On 2023-2–6, the Turkey-Syria earthquake struck. In total, more than 35,000 people lost their lives in Turkey and Syria. The earthquake has also been reported to have triggered a serious humanitarian crisis. However, Syria had in fact been experiencing the worst humanitarian crisis in its history even before the earthquake occurred.

About 1 year before the earthquake, in January 2022, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) warned that Syria was facing its worst-ever humanitarian crisis. According to the United Nations, by the end of 2022, about 14.6 million people in Syria needed humanitarian assistance. Around 6.6 million Syrians had taken refuge abroad, and approximately 6.7 million people were internally displaced. With the impact of the recent earthquake, there are concerns that the humanitarian crisis will deteriorate even further.

Why does the humanitarian situation in Syria continue to worsen? In this article, we unravel Syria’s humanitarian crisis by looking at the trajectory of the conflict that has continued since 2011 and the actions of various countries surrounding the conflict.

A view of a refugee camp in Idlib Governorate, northwestern Syria (Photo: Ahmed akacha / Pexels [Legal Simplicity])

目次

History of Syria

Syria is a Middle Eastern country of 185,000 square kilometers with a population of about 21.56 million, home to people with diverse cultural, linguistic, and ethnic backgrounds, including Arabs, Kurds, and Armenians. In terms of population share, roughly 75% are of Arab origin, about 15% are of Kurdish origin (Note 1), and about 15% are of Armenian or other origins. Looking at religion, about 87% of the population is Muslim, of whom roughly 74% are Sunni and about 13% are Shi’a or followers of the Alawite branch.

Let us briefly review Syria’s history. The region was once under the control of the Roman Empire, and in the 7th century it came under the rule of the Islamic empires. Over time, the Islamic empires that governed the Syrian region changed, and in the 16th century it came under Ottoman rule. Syria remained part of the Ottoman Empire until, after the Ottoman defeat in World War I, in 1920 it became a French colony under the Sykes–Picot Agreement. In that agreement, the Middle East was partitioned by Britain, France, and Russia without regard to local circumstances. After World War II, the drive for independence intensified, and in 1946, Syria became independent as the Syrian Republic.

After independence, successive rebellions and coups left domestic politics unstable. The Syrian government at the time, espousing Pan-Arabism (Note 2), sought union with Egypt, and in 1958 it merged with Egypt to form the United Arab Republic. However, Egyptian dominance in the union fueled Syrian resentment, and in 1961, Syria reestablished itself as the Syrian Arab Republic.

The Ba’ath Party then took power in the newly re-independent Syria. The Ba’ath Party descends from the Ba’athist movement, originally born in Iraq and advocating Pan-Arabism, and it remains in power in Syria today. The figure who consolidated the Ba’ath Party’s rule was President Hafez al-Assad (hereafter, H. Assad), who took office in 1971. A former military officer, H. Assad advanced authoritarian policies in coordination with the Ba’ath Party, the military, and Alawite bureaucrats. As his policies—including economic and land reforms, promotion of education, and strengthening of the military—produced certain results, the Ba’ath Party gained some popular support and domestic politics stabilized.

A photograph of the Assad father and son displayed in an apartment room (Photo: Stijn Nieuwendijk / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Although the Ba’ath Party secured a measure of domestic support, anti-Ba’ath forces also existed within Syria. The Ba’ath Party’s leadership—including H. Assad—was dominated by the Alawite branch of Shi’a Islam, concentrating power through authoritarian rule. Given that Sunnis are the majority in Syria, many opposed Alawite authoritarian control. The Ba’ath Party is also known for its brutal military suppression of such opposition forces. Notably, in 1982, the Syrian military, under orders from H. Assad, massacred between 5,000 and 10,000 civilians who opposed the Ba’athist regime. In addition to harsh repression, H. Assad implemented information and speech control to maintain and strengthen his dictatorship.

The Syrian government also has a history of participating in Arab–Israeli wars. In the 1967 Six-Day War, Syria was defeated by Israel and lost the Golan Heights, and the antagonism with Israel continues to this day.

Outbreak of the conflict

In 2000, upon the death of H. Assad, his son Bashar al-Assad (hereafter, B. Assad) became president. At first, B. Assad signaled openness to the pro-democracy civic movement known as the “Damascus Spring”, pledging liberalizing policies such as expanding civic participation and easing information controls. However, perhaps due to opposition from conservatives who had benefited under H. Assad, these policies gradually shifted, and he ultimately took a more entrenched authoritarian stance. Specifically, under B. Assad, information was censored and arrests and torture of dissenters were frequently reported.

President Bashar al-Assad (Photo: Пресс-служба Президента России / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 4.0])

Repression of Kurds in Syria also became a major issue. Kurds living across Turkey, Iraq, and Syria who sought independence in each area became targets of repression for B. Assad. In fact, under B. Assad, Kurds in Syria were denied rights such as learning Kurdish in schools and celebrating traditional Kurdish festivals, apparently to suppress Kurdish identity. After large-scale protests by Kurds erupted in 2004 following years of pent-up grievances, repression intensified.

Let us now trace the historical development of the Syrian conflict. The spark was the “Arab Spring”, a wave of mass pro-democracy movements primarily in North Africa and the Middle East from 2010 to 2012. In 2011, its influence reached Syria, where 15 boys who had scrawled anti-government graffiti were detained and tortured—a widely reported incident. In response, opposition supporters long dissatisfied with restrictions on their rights launched protests across the country. The Syrian government not only arrested and imprisoned many participants, but also killed hundreds of demonstrators. Facing this heavy-handed response, opposition groups rose up throughout Syria, plunging the country into conflict.

In July 2011, military defectors formed the anti-government armed group Free Syrian Army and claimed leadership of the opposition, but many local groups refused to recognize its authority, and the conflict spread as hundreds of groups fought the Syrian military independently. In August 2011, some opposition forces came together to form the Syrian National Council, but it failed to function as a unifying body. In 2012, a U.S.-led opposition meeting resulted in the formation of the Syrian National Coalition. The coalition had 60 members, 22 of whom were from the Syrian National Council, but it too has been unable to unify the opposition.

A mosque destroyed by the conflict (Photo: Christiaan Triebert / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

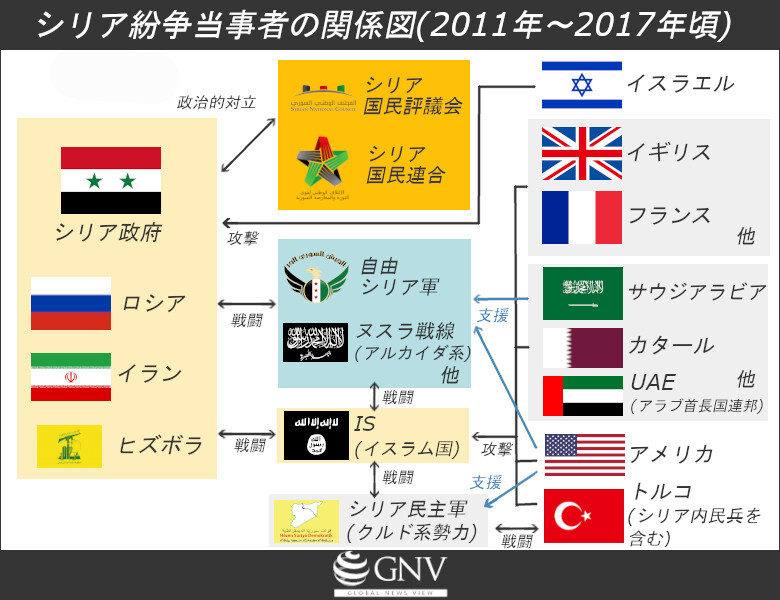

One reason organizations like the Syrian National Coalition could not unite the opposition was the involvement of foreign sponsors. The United States and other Western and Middle Eastern countries each supported different opposition groups to expand their own influence, creating tangled flows of aid and preventing the emergence of a unifying body. In addition, within the opposition, extremist Sunni groups formed, revealing fundamental ideological divides. Although opposition groups shared the goal of toppling the Ba’athist regime, their ideologies varied widely, making unity difficult.

After the conflict began, Kurdish organizations also accelerated their activities as opposition forces, aiming for autonomy within Syria. The PYD (Democratic Union Party), a group linked to Turkey-based PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), was active in Syria and pushed for autonomy after the conflict broke out. In 2012, as B. Assad’s forces withdrew from Kurdish-populated areas, the PYD took control of those areas and has effectively governed them since.

Two years into the conflict, in 2013, as all sides were exhausted by the prolonged fighting, extremist groups gained ground. The Nusra Front, an al-Qaeda (Note 4)-affiliated extremist group formed in 2012, fought against government forces alongside other opposition groups. At the same time, it targeted many other factions in the country, including Kurdish forces.

From 2014 onward, the IS (Islamic State) had a major impact on the conflict. Originally a Sunni extremist organization active in Iraq, IS expanded into Syria in 2014 and controlled extensive areas in the north and east. The United States initially watched the group’s rise, seeing it as potentially contributing to the fall of the B. Assad regime. However, as IS’s extreme propaganda grew, the U.S. came to view it as dangerous, formed a coalition with Arab and European countries, and launched large-scale airstrikes targeting IS. From 2015, Russia also carried out airstrikes against IS as part of its support for B. Assad.

A YPG (People’s Protection Units) fighter (Photo: Kurdishstruggle / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

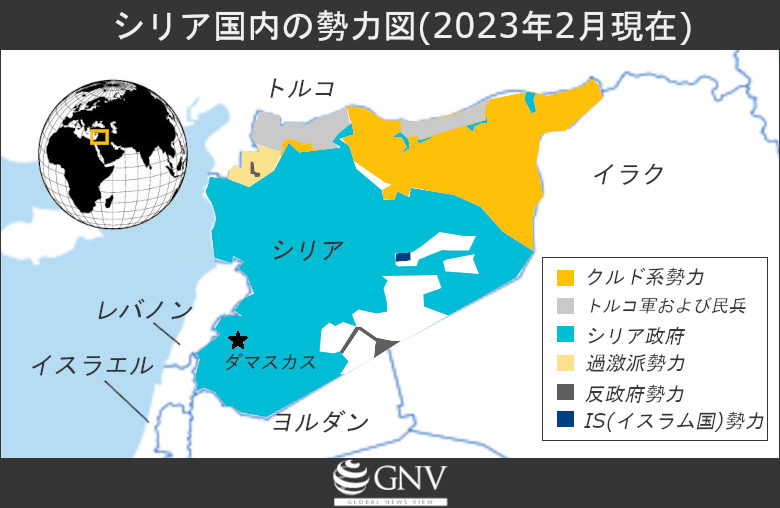

Kurdish organizations were also key in combating IS. They took on IS because the group threatened to advance into areas governed by Kurdish communities. In 2015, the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces), led primarily by the YPG (the PYD’s military wing), was formed to counter IS. The SDF, backed by the United States, fought fierce battles against IS. After IS was driven out, the YPG expanded its previously held autonomous areas and now effectively controls a wide swath of eastern, northern, and northeastern Syria.

Having steadily lost territory under these attacks, IS had lost nearly all its holdings by late 2017. During this campaign, Russia, which was conducting airstrikes against IS, also backed the Syrian government by striking opposition groups. As a result, government forces went on the offensive and regained control over most of the country. Currently, the opposition holds only Idlib Governorate and areas under Kurdish administration.

Countries surrounding the conflict

The Syrian conflict, which has drawn in numerous domestic actors and continues to this day, is also closely intertwined with foreign actors. Here we look at the countries and forces supporting the Syrian government and the opposition, and their trajectories around the conflict.

First, Iran is a major supporter of the Syrian government. By 2022, Iran had reportedly provided billions of U.S. dollars in support. It has also trained and funded the Shi’a armed group Hezbollah (Note 5) based in Lebanon, deploying it as reinforcements to bolster Syrian government forces.

Another key supporter is Russia. Having maintained military bases in Syria before the conflict, Russia dispatched mercenaries and exported weapons shortly after it began, and in 2015 it formally announced its intervention. While Russia entered under the banner of “fighting terrorism” represented by IS, it also coordinated with Syrian government forces to attack moderate opposition groups. It has repeatedly carried out airstrikes targeting extremist groups including IS, with reports that many civilians have been killed in these strikes. Furthermore, in 2017, Russia negotiated with several opposition groups previously backed by Western countries and succeeded in securing a halt to military activities. With Russia’s support, Syrian government forces recaptured territory held by the opposition one after another.

On the other side, the opposition has been supported by the United States, Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other Western and Gulf countries.

The United States deployed ground troops in Syria and initially stated it would support groups it deemed moderate. In practice, however, it ran a covert program called “Timber Sycamore” through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that militarily supported opposition forces, including extremist groups, and trained fighters. Conducted jointly with Saudi Arabia and others, the program provided weapons and funding via Saudi Arabia while the CIA provided military training. In addition to this program, the U.S. has also supplied weapons to al-Qaeda-linked extremist groups to overthrow the Syrian government. As noted, the U.S. initially considered IS useful, and later airstrikes to defeat IS reportedly caused many civilian casualties. In 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump announced a U.S. withdrawal from Syria, but quickly reversed himself, and U.S. forces continue to be stationed in Syria without the government’s permission. As of 2022, some about 900 U.S. troops remain in northeastern Syria, the autonomous area controlled by the U.S.-backed SDF, carrying out airstrikes and other military operations.

Turkey is a principal supporter of the opposition, but its objective has been identified as using opposition forces to suppress Kurdish groups inside Syria. The Turkish government clashes with the Kurdish PKK domestically and designates it a terrorist organization. Turkey thus views Syrian Kurdish forces as a threat and has vowed to absolutely prevent the emergence of a Kurdish state in Syria. Since 2016, Turkey has launched multiple incursions into Kurdish-controlled areas and occupies territory about 30 kilometers deep from the Turkey–Syria border. Beyond occupation, Turkey has mobilized the opposition forces it backs to carry out massacres of Kurds in northeastern Syria. Turkey has also reportedly conducted drone and air strikes on SDF positions as documented.

Israel, which is hostile to Iran, has also provided military support to anti-government forces. It has carried out airstrikes on positions recaptured by Syrian government forces from the opposition. Actions targeting infrastructure have also been reported, such as missile strikes on Damascus airport and Latakia port.

An expanding humanitarian crisis

As noted above, parts of Syria, including areas near the Turkish border, remain in a state of conflict. A major problem is that the reconstruction of cities and facilities destroyed by the war has made little progress, resulting in a severe humanitarian crisis.

According to the United Nations, 90% of Syrians live below the poverty line, and 70% face severe food insecurity right now. It was projected that in 2023 the number of people in need inside Syria would reach 15.3 million. Note that this estimate preceded the February 2023 earthquake; the number of people needing assistance is now thought to far exceed 15.3 million.

Humanitarian crises often persist long after active hostilities end. In Syria, however, several other factors are believed to be driving the crisis’s rapid worsening.

One is the stringent sanctions imposed on the B. Assad government by the United States and European countries since 2011. UN Special Rapporteur Alena Douhan has reported that these measures severely hinder the country’s recovery, arguing that reconstruction will continue to be obstructed unless sanctions are lifted. However, Western countries, led by the United States, have indicated a policy of maintaining sanctions until regime change occurs in Syria, with no sign of lifting them. Moreover, U.S. forces are currently stationed in areas with vast oil fields and are said to prioritize preventing the Syrian government from accessing these fields. This indicates an intent to block the Syrian government’s reconstruction and recovery efforts.

U.S. forces operating inside Syria (Photo: The National Guard / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Another factor is that aid from within and outside the country is not reaching all parts of Syria. The B. Assad regime has obstructed the flow of humanitarian assistance from NGOs and other groups linked to opposition-held areas, apparently to eliminate groups it sees as threats. It has also threatened and tortured Syrian humanitarian workers trying to deliver aid to opposition-held regions. Russia, which supports B. Assad, has also aided in blocking assistance to opposition areas by using its veto to shut down several UN cross-border aid routes that bypass the Syrian government. Currently, there is only one UN route through which aid can be delivered without interference from the Syrian government; if that route is closed, many more people are expected to fall into famine.

Turkey’s airstrikes, which have hit civilians and infrastructure, are also pushing Syrians into a dire situation. In particular, Turkish strikes targeting Kurdish-administered areas have destroyed medical facilities, schools, and energy infrastructure, severely worsening living conditions in northeastern Syria.

Other factors include the record cold wave that hit Syria from 2021 to 2022. Internally displaced people living in temporary shelters lack adequate clothing and heating equipment to cope, making their lives even more difficult. In 2022, a cholera outbreak occurred in Syria, with more than 20,000 cases. The outbreak stems from the collapse of medical infrastructure and contamination of water systems, requiring urgent action.

Finally, the major earthquake in February 2023 has further exacerbated the existing humanitarian crisis. In Idlib Governorate, which is held by the opposition, the necessary aid is not reaching people.

Toward resolving the humanitarian crisis

We have reviewed the course of the Syrian conflict and the problems it has created. Why, then, has such a severe humanitarian crisis not moved toward resolution?

One issue is how the actors involved engage with the conflict. As seen above, many countries have intervened in the Syrian war. Whether backing or seeking to topple the Syrian government, these countries have focused on military support and sanctions while often giving insufficient consideration to the harm inflicted on Syrian civilians. The legitimacy of actions—sanctions, airstrikes, destruction of infrastructure—that cause massive civilian suffering is questionable.

A street scene in Syria in 2022 (Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Another problem is declining attention. While the Syrian conflict drew global media attention when the conflict began and during the advance of IS, interest waned once those headlines faded. In 2022, Syria experienced its worst-ever humanitarian crisis, yet attention was lower than at the outbreak of the conflict or during the IS advance. Attention can, depending on its direction, risk fueling new, destructive interventions. But it can also function as a deterrent against actions that exacerbate crises. Low attention also means less humanitarian and reconstruction support.

The Turkey–Syria earthquake has again focused attention on Syria’s humanitarian crisis. To prevent further loss of life, we hope for longer-term attention and support for the Syrian conflict.

Note 1: People living across the region known as “Kurdistan” (land of the Kurds), spanning southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, and northwestern Iran. They are sometimes called “the largest stateless people.”

Note 2: An ideological movement in the Middle East aiming for transnational solidarity among Arab peoples; also called Arab nationalism.

Note 3: In Turkey, the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) was formed in 1978 and has sought independence or autonomy for Kurdish-governed areas. In Iraq, the KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) was founded in 1946, pursuing a legally recognized Kurdish autonomous republic within Iraq through negotiations and armed conflict with the Iraqi government.

Note 4: A Sunni extremist organization active mainly in North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. It primarily targets Western countries and Israel.

Note 5: A Lebanese organization with influence rivaling that of a state in parts of the Middle East. It now wields significant political and military power in parts of Lebanon and, in support of fellow Shi’a communities, has intervened in the conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen through military support and direct participation.

Writer: Seiya Iwata

Graphics: Takumi K

0 Comments