In Chile, a 2nd vote on the draft of a new constitution is scheduled for December 2023. The first vote was held in September 2022, but a majority voted against it and it was rejected. In response, a revised version will be put to a national referendum.

The current constitution was created under the regime of General Augusto Pinochet, who staged a military coup d’état in 1973. Roughly 50 years later, we examine why Chile decided to rewrite its constitution and what is happening in the country now.

People moving about in the capital, Santiago (Photo: Via em Santiago do Chile / picryl [Public domain Dedication (CC0)])

目次

Historical background

In what is now Chile, Indigenous peoples—broadly divided into several ethnic groups—originally lived in their own settlements, with the group known as the Mapuche at the center. Although they did not form a unified state, they sometimes joined forces to resist the Inca Empire and Spanish incursions. While Spain colonized Chile, they were exploited, for example by having land seized by settlers to run large estates.

Chile became independent from Spanish colonial rule in 1818, but foreign capital from Britain, the United States, and elsewhere flowed in, taking control of key domestic industries. At the same time, landlords and others tied to foreign capital monopolized wealth. With the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the 19th century, national revenues rose due to increased exports, mainly of wheat and copper. Land prices also rose, and the benefits accrued primarily to corporate and landowning proprietors. As a result, income distribution worsened.

Around 1930, under the impact of the Great Depression, the trade-centered economic model was reassessed. As industrial development progressed and labor movements became more active, the dominant social structure controlled by a few also began to be questioned.

The administration of Salvador Allende, which took office in 1970, pursued socialist policies—such as free medical care, large-scale redistribution of agricultural land, and nationalization of industries including copper—to address the problems noted above while maintaining a democratic form of government. However, it was overthrown in a coup three years later. The United States is widely seen as having actively intervened in this coup. Various backgrounds and reasons have been cited, including the Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union over political and economic policies, and the desire to protect the interests of major U.S. companies operating in Chile.

The Pinochet regime established by this coup adopted neoliberalism, under which the state imposed few regulations on domestic economic activity. This was devised mainly by Chilean economists who studied at the University of Chicago in the United States. The constitution created under Pinochet, which preceded this economic model, prioritized the interests of employers such as major corporations and the wealthy, and restricted workers’ rights to resist, including the right to organize. At the same time, public services such as pensions, infrastructure, and programs related to the social safety net were sold to private companies, shrinking the role of government.

From the perspective of gross domestic product (GDP), growth rates since the 1980s have been remarkable compared to the 1970s, and the neoliberal system greatly boosted economic growth. On the other hand, in addition to the problems mentioned above, the divide between haves and have-nots widened, resulting in the entrenched problem of inequality.

The road to a new constitution

Although Chile transitioned peacefully to democracy in 1990, post-democratization governments inherited the Pinochet-era constitution and neoliberal economic system. People suffering from unaddressed inequality staged large-scale protests repeatedly from the 2000s onward. However, the government of Michelle Bachelet, who served two terms as president from 2006 to 2010 and from 2014 to 2018, while attempting reforms in many areas, did not introduce measures that fundamentally changed the neoliberal policy orientation of the Pinochet era.

The protests that continued from 2019, compounded by the recession caused by COVID-19 in 2020, did not subside. Because the public’s discontent was directed at the neoliberal economic system that produced such inequality, the then-government led by Sebastián Piñera responded by holding a referendum on whether to rewrite the existing constitution that enshrined that system and to draft a new one. In the national referendum in October 2020, a majority voted in favor of rewriting Chile’s constitution. The following April 2021, an election was held to choose members of the new constitutional drafting convention. The vote resulted in a body composed with a 1:1 gender balance, and candidates not affiliated with political parties occupied the largest share. Members were drawn from a wide range of backgrounds, including activists for women’s rights and environmental protection, as well as lawyers and political scientists. Seats were also reserved for Indigenous representatives.

The constitutional assembly in session (Photo: Senado República de Chile / Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED])

Through this convention, a draft of the new constitution was submitted to the government in May 2022. It included numerous approaches to problems surfacing in Chile, such as guaranteeing rights related to freedom of labor, recognizing gender-equal participation in politics and access to education, social security including the pension system, legalization of abortion, and guarantees of Indigenous rights. However, as noted at the outset, in the referendum held in September of the same year, the draft was rejected, with about 62% voting against it. Various reasons have been cited, including claims that it was too radical to secure broad public support.

Toward a new administration

Since democratization in 1990 following the Pinochet military regime, Chile’s governments had been led by two grand coalitions—one center-left and one right-wing—each composed of multiple parties. Over time, however, these coalitions gradually lost support among people suffering from persistent inequality. In particular, the right-wing coalition that held power during the large protests in 2019 failed to win support in the popular elections for the constitutional convention, and it won less than one-third of the seats. Since proposals for the new constitution required approval by two-thirds of the convention, the right was unable to exert significant influence over its decisions.

Amid this political situation, radical left-wing parties gained popular support. Gabriel Boric, who won the 2021 presidential election and took office as the youngest president in South American history at age 36, belongs to these left-wing forces and heads the political alliance discussed below.

After studying law at the University of Chile in Santiago, he was elected president of the university’s student federation in 2011, becoming a core leader of the student protests. In 2014 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, one of the two houses of Chile’s legislature, and served as a deputy for four years. He did not belong to the two major coalitions; in 2016 he helped launch the political alliance Frente Amplio with other left-wing parties, expanding its influence and consolidating his political base.

President Gabriel Boric (Photo: Vocería de Gobierno / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

Announcing his run for president in 2021, he drew support by pledging to work on pension and health insurance reforms to reduce inequality. In the runoff held on December 19 of the same year, he won 55.8% of the total votes, defeating his right-wing rival, José Antonio Kast.

The new president’s agenda

In Boric’s first cabinet, 14 of the 24 ministers were women, occupying key posts including the interior, justice, and defense ministries. The government has been proactive in addressing issues such as discrimination against women and gender gaps. Specifically, it has launched initiatives to promote women’s economic independence, such as legally protecting the right to access daycare so that women can more easily balance childcare with participation in the labor market.

Another major initiative is an attempt to overhaul abortion policy. In Latin America, including Chile, women’s right to obtain abortions has long been restricted for religious reasons. For more details, please see this past GNV article. In recent years, with growing criticism of such restrictions from the perspective of protecting women’s lives, Chile passed a bill in 2017 lifting the total ban on abortion.

However, under that bill, abortion was only legal when the pregnant woman’s life was at risk, when the fetus was non-viable, or in cases of rape within 12 weeks (14 weeks for girls under 14). Moreover, because medical facilities were allowed to refuse to perform abortions, relatively few women could actually obtain the procedure. The Boric administration supported a new constitutional proposal to approve abortion unconditionally so that women could access abortions safely, freely, and legally, backing the effort. However, the draft’s rejection in September 2022 postponed resolution of this issue. The government is exploring measures from other angles, such as providing low-cost contraception.

The cabinet in March 2022 (Photo: Prensa Presidencia – Gobierno de Chile / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 3.0 CL DEED])

Beyond gender issues, the government is also addressing labor issues. It has raised the minimum wage and, to improve workers’ quality of life and rights, submitted a bill to shorten the workweek to 40 hours, which was approved by Congress in April 2023.

Furthermore, as part of plans to strengthen the social security system, the government introduced a bill at the end of November 2022 to carry out pension reform. The bill would shift from the existing pension fund administrator (AFP) scheme to a new public–private partnership system funded by employer and state contributions. Previously, private companies handled pension payments, which were based on the premiums contributors paid into those companies; as a result, differences in wages translated directly into disparities in benefits. The reform aims to end that practice by assigning a role to the public sector, budgeting for pension payments as part of the social security system, and ensuring broader coverage. Parliamentary debate on this reform has been postponed until after the national referendum in December 2023.

Although the government has promoted various reforms to correct inequality as promised, its approval rating fell after the proposed new constitution it backed was rejected in September 2022. It remained low amid rising crime and economic sluggishness, but after the president announced pension and tax reforms, it rose for the first time in June 2023.

Promoting the lithium industry

As we have seen, funding is essential for the government’s various social reforms. The government is therefore focusing on the lithium industry as a new source of revenue. Demand for lithium—used in batteries for electric vehicles and mobile phones—has been rising in recent years, and its importance in the domestic economy is expected to grow.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, South America holds about 60% of the world’s lithium. Chile holds 11.1%, or about 9.6 million tons, trailing Bolivia’s 23.7% and Argentina’s 21.5%. Together the three countries are known as the “Lithium Triangle.”

While Bolivia, which has the world’s largest reserves, has lagged in development due to factors such as a lack of funds and reluctance to allow foreign companies in, production is increasing in Argentina and Chile. As of 2021, Chile was leading other South American lithium holders in production, and globally it ranked second after Australia.

Lithium extraction site at the Salar de Atacama (Photo: Nicolas Nova / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED])

Currently, only Chilean company SQM and U.S. company Albemarle hold extraction rights, and both primarily operate at the Salar de Atacama. Their contracts with the state were signed prior to 1979. After 1979, when lithium was deemed a material used by the nuclear industry, the state did not enter into new extraction contracts with companies in order to secure the resource.

The two companies’ contracts expire in 2030 and 2043, respectively. The government has said it will honor the terms until expiry. At the same time, it plans to establish a new state-owned company and grant it lithium extraction rights. That state lithium company would act as the point of contact for negotiations with private companies and decide whether to partner with them on exploration and development. To realize this, in addition to re-negotiations with the two firms, the plan also needs to secure majority support in Congress, and it has run into difficulties.

These moves have been seen domestically and internationally as a “nationalization” of lithium and have drawn considerable criticism. Boric, however, denies full nationalization, asserting that the new state lithium company will form public–private partnerships with private firms to further develop lithium. He also indicates plans to adopt extraction methods that minimize environmental impacts to support sustainable economic development, and to negotiate with Indigenous communities that hold lithium deposits so they can share in the industry’s benefits.

To prevent profits from flowing out to foreign companies, the government is also considering initiatives beyond extraction and production, such as developing value-added lithium products and establishing lithium-related research institutes. It hopes to form partnerships with private companies for investment and know-how under national policy. In fact, the government has announced that, with investment from a Chinese private company, a plant will be built in Chile to produce lithium iron phosphate, a power source for electric vehicles. However, there are concerns among some companies: if conditions for firms entering public–private partnerships are skewed or overly strict, or if the two existing giants are favored, it could create an unfair playing field for other private companies.

Challenges and outlook

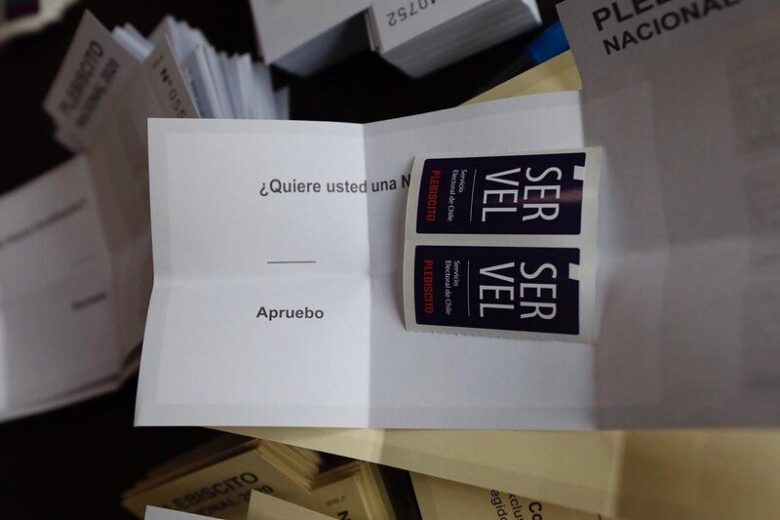

As noted, the new administration has been active both in social reforms and in securing revenue to fund them, but the setback over the new constitution has been a blow to the Boric government that supported its drafting, and has had an impact. Needless to say, the result of the next vote on a new draft could also significantly affect the administration’s efforts.

The 2021 national referendum on the new constitution (Photo: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile / Flickr[CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED])

After the first defeat, the reconstituted constitutional council saw right-wing candidates win a majority of seats, and it is clear the new proposal rolls back significantly in various areas, including abortion rights, marking a retreat. The Boric administration has indicated it will remain neutral regarding the submitted draft.

The public response is cautious, and the chances that the new proposal will be approved at the referendum stage are seen as low. If it is rejected, the current constitution is likely to remain in place, as the Boric administration is not planning a 3rd attempt at reform.

Even if constitutional reform does not occur, there are other approaches to the issues coming to the fore in Chile. As we have seen, the government has sought to improve gender and labor issues through statutory reforms. How will such efforts change the lives of the Chilean people in the future?

Writer: Kanon Arai

0 Comments