Colombia has been in armed conflict since the 1960s. Amid this, in June 2023 the government and an armed group called the National Liberation Army (ELN) reportedly reached a ceasefire agreement. The person who achieved this was President Gustavo・Francisco・Petro・Urrego (hereafter, Petro), who took office on August 7, 2022. In addition to attempts to resolve the conflict, he has submitted several reform bills to Congress to correct the poverty and inequality that are among the causes of the conflict, and he is confronting serious environmental issues such as the destruction of tropical rainforests, proposing remedies. The Petro administration has thus undertaken numerous bold reforms from the outset of its tenure. Let’s look at what each reform entails and what the outlook is.

President Petro at the inauguration ceremony (Photo: Raul Ruiz-Paredes / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Colombia’s challenges and their background

First, we trace the historical background of internal discord in Colombia. In what is now Colombian territory, multiple ethnic groups lived primarily through agriculture while also trading with other settlements. However, when Spanish colonial rule began in the 16th century, the region came under the strong, arbitrary influence of Spain. On its vast and fertile lands, plantations were established and sugar and tobacco for export were produced. Behind this production was the dominance of settler landholding, including systems that forced Indigenous people to labor on the lands where they lived (the encomienda system). Viceroys sent by the Spanish government to administer the land allowed this in exchange for the wealth settlers delivered to them.

Colombia became independent from Spain in 1810, but thereafter it began to be strongly influenced by the United States. At independence, what are now Panama and Venezuela were also part of Colombia, but in 1830, beginning with Venezuela’s separation due to internal division, its territory shrank. In 1903, Panama became independent from Colombia, against a backdrop of the United States’ interest in the development profits of the Panama Canal. American fruit companies also began building plantations in Colombia, where local workers were subjected to harsh conditions such as low wages and long hours. Unable to endure not only land ownership inequality but also poor labor conditions and the resulting poverty and exploitation, people went on strike in 1928 at a banana plantation run by a U.S. company. Under U.S. pressure, the Colombian military, prioritizing the company’s interests, opened fire on people gathered during the strike, causing many casualties. This event at the banana plantation later came to be known as the Banana Massacre.

Thereafter, inequality in land ownership between a small economic elite and farmers, and the poverty and disparity arising from it, did not improve. In rural areas where this problem was especially severe, agricultural communities were formed to confront this inequality and protect farmers; influenced by the 1950s Cuban Revolution, farmers and workers seeking further land rights founded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 1964. However, the state and large landowners, viewing this as a threat, decided to deploy the military to dismantle it, and a violent conflict began with those who resisted. The ELN was also an armed organization founded in 1964 with the aim of resisting unequal distribution of land and resources, carrying out attacks on large landowners and infrastructure companies. As fighting between government forces and armed groups continued, multiple paramilitary groups allied with the government emerged, causing many casualties.

Furthermore, the drug problem that worsened from the 1980s intensified the conflict. Massive drug organizations emerged that illegally produced cocaine in areas beyond the government’s oversight, cooperating not only with FARC and the ELN but also with pro-government paramilitaries. Cocaine was smuggled mainly to Europe and the United States, where demand was high and prices were elevated, bringing enormous profits to drug and armed organizations. Under the banner of eradicating drug cartels, the United States has provided considerable military aid to the Colombian government.

Amid this, former President Juan Manuel Santos, who took office in 2010, sought to resolve the conflict and began peace negotiations with FARC in 2012. They reached a peace agreement in 2016, but domestic opposition grew, arguing that the content conceded too much to FARC, and it was initially rejected. After revisions, the peace agreement formally took effect, marking a major step toward peace. However, some members within FARC opposed it and split, and breakaway groups such as the FARC Estado Mayor Central (EMC) remained. The agreement also included land reform to transfer unused farmland to landless farmers, but this has made little progress. There is also the reality that in former FARC-controlled areas that were demobilized under the agreement, new drug-related criminal organizations have expanded their influence.

The government and the ELN also achieved a bilateral temporary ceasefire from October 1, 2017 to January 9, 2018. However, while seeking a political resolution to the conflict, violent acts by the ELN continued after the ceasefire, and in January 2019 the government side suspended the peace talks.

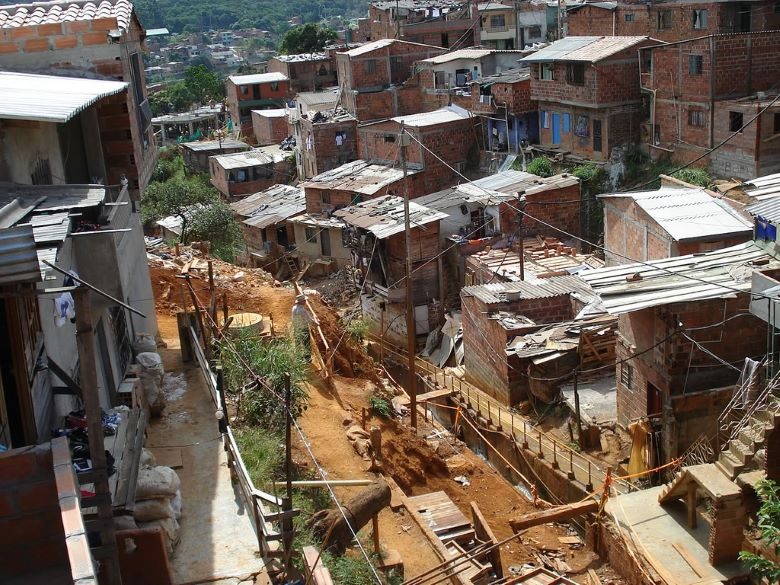

Cityscape of Medellín in northern Colombia (Photo: Luis Perez / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA2.0])

Next, we look at Colombia’s economic situation as conflict continues across the country. According to the World Bank, as of 2021, the proportion of people in Colombia living on $7.5 a day or less is 43.4% (※1). Inequality in land ownership has not improved even in the 21st century, with 1% of large landowners owning half of the farmland, a structure in which a small number control vast tracts of land remaining intact. The long-running conservative right-wing governments, which have favored economic elites such as landowners and incoming U.S. economic elites, continue to have a serious impact today. There has also been financial collusion between right-wing governments and these elites, and corruption and political decay persisted.

The coal and oil industries that have flourished since the 1980s are also deeply tied to Colombia’s economy. The country is economically dependent on oil, which accounts for 49.1% of exports. Coal production is also abundant, making it the second-largest export item after oil. From his 2010 inauguration, former President Santos sought to attract foreign capital to boost exploration and development, and former President Iván Duque, who took office in 2018, also promoted the oil and gas industry and raised production, meaning that successive governments have supported the sector. However, behind the development of the oil and coal industries, deforestation has progressed, with about 6 million hectares of forest lost over the 25 years from 1990 to 2015. Colombia boasts rich biodiversity, but this ecosystem is threatened by the decline of forests.

The emergence of the Petro administration

As we have seen, Colombia was long governed by consecutive right-wing administrations, under which the inequality and disparity in which a small ruling class held most of the land and resources were not corrected. As public dissatisfaction with this grew, attention in the 2022 election focused on the left-wing candidate, Petro.

Petro himself has a past of belonging to a group called the April 19 Movement (M19), a leftist guerrilla organization. M19 was founded by intellectuals such as scholars and doctors and operated mainly in urban areas. As a member, he was captured by the military in 1985 but later released, and he participated in peace talks that in 1990 led to the disarmament of M19 and opened the way for the formation of a left-wing political party. His political career began from there; he served as a member of Congress and mayor of the capital Bogotá, and repeatedly ran for president. The small ruling class that opposed Petro showed reluctance toward the bold social reforms he advocated, and for many years he failed to be elected.

In 2022, when Petro again ran for president, he faced strong resistance from some quarters. However, the policies he presented—pursuing comprehensive peace to resolve the conflict and tackling social reforms to correct the inequality and poverty underlying the conflict—raised voter expectations. As a result, he was elected in June 2022. After taking office in August of the same year, an obstacle to initiating reforms was that the seats held by his Historic Pact coalition (The Historic Pact coalition) did not constitute a majority. He reached out to centrist and conservative parties and formed a coalition government.

Another plan he has in mind is a policy of reducing oil and coal in order to address both domestic environmental issues like deforestation and global environmental issues such as climate change. The policies below outline these efforts.

Toward “Total Peace”

Petro proposed a “Total Peace” plan (※2) aimed at ending the conflict and achieving peace at home. He is seeking to actively create spaces for dialogue with armed groups still active in the country. As noted at the outset, this movement led to a ceasefire agreement with the ELN. Since the initial round of talks in November 2022, and despite tensions from differences in positions, repeated consultations resulted in a six-month ceasefire between the two sides. The government is also actively pursuing peace talks with other armed groups such as the EMC, and stated that in February 2023 it reached an informal ceasefire with four armed groups including the EMC.

Smuggled cocaine (Photo: Coast Guard News / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Measures are also being taken to address the drug problem, which has been closely linked to the conflict. Until now, the Colombian government, with U.S. military assistance, has fought drug organizations through the armed forces. However, the area under coca cultivation—the main ingredient of cocaine—increased by 43% in 2021, showing that enforcement through force has not been effective. In response, President Petro has devised a plan to shift farmers from illegal coca cultivation to sustainable, legal crops, and is already expanding land access to support this. However, since no crop currently offers higher returns than coca, it is unclear whether the plan can succeed. Petro also ultimately aims to legalize the production and trade of coca and cocaine. By having the government regulate the cocaine market, the goal is to eliminate illegal transactions and reduce the profitability of the drug trade.

Beyond the armed conflict, there has also been progress in diplomacy. The restoration of diplomatic relations with neighboring Venezuela, with which ties had not been very good, was a major development following Petro’s inauguration. Regarding the ELN, which operates in both Colombia and Venezuela, the Venezuelan government cooperated with Colombia’s proposal to hold peace talks. This served as a stepping stone to conflict resolution, including hosting the first round of talks with the ELN in Venezuela. Conversely, there were concerns this could strain relations with the United States, which does not recognize Venezuela’s current government. However, when President Petro visited the U.S. in April 2023, talks with the U.S. president were constructive, and there were no major differences in their views.

Alleviating poverty and inequality

In addressing this problem—which is also at the root of the conflict—the Petro administration is attempting various approaches through redistribution of wealth and resources, reducing poverty, and guaranteeing a minimum standard of living. Here we follow the reforms and bills in the areas of taxation, labor, pensions, and health.

The first is tax reform. In addition to the tax increases on high-income earners that he had signaled during the campaign, a bill imposing a windfall profits tax mainly on extractive industries such as coal and oil was passed just two and a half months after Petro took office. A major background factor in this success was Petro’s formation of a coalition government with a majority in Congress. As a result, tax revenues have increased, and there are signs of an improving fiscal deficit.

The second is improving working conditions. In May 2023, the government submitted to Congress a bill to shorten working hours and raise overtime pay. The aim is to eliminate the exploitation of workers and establish fair and equitable working conditions through this reform. Critics argue that the measures will hinder job creation, but the administration believes the reform will also help reduce poverty and stabilize people’s lives, and intends to proceed.

A worker at a coffee farm in Colombia (Photo: CIAT / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

The third is pension reform. The government states that only one in four people meets the conditions to receive a pension. To provide more people the opportunity to receive pensions, in May 2023 it submitted to Congress a bill to expand the pension system itself. While there are concerns about the impact on government financing, President Petro seeks to establish a relationship in which the state guarantees the rights of its citizens.

The fourth is improving the health care system. The aim is to increase nationwide access to health care, provide funding to facilities that deliver medical services, and raise the salaries of medical workers. The government also considered abolishing the existing private health care network known as the EPS, and having municipal and state employees take over its role. The EPS are private health insurance providers that give enrolled people access to care and partially cover medical costs. In recent years, however, their finances have deteriorated, leading to delays in providing care to people and in payments to medical institutions. Yet there was criticism that having government agencies assume the role played by the EPS would politicize health care and foster corruption. The Petro administration withdrew the elimination of the EPS, but has proposed provisions that limit some functions, such as centralizing payments to medical institutions. Since this reform, parties in the coalition have begun to break away.

Transition to a green economy

President Petro argues that the extraction of coal and oil, pillars of the national economy, is responsible not only for deforestation within Colombia but also for the increase in global carbon dioxide emissions and climate change, and he wants to reduce them. As part of this, the government has announced it will not issue new permits for fossil fuel exploration. Explorations already approved can continue until completion. Currently, crude oil production that had increased at the end of 2022 has declined since 2023, and some coal mines have closed.

A scene at a coal mine site in Colombia (Photo: Hour.Poing / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

There are criticisms that this bold reform amounts to “economic suicide.” Because coal and oil are major export items, cutting them is certain to damage the economic situation. The government plans to offset this by promoting agriculture and tourism and by reducing fossil fuels in stages, but because the outlook is unclear, investment has declined.

On the other hand, in terms of domestic electricity supply, the share of thermal power using fossil fuels is small, and since hydropower accounts for 64.9% of domestic electricity, this goal is easier to achieve compared to the issues described above. Efforts are underway to complement this by developing other renewable energy sources and increasing the share of wind and solar power.

Outlook

As we have seen in this article, reforms within Colombia appear to be progressing. But the path is not necessarily easy. There has been a corruption scandal, and Petro’s approval rating, which was 48% at the start of his term, had fallen to 30% nine months later—several points lower than the approval ratings recorded by past right-wing governments, according to results. Since the period when health care reform was being pushed, the parties forming the coalition have increasingly drifted away due to disagreements over direction.

Although the more President Petro tries to hurry reforms, the more new problems arise, such as growing rifts with those around him, the Petro administration—which has advanced reforms this far in about a year since its inauguration—will likely continue to warrant attention.

※1 GNV adopts the ethical poverty line ($7.4 per day) rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line as of 2021 ($1.9 per day). Here, due to data constraints, 7.5 is used instead of 7.4. For details, see GNV’s article “How should we interpret global poverty?”

※2 A peace plan consisting of five pillars: implementing substantive land reform as included in the peace agreement with FARC; resuming peace negotiations with the ELN; implementing peace agreements with FARC breakaway groups; proactive dialogue with the country’s small elite; and investment in peace-related education.

Writer: Kanon Arai

Graphics: Misaki Nakayama

潜んだ世界の10大ニュースでペトロ大統領について一部取り上げられていましたが、今回詳しく知れてよかったです。

これまでの歴史から継承されてきたことから脱却するためには、相当な決断力と行動力を要することが、この記事から理解できました。

ペトロ政権下で、税制改革や労働環境の改善などの改革がなされたようですが、これは、トップのすぐ下にいる官僚たちの協力もなければできないことだと思います。その点でも、昔から何か大きな変化はあったのでしょうか?

薬物って、なんでこんなに高く売れてしまうんでしょうかね、、、。

モノカルチャー経済ってよく言いますけど、稼ぎ口を複数確保しておくことって、国家の維持にとても重要な様さなんだなあと思いました。

左派政権というと独裁に突き進んでいくことが多いイメージでしたが、実現可能性は別として国の根本的な問題を解決しようと取り組んでおり、イメージが変わった。また、左派とアメリカは仲が悪いイメージでしたが、うまくやっていけている?のが意外でした。

ペトロの改革が成功したら、中米の希望になれそう。アメリカに洗脳されずに頑張って欲しい