In 2023, the world’s largest iceberg in Antarctica began to drift away from the continent due to melting (※1). This iceberg boasts an area of 4,000 square km, which is about 1.5 times the size of Luxembourg. This event is due to the rapid rise in temperatures in Antarctica. In some places, the magnitude of warming is about five times the global average.

Antarctica faces serious environmental problems while existing under harsh natural conditions. However, because it is crucial for understanding the world’s climate and nature, it has become a target of research for many countries. Antarctica has no indigenous peoples and has not experienced armed conflicts over territory. One can say peace has been maintained through international cooperation. However, such a peaceful state may not continue indefinitely, and various issues beyond environmental problems are arising.

This article explains an overview of Antarctica and its position in the world, then examines what problems are emerging and analyzes how Antarctica may change in the future under these circumstances.

A chinstrap penguin walking on ice (Photo: Reeve Jolliffe / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

目次

Geography of Antarctica

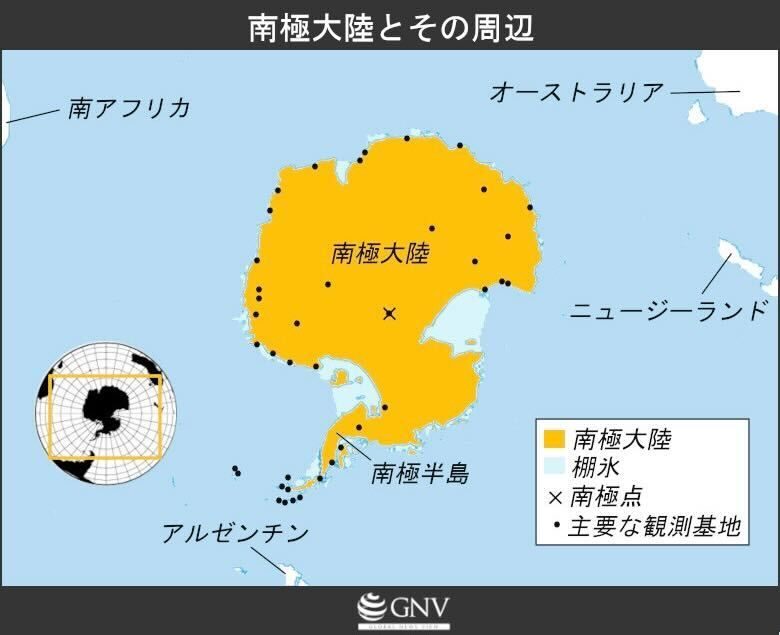

Antarctica refers to the Antarctic continent and the surrounding seas and islands. Strictly speaking, areas south of 66.5 degrees south are called the Antarctic Circle, and areas south of 60 degrees south are called the Antarctic region. First, we will describe the geographical conditions of this region. The Antarctic Circle is a vast region that covers 20% of the Southern Hemisphere and includes not only the Antarctic continent but also the Southern Ocean. The area of the Antarctic continent is about 14 million square km, twice the size of the Australian continent. The Southern Ocean covers about 20 million square km . The closest country to the Antarctic continent is Argentina, at approximately 1,000 km away. However, it is about 6,000 km from the nearest major city, making it a land isolated from humans.

The region is characterized by low temperatures and the fact that, consequently, it is covered in ice. In Antarctica, temperatures vary greatly between the coast and the interior. Along the coast, temperatures drop to minus 40℃ around July (winter) and rise to around 10℃ in January (summer). In the interior, they can drop to minus 80℃ in winter and rise to minus 30℃ in summer. As a result, 98% of the Antarctic continent remains covered in ice even in summer, and in winter even the surrounding seas freeze. The ice covering Antarctica is called glaciers or ice sheets, and the state in which the sea is frozen in winter is called sea ice. There is also ice called ice shelves, which are formed when land-based glaciers or ice sheets are pushed out into the sea and remain afloat.

Antarctica is also extremely dry, with an average annual snowfall of about 150 mm. Thus, despite its ice-covered landscapes, it is actually the world’s largest desert (※2).

Although Antarctica is covered in ice and may seem at a glance to host only animals such as penguins and seals, large numbers of microorganisms, krill, and jellyfish exist beneath the ice, forming a rich ecosystem. The Southern Ocean is considered one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, with not only whales but also vast numbers of plankton and microorganisms present.

History of Antarctica and the Antarctic Treaty

Antarctica is far from where people live and its harsh nature means there are no indigenous peoples, but after the continent’s discovery it came to be utilized and managed to some extent by humans. Let us look at how this situation arose.

The existence of the Antarctic continent was first confirmed in 1820 ( ※3). Subsequently, various countries sent expeditions aiming to explore Antarctica. In 1911, an expedition led by Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole for the first time. As the value of utilizing Antarctica became recognized in the 20th century, countries began asserting territorial claims. First, in 1908, the United Kingdom claimed sovereignty over part of Antarctica. By 1950, seven countries in total—New Zealand, France, Australia, Norway, Argentina, and Chile—had followed suit. However, some areas claimed by different countries overlapped, creating the potential for territorial disputes. In 1948, the United States proposed a UN trusteeship for the seven countries to ease tensions in Antarctica, and Chile proposed freezing territorial claims for 5 to 10 years, but none of these led to agreement. In 1950, the United States again proposed freezing territorial claims and establishing a governance framework for scientific cooperation, but because the Soviet Union was excluded from this proposal, it was rejected by the Soviets. The UK then sought to bring the matter before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and various countries attempted to discuss it at the UN.

This stalled process shifted in 1958. That year, countries began building observation stations under a research program in Antarctica called the International Geophysical Year (IGY). As part of this, the Soviet Union established an observation station at a location farthest from the sea and hardest to reach. At the time, the United States and the Soviet Union were in a state of Cold War rivalry, so the United States saw the Soviet action as a show of power and worried it might expand its military presence in Antarctica. Consequently, the U.S. military argued that the United States should assert territorial claims, while the State Department opposed this, arguing that showing force in Antarctica would be meaningless in dissuading the Soviet Union. Ultimately, the State Department’s view prevailed, and the United States decided to invite other countries to discuss the use of Antarctica. The United States invited the 7 countries that had asserted territorial claims and 4 countries that had participated in the IGY, and convened a conference. As a result, the Antarctic Treaty was concluded in 1959.

The Ceremonial Pole, one of the markers indicating the South Pole (Photo: NSF/Josh Landis, employee 1999-2001 / Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

The Antarctic Treaty is a multilateral treaty that provides for the peaceful use of the Antarctic region, cooperation for research, and the freezing of territorial claims. It was initially concluded by 12 countries in 1959 (※4), and as of 2024 it has been signed by 56 countries. Its scope applies to the Antarctic region, that is, all areas south of 60 degrees south latitude. The Antarctic Treaty is described in more detail below.

First, Article 1 stipulates the peaceful use of the Antarctic region. Military activities are therefore prohibited in Antarctica. Here, “military activities” include the construction of military bases and the use of weapons. However, the use of military personnel or equipment for scientific or other peaceful purposes is permitted.

Articles 2 and 3 ensure freedom of scientific investigation and require cooperation among countries, as well as the exchange and free use of research results obtained in Antarctica. As a result, a total of 29 countries have research institutions in Antarctica, with a total of 70 research stations established. These 29 countries are the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties, which actively conduct scientific research and hold decision-making power at the regularly convened Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings.

Article 4 provides that while the Antarctic Treaty is in force, assertions of territorial sovereignty in the Antarctic region are frozen. Thus, the claims of the original seven countries and any new claims by other countries are set aside. These Articles 1 through 4 are the treaty’s key provisions.

The U.S. Palmer Station researching radionuclides (Photo: The Official CTVTO Photostream / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0 DEED])

Beyond these, the Antarctic Treaty contains various other provisions. Among the most significant is denuclearization. Antarctica is the first region in the world where denuclearization was codified. Under the Antarctic Treaty, denuclearization is stipulated in Article 5, which prohibits any nuclear explosions and the disposal of radioactive waste. In the treaty’s initial discussions, nuclear explosions for scientific research were to be permitted. However, Argentina began arguing that all nuclear explosions should be banned, and Southern Hemisphere countries supported this stance. The United States opposed the ban, but ultimately agreed in order to eliminate the possibility that the Soviet Union could bring nuclear weapons to Antarctica and expand its influence; nuclear weapons were thus completely banned in Antarctica.

Since the Antarctic Treaty’s conclusion, several regulations related to Antarctica have been established. Notably, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol), signed in 1991, introduced the concept of environmental protection, which had been relatively weak in the original treaty. Specifically, it bans mineral resource extraction other than for scientific research and requires that any activities in Antarctica be assessed for their environmental impact. It also includes provisions for the protection of Antarctic flora and fauna and the prevention of marine pollution.

In addition, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS) was adopted in 1972 (※5), and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) (※6) was established in 1982, showing that new regulations and organizations have been created for Antarctica as needed.

An iceberg glowing blue due to underwater light conditions (Photo: NASA‘s Marshall Space Flight Center / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED])

Antarctica’s economic value and emerging tensions

As noted above, Antarctica has remained relatively peaceful due to the treaty framework. However, recognition of Antarctica’s significant economic value has grown, and its geopolitical importance is increasing. What economic value does Antarctica hold? We discuss this below.

First, it is believed that Antarctic mineral resources may exist potentially (※7). The Madrid Protocol prohibits the extraction of such mineral resources until 2048, but scientific investigations to confirm the existence of resources are not prohibited. Resources are projected to become globally scarce in the future. Countries are seen as eyeing Antarctic mineral resources in anticipation of possible extraction, and some countries are already conducting surveys. If this continues, Antarctic mineral resources could become a source of territorial disputes among nations.

Beyond mineral resources, the Antarctic region is rich in marine resources such as whales, seals, and krill. The capture of whales and seals in the Antarctic region began in the late 19th century, and their numbers are believed to have greatly declined due to overhunting by humans. Today, CCAMLR and CCAS impose restrictions on the capture of these animals. Krill are key to the food chain as they feed various animals. In addition to being feed for fish and other animals, they can serve as a good source of protein and lipids for humans and are increasingly important in modern fisheries. Krill are abundant in the Southern Ocean waters, and krill fisheries operate within CCAMLR limits. In terms of catch volume, Norway leads, while China and Russia are expected to expand their industries. However, reckless expansion could lead to overfishing—i.e., exploitation of marine resources—and ecosystem collapse.

Antarctica offers not only tangible resources but also various ways to derive benefits. One of these is bioprospecting. Bioprospecting involves obtaining genetic information from biological resources and using it to develop pharmaceuticals, agricultural products, and cosmetics. As Antarctica has remained largely unexplored, there may still be biological resources that could generate new benefits and that exist there. Countries and companies may pursue such industries.

Tourists heading to Antarctica by ship (Photo: Frans van Heerden / Pexels [Pexels License])

Tourism is another industry that has surged in recent years. Tourism to Antarctica began in the late 1950s. Initially, only a few hundred people visited per year, but between 2022 and 2023, 105,331 people traveled to Antarctica for tourism. People choose Antarctica as a travel destination to see its majestic nature and various national research stations. Tourism to Antarctica is regulated. The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), founded in 1991, regulates the industry to ensure that tourism is safe and environmentally responsible. Visitors must also comply with the Antarctic Treaty, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (※8), and the Guidelines for visitors to Antarctica. Conflicts may arise over which countries take the lead in tourism and profit in which regions of Antarctica from this perspective.

Thus, the resources and industries in Antarctica are valuable to many countries. In recent years, there have been warnings that, even within the framework of the Antarctic Treaty, tensions in international relations over Antarctica may rise. There are also moves that follow this trend. In 2018, the Australian government announced a plan to build a large runway and associated infrastructure near Australia’s Davis Station. With this runway (※9), Australian aircraft would be able to land and take off in Antarctica year-round. It would also enable flights from Australia to reach Antarctica in 6 hours. This would greatly improve logistics for personnel and supplies, delivering significant benefits for scientific research.

However, it has been pointed out that a geopolitical strategy lies behind this move. The plan is viewed as counterproductive to research activities when considering its negative environmental impacts on Antarctica. Moreover, because a runway would make transport and logistics to Antarctica more convenient, even scientists—who should benefit from improved accessibility for research—are reportedly opposed to the plan.

Despite this, the Australian government may be pursuing the runway to counter China and Russia, which are increasing their presence in Antarctica by intensifying research activities. Regardless of Australia’s aims, the runway’s construction could spur other countries to compete by building similarly large infrastructure. If that happens, Antarctica’s natural environment could be destroyed.

As discussed above, Antarctica hosts various resources and industries. At the same time, if countries compete for these rights, conflicts could arise in a place that is supposed to be used peacefully.

A U.S. government aircraft transporting supplies and people to a base (Photo: U.S.Department of State / Rawpixel [Free U.S Government Image])

Environmental problems affecting Antarctica

Environmental issues in Antarctica are also serious. Notably, Antarctica is markedly affected by climate change, which impacts the entire world. Below we explain the environmental problems Antarctica faces.

Temperatures in Antarctica are rising due to global warming. On the Antarctic Peninsula in particular, the average temperature has risen by 3℃ over the past 50 years. As noted at the beginning, the rate of warming is about five times the global average. One reason the warming rate is faster in Antarctica is the abundance of snow and ice. Snow and ice reflect more sunlight than the ocean or land; land absorbs sunlight. On continents without ice, most sunlight is absorbed by land, but in Antarctica much is reflected due to extensive snow and ice, limiting increases in ground and air temperatures. As temperatures rise and snow and ice melt, the area they cover shrinks, exposing more land to sunlight. This increases absorption and further raises ground and air temperatures. In 2022, a heat wave was observed with temperatures 39℃ above normal. This was the largest difference from normal recorded among heat waves observed on Earth.

As temperatures rise, Antarctic ice will, of course, melt and decrease. This affects the flora and fauna living on the Antarctic continent. Rising temperatures cause increases or decreases in populations and upset the balance of established ecosystems. Specifically, 65% of endemic Antarctic species may become extinct by the end of the 21st century. For example, endemic penguins may find it difficult to create the conditions needed for breeding as ice diminishes, leading to extinction.

Antarctica’s environment is also affected by the growth of tourism. Tourism pollutes the environment for several reasons. Ships are generally used to land in Antarctica. Fuel can spill into the sea, and vessels may collide with marine life at times. Additionally, such ships emit black carbon, a substance that accelerates ice melt. When it settles on Antarctic ice, it can increase melting. Moreover, when tens of thousands of people step onto the continent, they can trample precious mosses and plants, damaging them and affecting animal ecosystems as well. Thus, while tourism brings economic benefits, it can also cause environmental damage.

Tourists photographing penguins (Photo: GRID-Arendal / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED])

How climate change in Antarctica affects the world

Antarctica’s environment has suffered severe damage. At the same time, the climate change occurring in Antarctica—namely rising temperatures—also has major impacts worldwide. Below we explore these impacts.

The most concerning aspect of rising temperatures in Antarctica is the reduction of ice covering Antarctica, which leads to sea-level rise. In the Antarctic region, ice exists in various forms—sea ice, ice sheets, glaciers, and icebergs—and all are affected by warming. Let’s start with sea ice. Sea ice is the state of the sea being frozen and generally appears in winter. Because sea ice returns to water in summer, its melt does not increase the total volume of the world’s seawater and therefore does not directly contribute to sea-level rise. However, sea ice has the function of preventing land-based glaciers and ice sheets from melting and flowing into the sea ( ※10), so the loss of sea ice contributes to sea-level rise. This sea ice reached its lowest recorded extent in 2023, raising concerns about the impact of climate change.

Meanwhile, glaciers and ice sheets (※11) form when accumulated snow on land compacts into ice; when these melt, seawater volume increases and global sea levels rise. The Antarctic Ice Sheet, which covers much of the continent, is 1,200 m thick, and if it were to melt completely, global sea levels would rise by 60 m. In Antarctica, ice sheet loss is especially severe in the west and is expected to continue throughout the 21st century regardless of climate action, eventually collapsing. Likewise, icebergs are large pieces of ice that have broken off from glaciers and float on the sea surface; when floating ice melts, it increases seawater volume and contributes to sea-level rise.

Sea level has already begun to rise and is affecting the world. Even small increases can cause considerable damage. This includes coastal erosion, inundation of wetlands, and soil salinization. With larger increases, low-lying islands may be submerged and some island nations could face an existential crisis. Already, in low-lying areas at risk of flooding, some people have been forced to relocate as “climate refugees.”

Sea ice floating in the Southern Ocean (Photo: Reeve Jolliffe / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED])

Rising temperatures in Antarctica trigger various other phenomena beyond sea-level rise. First, warming alters ocean currents. If greenhouse gas emissions continue at current levels, deep ocean circulation could slow by about 40% by the 2050s. Normally, changes of this magnitude in ocean currents would take about 1,000 years, highlighting the abnormality of the current situation. Specifically, this circulation refers to the deep overturning circulation in the Southern Ocean, in which deep water around 4,000 m rich in oxygen and nutrients flows into the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans and rises to their surfaces. This change will significantly alter the distribution of nutrients and have major effects on ecosystems around the world, as organisms dependent on nutrients carried by the overturning circulation will face disrupted supplies.

Furthermore, a slowdown in deep overturning circulation leads to further loss of Antarctic ice, because slower circulation causes temperatures in the deep Southern Ocean to rise. This accelerates melting of Antarctic ice. In other words, the impacts of climate change further exacerbate climate change, creating a vicious cycle.

In addition, deep overturning circulation affects climate outside Antarctica. Specifically, it can alter sea surface temperatures, which in turn changes atmospheric moisture and shifts precipitation belts.

Future outlook

As discussed, although Antarctica is said to be used peacefully, it still harbors the potential for conflict and is severely affected by climate change—there are many problems. In this context, there are arguments that changes are needed to the Antarctic Treaty and other regulations and organizations surrounding Antarctica. While there are still unresolved territorial disputes, the Antarctic Treaty has worked very effectively in preventing armed conflict and enabling the peaceful use of Antarctica. Some therefore argue there is no need to change it at all. However, the Antarctic Treaty was drafted about 60 years ago, and the actors influential in Antarctica and worldwide then differ from those today. Thus, there is no guarantee that the current system can safeguard Antarctica’s peaceful use as new powers rise.

Scenery in Antarctica (Photo: Pedro Szekely / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

There is also a criticism that the current Antarctic Treaty contains too few provisions to address environmental issues. Although the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1991 and introduced an environmental protection perspective, some believe that even this is insufficient.

Before the question of Antarctic governance, much remains unknown about Antarctica’s environment, climate, and their mechanisms, and there is a view that research should be further advanced.

The Antarctic Treaty and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty can be revised in 2048 revised. By then, how will forces seeking revisions rise? And what will the future of Antarctica be? We will be watching closely.

※1 This iceberg calved from Antarctica in 1986 but had not moved away from the continent until now.

※2 Land with annual precipitation of 250 mm or less is considered a desert.

※3 In 1820, expeditions led by Edward Bransfield of the United Kingdom, Nathaniel Palmer of the United States, and Fabian von Bellingshausen of Russia each are credited with first confirming the existence of the Antarctic continent. However, which of the three expeditions discovered Antarctica first varies depending on how one defines “discovery,” and there are various theories.

※4 The 12 countries are Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South America, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

※5 Under CCAS, the capture and killing of certain seal species in Antarctica are prohibited to protect the ecosystem.

※6 CCAMLR is a commission established to prevent overexploitation of Antarctic marine life and ensure ecosystem sustainability.

※7 Mineral resources are believed to include minerals such as iron, copper, gold, silver, and molybdenum, as well as offshore oil.

※8 To ensure that visitors do not damage Antarctica’s scientific value or ecosystems, they are also required to comply with the Antarctic Treaty and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty provisions. Specifically, they are required to protect wildlife and not interfere with research.

※9 Australia already had a runway in Antarctica, but it was limited to summer operations and was far from the station.

※10 Sea ice around Antarctica protects glaciers and other ice from forces such as waves and wind, and by cooling the coastal atmosphere and lowering nearby temperatures, it helps prevent the melting of ice shelves.

※11 An ice sheet is a vast glacier and, like glaciers, contributes to sea-level rise.

Writer: Ayaka Takeuchi

Graphics: Yuna Miki

0 Comments