Division). Reporting volume is measured by the number of characters in the articles. For GNV’s definition of international news coverage, see “GNV Data Analysis Method [PDF].”

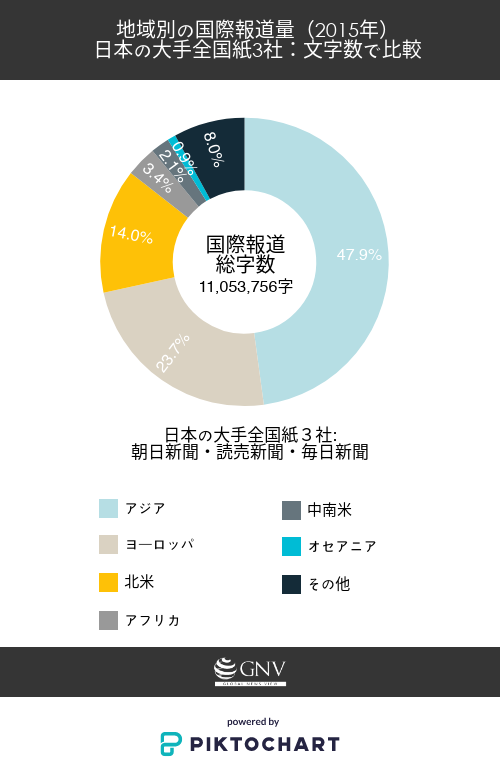

First, let’s look at reporting volume by region. Figure 1 shows the share of reporting by region. Asia accounts for an overwhelming amount, followed by Europe and North America. Even when the reporting volumes of all 87 countries in Africa and Latin America are combined, they amount to only 5.5%, not much different from that of a single country—France (5.2%).

Then, in these regions with low reporting volumes, which countries are covered the most, and what is being reported? In Africa, the most reported country is Tunisia, ranking 21st overall. Many of the stories concern terrorism. In particular, in 2015 there was extensive, detailed coverage of the museum attack that occurred in March. In Latin America, the most reported country is Cuba, ranking 19th overall. Most of the coverage concerns the normalization of diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba.

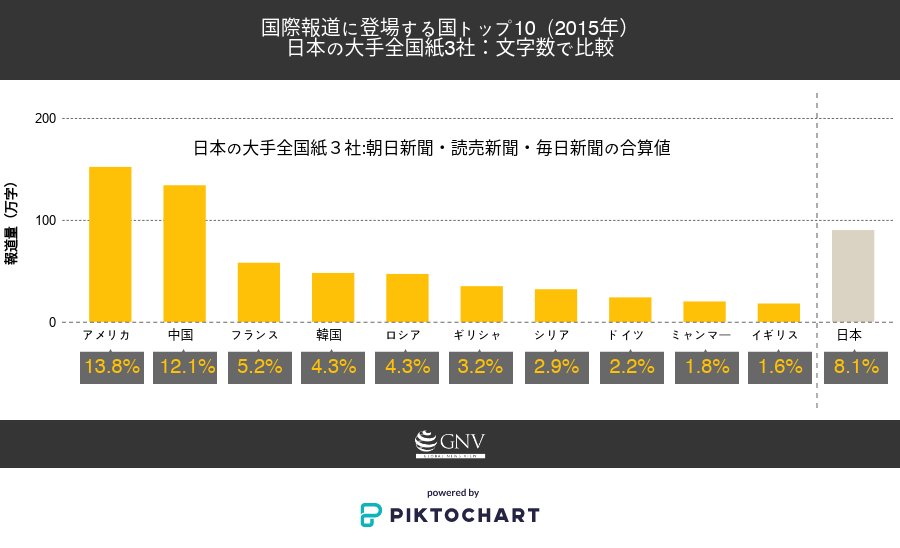

Next, let’s look at reporting volume by country. Figure 2 shows the top 10 countries with the highest reporting volume in international news in 2015. For comparison, it also lists the number of characters and the share of international news related to Japan.

What stands out first is how much of the international news relates to Japan. If you count the Japan-related international reporting shown at the far right of this graph within the ranking, it would place third—that’s how much there is. This is because stories about Japan’s relations with other countries—such as Japan–U.S. relations—and reports on incidents overseas involving Japanese nationals are more likely to be covered. Because reporting about Japan naturally attracts high attention domestically, it receives emphasis even within international news. Among Japan-related countries, those that rank include China, South Korea, the United States, and Russia—countries that are politically and economically, or geographically, close to Japan.

Dividing these top-reporting countries by region, there are four in Asia, five in Europe, and one in North America. No countries from Africa, Oceania, or Latin America make the list. So what characteristics do the most-reported countries have? One is that they tend to have strong political and economic ties with Japan on a day-to-day basis. Another is that the higher a country’s economic status, the more likely it is to be reported on. Comparing the top 10 countries by GDP in 2014 with the top 10 by reporting volume, five overlap: the United States, China, France, Russia, and Germany. Greece and Myanmar also appear in the top 10 this time. Greece received extensive coverage as the source of the European economic crisis and as a party to the subsequent economic negotiations. Myanmar was covered as a Southeast Asian country with strong political and economic ties to Japan undergoing major political change, with attention to moves toward constitutional revision, the general election, and the Rohingya as migrants.

However, a large GDP does not necessarily mean a large reporting volume. Among countries with large GDPs, some have small reporting volumes—India and Brazil, for example. Their GDPs rank 9th (Brazil) and 7th (India) in the world, but their reporting volumes are just 0.4% and 0.7%, placing them 35th and 24th, respectively (The World Bank, World DataBank). Both countries are large not only in GDP but also in population: India has 1.3 billion people (2nd in the world) and Brazil 200 million (5th in the world).

Why do these two countries, “large” in many respects, rarely make the pages? Looking at trade volume with Japan, India and Brazil fall far below the United States, China, and Europe; this may be one reason. Geographic distance may also be a factor in Brazil’s case. Another possible factor is their current state of “poverty.” In terms of GDP per capita, Japan is at 32,500 USD, whereas India and Brazil are at 1,600 and 8,500 USD, respectively. On average, these can be considered countries with relatively low living standards. This study also found that coverage of countries facing poverty is generally sparse. It may be that countries with living standards similar to Japan’s—those that are easier to understand or picture—are judged to be more likely to attract people’s interest.

This analysis clearly shows that there is a large gap between regions that are covered and those that are not in Japan’s international news. In particular, the paucity of coverage of Latin America and Africa is evident. There is also a tendency for countries with deep ties to Japan to be reported on more, and it may be that wealthier countries receive more coverage than poorer ones. As globalization advances and relations with regions around the world inevitably deepen, can such informational bias be overlooked? If news coverage changes, it may greatly help convey the realities of world affairs and deepen readers’ understanding of the world.

Writer: Miho Horinouchi

Graphics: Mai Ishikawa

0 Comments