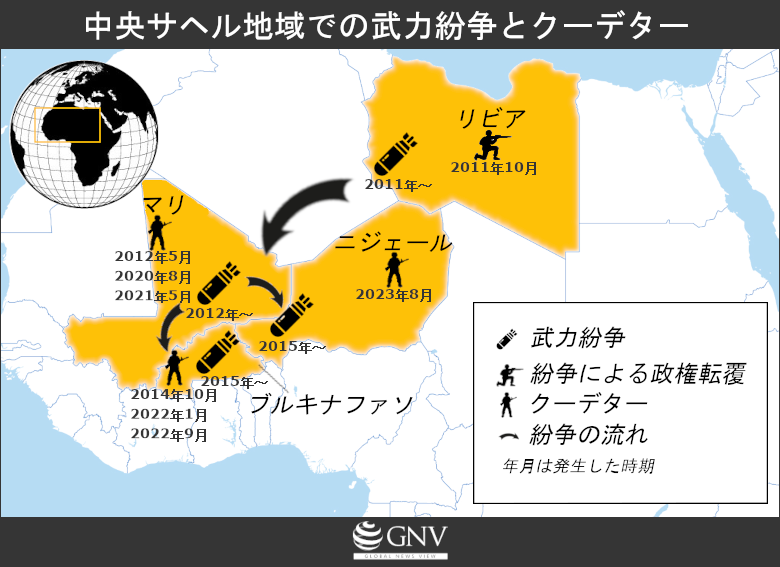

In the first half of 2023, West Africa experienced 1,800 terrorist attacks and nearly 4,600 deaths, and its devastating humanitarian crisis has worsened. Most of these attacks occurred in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Among them, Burkina Faso suffered the most, with 2,725 people killed in terrorism-related incidents between January and June 2023. The Global Terrorism Index calls it one of the “epicenters of terrorism.” It is the most affected country by terrorism on the African continent and the second most affected in the world after Afghanistan.

For decades, the country was called an “island of stability” surrounded by neighbors plagued by conflict and insecurity. However, since 2016, the security situation has deteriorated dramatically, and in 2022 there were two military coups. What in Burkina Faso has led to this worsening security? Are there long-standing issues that contributed to the rise in violence in the country? Could the current situation have been avoided if these issues had been addressed? What future awaits Burkina Faso? To answer these questions, this article traces the country’s history, examines present challenges, and finally explores directions toward a brighter future for Burkina Faso.

Monument to the Martyrs in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso (Photo: Francais / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

History of Burkina Faso

From the 11th to the 19th centuries, the Upper Volta basin, which corresponds to the territory of present-day Burkina Faso, was mainly dominated by the Mossi people. The Mossi were a cavalry people and established kingdoms primarily in the central part of the current territory. The Mossi realm was divided into five autonomous and independent kingdoms—Wagadugu, Tenkodogo, Fada N’Gourma, Yatenga, and Boussouma. These kingdoms had stable administrative structures but were never unified. Eventually, from 1328 to 1477, the Kingdom of Yatenga rose as a major force attacking the neighboring Songhai Empire, occupying Timbuktu and raiding the trading posts of Macina.

Through local nomadic merchants and Arab traders, Islam gradually spread throughout the kingdoms by peaceful means. The slave trade penetrated the region, but the Mossi kingdoms were able to resist Arab and European slave trades and raids until the 1800s. They also established external trade relations with other African polities such as the Fulani kingdoms and the Mali Empire, which had already adopted Islam. In 1896, the Mossi kingdoms were conquered by France by brutal methods including mass killings. France then created the colony of Upper Volta from several kingdoms including the Mossi, following agreements with its then-rival Britain, and drew borders that reflected French designs rather than cultural differences among ethnic groups or the frontiers of former kingdoms.

In 1919, the colony of French Upper Volta was incorporated into French West Africa, a federation established by merging several provinces of Côte d’Ivoire. France regarded the lands of the Mossi kingdoms and the entire Upper Volta region as a source of labor for various projects in other territories; many Voltaics were sent to work in Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), and Côte d’Ivoire. Each colony was assigned two to four goods to export to France, and the colonies were sustained through coercion such as head taxes and forced labor, centered on the coastal cash-crop zones and migrant labor. As a result, in the French colonies, everyone except children, the elderly, and people with disabilities had to pay a head tax and perform forced labor, and many Voltaics were compelled to migrate to the coast to earn money to pay taxes to France.

This exploitative labor regime eventually clashed with the needs of the rural economy, undermining food-crop production and causing famine in Upper Volta and Niger by 1931. In 1932, in response to people fleeing colonial rule into the British Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), the colonial administration divided the territory among other colonies. After World War II, many resumed the push for territorial self-government, and in 1947 Upper Volta was revived.

In 1956, reorganization of France’s overseas territories began, and the new measures approved by the French Parliament in 1957 granted considerable autonomy to each territory. In 1958, the Republic of Upper Volta became an autonomous republic within the French Community. Thereafter, in 1960, the Republic of Upper Volta became independent.

Post-independence politics

The Constitution of Upper Volta enacted in 1960 after independence provided for presidential and National Assembly elections, and Maurice Yaméogo was elected the first president. However, a coup took place in 1966, and the Yaméogo administration was overthrown, mainly due to corruption and economic problems. In the following years, the country saw repeated changes of government and instability. In 1983, a group led by military officer Thomas Sankara launched a coup, and he subsequently took control of the state.

In 1983, Sankara established the National Council of the Revolution (CNR) and the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), mobilizing the masses to carry out the CNR’s revolutionary program. This occurred as the people of Upper Volta were facing, among other things, rapid urbanization, limited access to farmland, communicable diseases due to poor sanitation, restricted access to health care and education, the marginalization of women, and famine. Many of these problems stemmed not only from shortcomings in governance but also from the enduring legacy of French colonial rule and France’s post-independence influence.

Sankara worked to curb public spending, fight corruption within the government, and reduce external influence and exploitation. Cotton was a major cash crop for the country’s farmers, but the French state-run Compagnie française pour le développement des fibres textiles (CFDT) stood squarely in the way. Sankara called on Africans, especially his own citizens, to control their own resources. For example, he encouraged local processing of cotton for the production of traditional clothing known as “Faso Dan Fani.” In other words, from the perspective of benefiting local cotton farmers and improving the national economy, he promoted wearing locally made clothes and required civil servants to do so.

During his presidency, many other bold changes and major achievements were realized, including reductions in infant mortality, improvements in literacy and school enrollment, and the elevation of women’s status in government. His administration sought to ensure that all citizens had at least two meals a day and access to safe drinking water. To address environmental issues, Sankara launched large-scale reforestation. As a result, Upper Volta achieved food self-sufficiency and cut off aid mainly from France. He believed that French aid was a system that sustained dependence rather than helping the country.

On the first anniversary of his regime, he changed the country’s name from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which in the local Mossi and Dyula languages means the “land of upright people.” However, Sankara faced domestic and foreign resistance and divergence from public opinion, and tensions rose over the government’s repressive policies and overall direction. In 1987, he was assassinated in a coup, and his former military comrade Blaise Compaoré took power.

Thomas Sankara (left) and the entrance to his memorial (right) (Left: Photo: Unknown, Burkina Faso Government / Wikimedia Commons [fair use] ) (Right: Photo: Lamin Traore(VOA) / Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

The new government then formed the Popular Front (FP) and pledged to continue and pursue the goals of the revolution. However, the revolutionary program was soon abandoned and the pre-revolutionary system resumed. Under Compaoré’s rule, many political crimes became routine, and pressure and bribery against opponents and critics enabled the government to survive. Many courageous people who refused to accept bribes and resisted government pressure were killed. One of them was investigative journalist Norbert Zongo. He was investigating political, economic, and social scandals, including the death of the president’s driver’s brother, when in 1998 his car was found burned out, with two colleagues and his brother inside.

After this incident, a strong public backlash led to the establishment of a Council of the Wise, which ultimately recommended reinstating presidential term limits, which the regime had abolished in 1997. The 2000 constitutional amendment restored presidential term limits. However, no one was punished for Zongo’s murder, and impunity for crimes was normalized as one manifestation of corruption under the regime. In the 2010s, the monopoly of power by President Compaoré and his entourage—combined with corruption, misgovernance, and impunity—plunged many into poverty and widened inequality in Burkina Faso. Amid this, President Compaoré sought to hold a referendum to abolish presidential term limits again, which sparked fierce popular resistance. In response, in October 2014, Compaoré resigned and fled to Côte d’Ivoire.

The following month, a transitional government was formed under the condition that elections be held within a year. President Michel Kafando’s statement that “nothing will be the same again” (Plus rien ne sera comme avant) carried great significance for the people of Burkina Faso, raising hopes for justice and political improvement. After the transition, the government first moved to dissolve the Regiment of Presidential Security (RSP), which had been a tool of repression under the Compaoré regime. The RSP had a long history of involvement in political violence and assassinations, including the murder of Zongo. After being notified of its dissolution, the RSP launched a coup in September 2015, but it failed, which consolidated the position of the new government, and presidential elections were held in November.

The winner of that election was Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, who had previously served as prime minister and speaker of parliament under Compaoré. However, most of the central figures in the new administration, including Kaboré, had been involved in the former Compaoré regime, making Kafando’s earlier statement come to nothing. The new president faced numerous challenges—chief among them the conflict that spilled over from neighboring Mali into Burkina Faso starting in 2015. Terrorist attacks were frequent in the north and spread across the country.

Militants in northern Burkina Faso (Photo: aharan_kotogo / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

A spreading insurgency

The conflict that began in Mali and expanded into Burkina Faso can be traced back to northern Mali, where the Tuareg historically account for much of the population. The Tuareg have lived in and around the Sahara for thousands of years, with the majority residing in Mali. Since Mali’s independence from France in 1960, the northern region inhabited by the Tuareg has been left behind in development. With the government failing to pursue comprehensive development in the north, four rebellions have occurred since the 1960s. In 1982, Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddafi declared Libya the homeland of all Tuareg, recruiting many into his army, while others found jobs in Libya.

In 2011, after Gaddafi’s regime fell during the so-called Arab Spring, Tuareg soldiers returned to Mali with advanced weapons. Confronted with poverty, drought, and disease at home, they formed the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) to fight for autonomy and development of the region. The MNLA quickly seized control of northern Mali and declared the independent state of Azawad. However, conflicting ambitions among Tuareg communities and the emergence of new armed groups such as Ansar Dine (an Al-Qaeda affiliate) thwarted the MNLA’s designs for Azawad. Azawad did not last; with military intervention by France and others, the Malian government recaptured the territory, and the conflict shifted into a guerrilla war. As a result, the situation in Mali remains unstable, with ongoing conflict between multiple groups and the Malian armed forces.

In 2012, the government of Burkina Faso was already concerned about the potential spread of instability from Mali and sought talks between Mali’s then-interim President Dioncounda Traoré and armed groups in the north. President Compaoré of Burkina Faso met both the secular Tuareg separatist MNLA and the Al-Qaeda-linked Ansar Dine to seek a peaceful resolution to the conflict. The initial contacts were intended to determine the practical details for eventual negotiations. During Compaoré’s time, there were also suspicions of collusion with Islamist extremists, and persistent rumors that this was why the country was spared attacks. After the fall of the Compaoré regime in 2014, the MNLA and Islamist groups lost support, and the latter turned their attention to Burkina Faso and launched attacks. These attacks then spread to Niger as well.

Woman transporting cotton (Photo: CIFOR / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Current challenges

The rise of violent extremism in Burkina Faso is driven by a complex interplay of factors, including the end of the Compaoré regime, persistent poverty, entrenched corruption and misgovernance, and state injustice. As of 2018, an estimated 83% of the population lived below the Ethical Poverty Line (※1), according to estimates. People in rural areas in particular have long faced difficulties accessing public services and justice.

In 2019, long-standing social injustices and exclusionary policies—especially in rural areas of Soum Province in the north—led to the recruitment of fighters among Fulani pastoralists. With insufficient government response, many local self-defense forces emerged, further complicating the security situation. From 2018 to 2019 alone, Burkina Faso recorded a 127% increase in terrorist attacks and a staggering 587% increase in total deaths, according to records. What began as a conflict between Islamist extremists and the state has now shifted into conflict between local communities. Inefficient political management, state abuses against civilians and the impunity for those crimes, a lack of employment opportunities, and extreme poverty are powerful incentives used by extremist groups to draw local residents into the conflict.

As a result of the conflict, armed groups affiliated with Al-Qaeda and IS (Islamic State) have occupied large swaths of Burkina Faso’s territory, and millions have been displaced. This has occurred while French troops were stationed in Burkina Faso.

After that, in January 2022 Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba toppled the Kaboré government, and in September of the same year Captain Ibrahim Traoré ousted Damiba and became transitional president. Traoré’s transitional government aims to hold democratic elections in July 2024.

One month after the September 2022 coup, Traoré pledged to fight extremist forces, sought support from countries including Russia, and emphasized the need for troop training and intelligence.

However, the transitional government’s expectations were thwarted. In stark contrast to the massive military aid provided to Ukraine, Western countries refused to sell weapons for Burkina Faso’s conflict. This is seen as one reason Burkina Faso has expanded relations with non-Western partners including China, Iran, Turkey, North Korea, and Venezuela.

In addition to diversifying partners, in October 2022 the transitional government launched a campaign to recruit 50,000 civilians into a volunteer defense force known as the Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland (VDP). The new administration declared that only Burkinabè should fight for national security, and due to the country’s economic difficulties, President Traoré announced that he would not take the usual presidential salary. He also in January 2023 launched the Patriotic Support Fund, enabling Burkinabè and others to financially support the defense of Burkina Faso.

However, these measures have led to a steady deterioration in diplomatic relations with France. In 2023, Burkina Faso requested the French ambassador’s departure and subsequently announced the termination of the military accord that had allowed French forces to fight insurgents within its borders.

President Ibrahim Traoré (Photo: Lamin Traore(VOA) / Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

The path to a solution

Burkina Faso continues to suffer greatly as a result of the armed conflict, and so do its neighbors. Mali and Niger have followed the same trajectory, and even countries south of Burkina Faso’s borders have seen attacks.

It is therefore clear that discussions and actions toward resolving the violence and instability must be regional and comprehensive. Thus far, military solutions—both domestic actions and foreign interventions—have been ineffective or even counterproductive, with violence breeding more violence. One study found that 71% of those who join extremist groups cite government actions—such as the killing or arrest of family or friends—as the trigger.

Most importantly, however, these countries must address the social problems they face. Poverty, unemployment, and social inequality are major factors that created and expanded the conditions for conflict, and the conflict in turn has worsened them. It has displaced millions and destroyed the lives of many more. Humanitarian aid is an essential component, but improvements in governance by national governments and in the policies of foreign countries are also indispensable. Building governments that respond to citizens’ needs—and, at the international level, reforming political and trade systems so they do not simply reflect the interests of wealthy countries—will greatly contribute to resolving this conflict.

※1 GNV adopts an Ethical Poverty Line of US$7.4 per day rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line as of 2021 (US$1.9 per day). For details, see the GNV article “How should we interpret the world’s poverty situation?”

Writer: Gaius Ilboudo

Translation: Yudai Sekiguchi

Graphics: Ayaka Takeuchi

What an enjoyable article! I just read this and really love it. For more related blogs please see iplt. Thanks!

In der heutigen schnelllebigen Welt suchen viele nach Möglichkeiten, die Notwendigkeiten des Lebens zu vereinfachen. Kontaktieren Sie uns jetzt, um einen Führerschein zu kaufen. Wenn Sie eine schnelle und effiziente Lösung benötigen, ziehen Sie die Möglichkeit in Betracht, Ihren Führerschein online zu kaufen. Diese Methode bietet beispiellosen Komfort. Wenn Sie einen Führerschein kaufen, sparen Sie wertvolle Zeit und vermeiden bürokratischen Papierkram. Darüber hinaus stellt ein legaler Kauf eines Führerscheins sicher, dass Sie die Vorschriften einhalten, und gibt Ihnen Seelenfrieden. Für diejenigen, die es eilig haben, ist der schnelle Erwerb eines Führerscheins die optimale Wahl. Bestellen Sie einfach einen Führerschein und erleben Sie, wie einfach es ist, einen Führerschein zum Verkauf immer zur Hand zu haben. Nutzen Sie diese moderne Lösung noch heute.