[This article contains content related to induced abortion and sexual violence.]

In recent years, across Latin America, a series of legal reforms guaranteeing abortion rights have followed large-scale, cross-border social movements. The most noteworthy developments include the legalization of abortion in Argentina in December 2020, Mexico in September 2021, and Colombia in February 2022. Meanwhile, in the United States, where abortion rights had long been protected, the Supreme Court overturned the precedent recognizing abortion rights in June 2022, and abortion ceased to be guaranteed as a constitutional right.

Though each of these is relatively major news around abortion rights, a significant regional disparity in the volume of coverage in Japanese media has become apparent. This article first explains the legal regulations and social movements surrounding abortion rights in Latin American countries. It then analyzes how much these were covered by Japanese media, in comparison with coverage of abortion rights in the United States.

A woman calling for legal and free abortion (Photo: ProtoplasmaKid / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

目次

Countries moving toward legalization of abortion

Behind the bans or strict regulations on abortion in Latin America lie religious beliefs. A large share of the population in Latin America is Roman Catholic, and in Catholic teaching, life is sacred regardless of whether it has been born; it is considered morally wrong to take the life of an innocent person, including a fetus (view). From this perspective, many countries strongly condemn abortion and strictly limit it by law. On the other hand, there are growing calls for abortion based on women’s right to choose for themselves, the need for safe abortion environments, and the protection of women who have suffered sexual violence.

The legalization of abortion in Latin America began with Cuba in 1965, followed by Guyana in 1995. These countries allow abortion up to the 12th and 8th weeks of pregnancy, respectively (Note 1). Subsequently, from the 2010s through 2023, five countries have shown movement toward legalization. Each is discussed below.

The first is Uruguay. Abortion was completely prohibited in Uruguay since 1938. From 1985 onward, bills to legalize abortion were proposed in parliament about 4 times, but none were approved. In 2008, a bill to legalize abortion was finally passed by parliament, but then-President Tabaré Vázquez exercised his veto, and legalization did not materialize. However, after the administration changed to President José Mujica, in October 2012, a vote in the Senate fully legalized abortion up to the 12th week of pregnancy.

The second is Argentina. Since 1921, abortion in Argentina had been legal only under specific conditions such as when the pregnant person’s life was at risk. In the 2010s, movements sought to legalize abortion regardless of risk to the mother, but even in 2018 the Senate rejected a bill to fully legalize abortion up to the 14th week of pregnancy, leaving the legal regime unchanged. In 2020, however, the situation shifted, and in December of that year abortion was fully legalized up to the 14th week. In addition, the law guaranteed that everyone could receive abortion care free of charge.

The Pope conducting Mass at a Catholic church in Mexico (Photo: Aleteia Image Department / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

The third is Mexico. Since 1931, abortion had been prohibited except in cases of pregnancy resulting from rape. However, after abortion was partially allowed in Mexico City in 2007, the state of Oaxaca followed in 2019, and the states of Hidalgo and Veracruz fully legalized abortion in 2021. Then, in September 2021, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling that criminal prohibitions on abortion are unconstitutional. Following that ruling, in 2021 the states of Coahuila, Colima, and Baja California, and in 2022 the states of Guerrero, Sinaloa, and Baja California Sur recognized abortion, bringing the total number of states that legalized it to 10 out of 32. While many states still have not legalized abortion, given the variation by state, de facto abortion became a right recognized by the constitution.

The fourth is Colombia. Abortion had been completely prohibited in Colombia since 1936. The change came 80 years later, in 2016, when the Constitutional Court ruled that a total ban on abortion violated women’s rights. With that ruling, abortion was legalized only in three cases: when the pregnant person’s life was at risk, when the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, or when the fetus had anomalies. Abortion in other cases was a crime, punishable by up to 54 months’ imprisonment for patients and doctors. The law changed further in February 2022, when the Constitutional Court fully legalized abortion up to the 24th week of pregnancy.

The fifth is Chile. Abortion had been completely prohibited in Chile since 1989. However, in August 2017, the Chilean parliament passed a law permitting abortion only when the pregnant person’s life is at risk, when the pregnancy is the result of rape, or when the fetus has anomalies. In 2022, a new constitution that included abortion rights was drafted. Had the referendum held in September of the same year approved it, Chile would have become the first country in the world to explicitly enshrine abortion rights in its constitution. However, the draft constitution was rejected, and the path to full legalization remains ongoing.

The Supreme Court of Mexico (Photo: ProtoplasmaKid / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

The grassroots power that moves the law

As seen above, legal frameworks guaranteeing abortion rights are steadily advancing across Latin America. Why, then, have similar moves toward legalization arisen in multiple countries at roughly the same time? One factor in the background is a movement known as the “Green Wave.”

Going back to 2003, efforts to legalize abortion were placed on the agenda of the National Women’s Meeting (ENM) in Argentina. This meeting brings together women from every region of Argentina to discuss how to achieve gender equality, and this development became a turning point that gradually set society in motion toward legalization.

By 2005, a civic group was formed in Argentina to support reform of abortion laws: the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion. Its symbol became the green bandana. The color green was chosen to represent vitality and health, and participants showed solidarity by wearing green bandanas. At the same time, the campaign carried the message that “abortion is healthcare and a lifeline for many women,” challenging Argentina’s limited access to abortion.

The campaign gained momentum with the feminist movement Ni Una Menos (“Not one woman less”) in 2015. Under the slogan that not one woman should be lost, demonstrations were held, and activists pressed lawmakers to enact policies protecting women from violence and femicide. Although the initial focus was on violence and murder against women, attention broadened to gender discrimination as a whole, and the importance of abortion rights began to be discussed as one way to protect survivors of sexual violence.

The movement spread rapidly on social media, drawing in many individuals and civic groups, especially among younger generations, and grew year by year. In 2018, hundreds of thousands marched through Argentine cities wearing green bandanas and clothing in support of legalization parades. From these scenes, the movement for abortion legalization came to be called the “Green Wave.” The power of individuals uniting at the grassroots level developed into a major movement that continued to press the government—ultimately contributing to legalization in 2020.

Women participating in the Green Wave movement in Argentina (Photo: María Belén Altamirano / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Argentina’s legalization helped spark Green Waves elsewhere. Across Latin America, many countries saw Green Wave actions that challenged closed or restricted access to abortion. As a result, Ecuador legalized abortion in cases of pregnancy resulting from rape, and Chile moved to guarantee abortion rights through a new constitution. Mexico and Colombia went on to legalize abortion. The Green Wave spread beyond Latin America to the United States as well. In May 2022, after a draft decision leaked from the Supreme Court indicating that the precedent upholding abortion rights was likely to be overturned, demonstrations with green bandanas and messages were held in multiple U.S. states (protests).

Countries that strictly restrict abortion

While the Green Wave has advanced legal reforms toward legalization in several Latin American countries, others have strictly tightened abortion regulations in recent years. A few of these are highlighted below.

First, Nicaragua. In November 2006, a law completely banning abortion was approved. For the prior 130 years, abortion had been allowed under special circumstances, but the Catholic Church in Nicaragua lobbied the parliament to pass a bill banning abortion. The bill was passed, and the law was amended accordingly. As a result, abortion became a crime under any circumstances, punishable by 6 to 30 years in prison.

Next, Honduras. In January 2021, a constitutional amendment explicitly banning abortion was approved by parliament, and the vote threshold to amend abortion-related laws was raised from two-thirds to three-quarters. Abortion had already been completely banned, and the use and sale of emergency contraception was also illegal and strictly controlled. By hardening the law and making it more difficult to overturn, legal restrictions were further tightened.

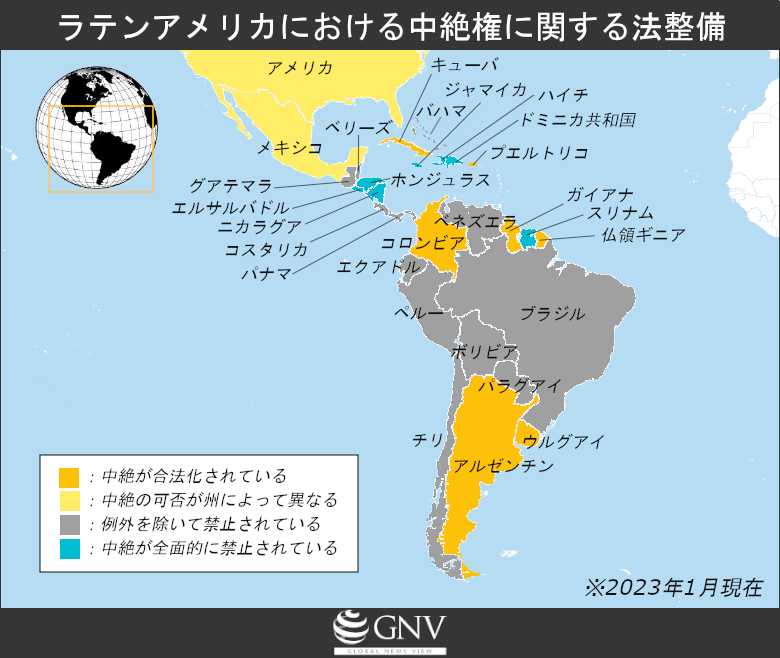

Created based on CENTER for REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS

The United States has also become one of the countries strictly regulating abortion rights. In June 2022, the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision (Note 2) was overturned. Roe v. Wade held that abortion fell under the constitutional right to privacy and thus recognized abortion rights. Based on this decision, abortion rights had been protected in the U.S., but with the Supreme Court’s reversal, abortion ceased to be guaranteed as a constitutional right. At the same time, authority was granted to each state to freely enact abortion laws. As a result, as of January 2023, 13 states banned abortion except in cases such as rape or incest; ultimately, it is predicted that about half of the states may impose total or partial restrictions.

Volume and content of coverage in Latin America

Thus far, we have outlined recent fluctuations in abortion rights in Latin America and the United States, the related social movements, and the legal regimes. In Japan, abortion up to the 22nd week is permitted under certain conditions by Article 14 of the Maternal Health Act. However, the necessity of spousal consent has stirred controversy, and Japan is not isolated from abortion issues. So how much were the developments in Latin America reported in Japan? For this analysis, we examined the volume of reporting over the four years from 2019 to 2022, a period of major social and legal changes around abortion rights. Using “abortion” as the keyword, we searched the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun, extracting only international reports whose main subject was abortion (Note 3).

Counting the relevant articles on Latin America, Asahi Shimbun ran 5 articles, Yomiuri Shimbun ran 3, and Mainichi Shimbun ran 0, for just 8 articles in total over four years (Note 4). Of these 8 articles, 3 concerned Argentina’s legalization in 2020 (two in Asahi, one in Yomiuri), and one (Yomiuri) concerned the 2021 Supreme Court decision in Mexico declaring penal state laws unconstitutional. In 2022, Asahi published 2 articles on the criminalization of stillbirths and miscarriages in El Salvador, one article on Brazil’s conservative values opposing abortion (Asahi), and one article on the Green Wave movement in Latin America (Yomiuri).

Argentina’s National Congress (Photo: GameOfLight / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

What, on the other hand, were not reported? First, the process of legalization in Argentina in 2020. As noted above, there were 3 articles on this topic. However, in Yomiuri’s sole article on Argentina, the content only reported the fact that a bill decriminalizing abortion had passed. Little was said about the long, labor-intensive movement toward legalization. Asahi had one article on demonstrations by both pro- and anti-abortion-rights groups. It also described the dangers of clandestine abortions under legal bans. Yet the road to legalization itself was not conveyed. Without background, such coverage is unlikely to foster understanding among readers unfamiliar with the issue.

Next, the Green Wave. Yomiuri ran one article on this movement, focused mainly on Argentina since 2020, with mention that Mexico, Chile, and Colombia eased requirements and that El Salvador and Nicaragua tightened restrictions. But this approach gives little sense of the Green Wave before 2020. Moreover, it barely touched on Green Wave activism outside Argentina, compressing it into the single phrase “the Green Wave is spreading in Latin America.” Can that phrase alone communicate regional dynamics and the scale of demonstrations that have erupted across locales?

Then there is Colombia’s legalization. While Yomiuri briefly mentioned it within the Green Wave article above, there were no articles focusing solely on Colombia. Colombia’s legalization is said to have been influenced by Argentina and Mexico. It sent a comparatively significant shock not just within Colombian society but across other Latin American countries and could be expected to spur future legalization elsewhere. Even so, it was barely reported in Japan.

Colombia’s Constitutional Court (Photo: Torax / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Lastly, the movement toward legalization in Chile. As with Colombia, this was only briefly mentioned within Yomiuri’s Green Wave article. Although not counted in our tally, there were a few articles whose main subject was the constitutional draft and referendum that listed abortion rights as one of the changes to be included in the new constitution. However, there was no reporting that treated the legalization of abortion in Chile as the main topic.

Volume and content of coverage in the United States

How much coverage did developments around abortion rights in the United States receive in Japan? Using the same method as for Latin America, we found that Asahi ran 30 articles, Mainichi ran 40, and Yomiuri ran 40, for a total of 110—about 14 times the coverage of major developments across several Latin American countries. By year, coverage concentrated in 2022, with 69 articles (Asahi 20, Mainichi 25, Yomiuri 24), the most of any year. In all three papers, each year from 2019 to 2021 had fewer than 10 articles (Note 5), with roughly 60% of the four-year coverage appearing in 2022.

The reason for the high volume in 2022 is, unsurprisingly, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, as our analysis shows. Of the 69 articles, 44 were about the ruling declaring the 1973 decision unconstitutional. Looking across the four years by topic, nothing matched this in volume. The second most-covered topic was the 2021 Texas law banning abortion after 6 weeks, with 18 articles, followed by 16 articles on the 2022 midterm elections in which abortion restrictions were a key issue. Coverage of the ruling overturning Roe included not only reports that the law had changed, as with Argentina’s legalization, but also extensive reporting on pre-decision developments, the legal content, and the political and social impacts after the change. This underscores how intensively that ruling was covered.

Other 2022 coverage included articles on tightened regulations in multiple states, reports on demonstrations against abortion restrictions, and reporting on the midterm elections where abortion was a central issue (Note 6).

Protest in front of the U.S. Supreme Court against the decision on abortion rights (Photo: Ted Eytan / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.0])

What does the difference in coverage mean?

Our analysis shows that while there were only 8 articles over four years covering all of Latin America’s abortion issues, there were 110 articles on the United States in the same period—a stark contrast. It was also notable that Mainichi did not once make any Latin American abortion development the subject of an article. As discussed, several countries in Latin America experienced major developments around abortion rights, and there were large-scale, cross-border citizen movements pushing for legalization. Nevertheless, coverage of Latin America was less than one-tenth that of the U.S. On the same issue—women’s bodies and abortion—events in the United States drew great attention, while interest in Latin America was extremely thin.

Why such a gap? There are many reasons coverage varies, but the chronic scarcity of reporting on Latin America likely plays a major role. Indeed, it’s telling that major Japanese newspapers maintain bureaus only in Brazil and Cuba in the region, suggesting it is not treated as a priority. As GNV has covered in a past article, coverage of Latin America accounts for only about 2% of international reporting.

Does that mean developments around abortion in Latin America have low news value? Quite the opposite. Beyond the Green Wave, feminist movements in Latin America are occurring across borders at regional and even continental scales, and their magnitude deserves attention. The movement is also said to offer lessons for the United States today, including strong activist solidarity and backing from large human rights organizations. Above all, abortion rights—included in human rights—are universal and should not vary by country or region. Just as abortion in the United States is covered in Japan, there is great value in reporting Latin America’s developments to foster understanding as part of human rights and feminism.

The green bandana, a symbol of the abortion rights movement (Photo: Fotomovimiento / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

This article focused on abortion rights to compare how Latin American countries and the United States are treated in the news. Such biases in coverage are by no means limited to abortion. Around the world, events continue to occur that go unreported and thus unknown in Japan. Of course, it is impossible to report everything, but news organizations are the primary information source for readers to learn about the world. Precisely for that reason, they should help readers grasp global issues. To do so, it is important not to focus primarily on particular countries or regions, or on a single point within long-standing issues, but to report in a balanced and panoramic way.

※1 Generally, the first day of the last menstrual period is counted as 0 weeks and 0 days, and birth occurs in the full-term period from 37 weeks 0 days to 41 weeks 6 days. Signs of pregnancy typically appear around weeks 5–6, and ultrasound can detect a fetus of about 1 cm and a fetal heartbeat. Morning sickness commonly begins around week 8, and pregnancy enters a more stable phase through week 13. Around that time, the fetus grows to about 10 cm and about 30 g, and the face and body become visible. Around weeks 18–20, fetal movement can be felt and sex can be identified. Around week 30, the fetus is about 30 cm and about 1 kg, and by birth about 50 cm and about 3 kg. The number of weeks to birth, circumstances, and fetal growth vary by individual.

※2 The case began when “Roe” (a pseudonym), a pregnant woman living in Texas, sought an abortion and learned that, under Texas law, abortion was not permitted unless the pregnant person’s life was in danger. She objected and filed suit. Combined with the name of the Texas district attorney who was the defendant, Wade, the case came to be known as Roe v. Wade.

※3 To examine coverage volume, we used Asahi Shimbun’s online database “Asahi Shimbun Cross Search,” Mainichi Shimbun’s online database “Maisaku,” and Yomiuri Shimbun’s online database “Yomidas Rekishikan.” From January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2022, we searched the keyword “abortion” and extracted only the relevant articles from international reporting, regardless of morning or evening editions. Here, “international reporting” includes not only articles categorized on the international page of each paper, but also other sections covering events that occurred outside Japan.

※4 The details of the 8 articles are as follows.

Asahi Shimbun:

2020年 12月25日 “Abortion bill divides Argentina: Legalization debate enters final stage; protests by both supporters and opponents”

2020年12月31日 “Argentina passes bill legalizing abortion”

2022年 7月6日 “Woman with stillbirth sentenced to 50 years in prison: El Salvador, convicted of aggravated homicide”

2022年9月14日 “11-year-old becomes pregnant; mother refuses abortion: Conservative values in Brazil cause shock; assaulted by relative, had already given birth to a boy a year and a half earlier”

2022年12月13日 “(From the world 2022) Countries where stillbirths and miscarriages become murder: El Salvador, where most people are Catholic”

Yomiuri Shimbun:

2020年 12月31日 “Bill legalizing abortion passed”

2021年 9月9日 “Mexico paves way to legalization of abortion: Supreme Court rules state law with penalties ‘unconstitutional’”

2022年 8月22日 “Latin America moves to legalize abortion: Support grows for ‘Green Wave’ movement”

※5 Coverage volume for 2019–2021 was as follows.

2019: Asahi 1, Mainichi 3, Yomiuri 3, total 7

2020: Asahi 3, Mainichi 3, Yomiuri 3, total 9

2021: Asahi 6, Mainichi 9, Yomiuri 10, total 25

※6 In 2019, there were 7 articles in total: 4 on debates and demonstrations over legal restrictions on abortion (two each in Mainichi and Yomiuri), 2 on Alabama’s law banning abortion with limited exceptions (one each in Asahi and Yomiuri), and 1 on Georgia’s law banning abortion after 6 weeks (Mainichi).

In 2020, there were 9 articles: 5 on Louisiana’s law banning abortion after the 15th week (Asahi 1, Mainichi and Yomiuri 2 each), 3 on anti-restriction demonstrations (one in each of the three papers), and 1 on the Supreme Court’s conservative shift (Asahi). Note that the anti-restriction demonstrations featured a speech by former President Donald Trump, and all relevant headlines mentioned him, giving the impression that the focus was more on his stance and actions than on the demonstrations themselves.

In 2021, there were 25 articles: 18 on the Texas law (Asahi 4, Mainichi and Yomiuri 7 each), 3 on Mississippi’s law banning abortion after the 15th week (one in each paper), plus one on President Joe Biden’s stance toward abortion restrictions (Mainichi), and one each on demonstrations over abortion rights and on a rising political faction (both Yomiuri).

In 2022, there were 69 articles: 44 on the ruling declaring the 1973 decision unconstitutional (Asahi 13, Mainichi 17, Yomiuri 15), 16 on the midterm elections in which abortion restrictions were a key issue (Asahi 4, Mainichi 5, Yomiuri 7) (Note 7), 3 on Oklahoma’s law banning abortion with limited exceptions (Asahi 2, Mainichi 1), 3 on Kansas’s law legalizing abortion up to the 22nd week (one in each paper), and one each on President Biden’s views on abortion restrictions (Mainichi) and Idaho’s law banning abortion after 6 weeks (Yomiuri).

※7 Among the midterm election articles, we counted those that addressed abortion restrictions. The criteria were: the article included an explanation of abortion restrictions and/or the word “abortion” appeared in the headline. Articles that mentioned “abortion” in passing only as one of several issues, without explanation, were not counted.

Writer: Mayuko Hanafusa

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

0 Comments