The Mekong River is the source of life on the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia. People have eaten fish caught in the river, built houses with sand collected from it, and grown crops with its water. For a long time, it has supported the lives of millions living along its banks. However, in late 2019 in May, unlike in typical years, the monsoon rains failed to arrive, and the environment began to change. A drought set in, and water levels fell to their lowest in the past 100 years. Since then, the rains have been scant, and the drought has persisted to this day. In fact, Cambodia, one of the countries that relies on the Mekong, has warned its citizens that with the precipitation expected in 2022, the rainy season may not come. Without a rainy season, only about 20% of the water needed to operate essential agricultural irrigation systems would be available, and immediate public needs could not be met.

In tributaries of the Mekong flowing through Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos, the river’s current is reportedly almost at a standstill. Downstream on those tributaries, changes beyond lower water levels have appeared: the water has shifted from brown to clear. Clear water contains little sediment and is nutrient-poor. As a result, inland fish catches in the region—once the world’s largest—have plummeted and now barely suffice to feed farmed fish. The Mekong River has undoubtedly reached its limits.

A Cambodian floating house standing on parched ground (Photo: Simon_Goede [Pixabay License])

目次

The Mekong River

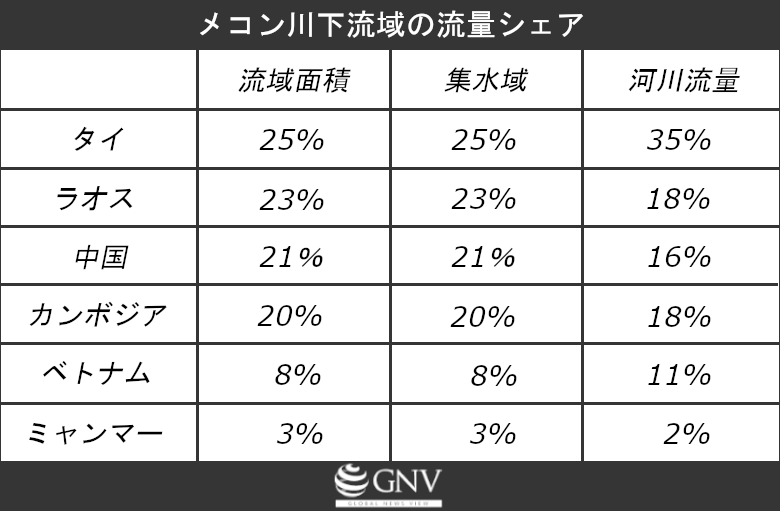

The Mekong is the 12th-longest river in the world and the 3rd-longest in Asia, stretching about 4,909 km. Rising on the Tibetan Plateau, it runs through six Asian countries—China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam—and about 65 million people depend on it for their livelihoods. Geographically, the river is split into two parts: the upper reaches, mainly in Tibet, and the lower reaches from China to the South China Sea. The upper basin accounts for about 24% of the total area and flow. The flow share in the lower basin is as shown in the table below.

Biodiversity in the Mekong basin is said to be second only to the Amazon globally, and the highest in the world per hectare. As a result, the Mekong is one of the world’s richest inland fisheries. It yields 2 million tons of fish for food each year, plus nearly 500,000 tons of other aquatic life (freshwater crabs, shrimp, snakes, turtles, frogs, etc.). For example, in Cambodia about 80% of annual protein intake comes from fish caught in this river, and at present there is no substitute food source.

In 1995, the governments of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam in the lower Mekong established the Mekong River Commission (MRC) to manage and use the Mekong’s water and other resources sustainably. The commission’s main roles are to monitor the basin, collect and analyze data, and coordinate planning and dialogue. China and Myanmar, also riparian countries, are not directly involved in the commission, but both are MRC dialogue partners and cooperate on joint studies and technical exchanges.

Created based on MRC data.

A river in decline

Climate change is affecting many parts of the planet, and as noted above, the Mekong is no exception. The prolonged drought in the region since 2019 has been driven in part by El Niño. The El Niño phenomenon is a periodic warming of sea-surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific. It alters weather cycles and reduces rainfall. Its impacts reach not only the Mekong basin but also many equatorial nations.

The Mekong supports robust inland fisheries. One of their hubs is Cambodia’s Tonle Sap, Southeast Asia’s largest lake and the “heart of the Mekong.” In normal rainy seasons, the lake’s area expands by about 40%, creating crucial habitat for fish. The lake yields 500,000 tons of fish annually—more than North America’s catches. But during the 2019 drought, rainfall was insufficient and inflow from the Mekong was low, so instead of expanding the lake’s level dropped. This hindered fish reproduction and left communities short of water for daily use. In one floating village that normally rises with the wet season, water that never dries up even in the dry season ran dry.

Under these conditions, fish catches in Tonle Sap have fallen by as much as 90%, and many fishers reportedly have had to give up. In fact, of the 60 “dai” (Cambodia’s traditional trawl nets) fishers who set fixed nets in the lake, more than one-third could not even start their season in 2019. Even if they did fish, the catch would not meet people’s needs and would be used only as feed for fish farms. As fish are the main source of protein for Cambodians, the country faces the risk of large-scale food insecurity.

Large-scale dam projects

As of 2020. Based on Stimson data.

Laos also plans to build hundreds more hydropower plants and become the “battery” of Southeast Asia. It already operates 78 dams with a generation capacity of 45,480 megawatts. Cambodia likewise announced plans to build two dams on the river. However, citing environmental concerns, those plans were scrapped in 2020, and no dams will be built until 2030.

Currently, however, it is not only Southeast Asian countries that operate dams. In China, the first country the river traverses, 11 giant dams have been built. When China first began building dams in the 1990s, concerns grew that it would be able to control the flow at will. Indeed, during the major drought in 2019, Chinese dams are believed to have impounded more than 12 trillion gallons of water—about half the Mekong’s flow. Because snowmelt and precipitation on the Chinese side were normal, water levels downstream would likely have been close to normal had the water not been held back. These dams are severely disrupting flows downstream.

Dams store and release vast amounts of water, greatly altering river flow and harming natural processes such as fish migration and riverine biodiversity. Without migration, fish cannot spawn and reproduce, leading to shortages. Sudden rises in water level can sweep away crops and livestock, often disrupting local economies. Conversely, when water is held back, insufficient volumes reach downstream areas for agriculture.

It is believed that fish can tolerate a certain degree of natural variability, but not when the changes are artificial. Existing dams in fact impede the migrations of about 160 species across the Mekong basin, many now at risk of extinction. For example, by 2010 the population of the Mekong giant catfish had fallen by 90% compared to a decade earlier. The MRC reports that of the 692 freshwater fish species in the lower Mekong, 68 are endangered and 22 are threatened.

China’s Xiaowan Dam (Photo: Water Alternatives Photos / [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In some places, especially at the river’s end, water shortages have triggered saltwater intrusion, as in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Normally, even if seawater enters a river, freshwater flowing downstream flushes it out quickly. But with reduced volumes in the Mekong, the intruding seawater is no longer pushed back and penetrates deep into the delta, lingering with high salinity. Agriculture around the delta has been hit hard. In Ben Tre―, Vietnam, for example, rising salinity caused entire fields to wither. Traditionally, saltwater intrusion was rare in this region. Under current conditions, fruit such as durian and rambutan—long cultivated here—can no longer grow, and people have to buy water in addition to what they draw from the river. Irrigation requires 5,000 liters of water per day 5,000 liters daily, and some households have gone bankrupt because they could not secure it.

Dams also block not only water but sediment. Soon after Laos’s Xayaburi Dam began operating, river water that is normally chocolate-brown turned a clear blue in the south, indicating the loss of the river’s usual rich nutrients. Similar conditions have been observed in Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia, and are expected to spread. Such changes have also triggered a phenomenon known as “hungry water,” in which riverbanks are eroded. Water without sediment flows faster and is more erosive. These conditions have led to algal growth on sandy and rocky riverbeds. The presence of algae in freshwater can pose a threat to fish and other aquatic life.

Excessive sand extraction

When people think of mining, they often picture “valuable” materials like gold, diamonds, or coal. In reality, sand is extensively mined worldwide. Sand is indispensable for concrete and is said to be the world’s second most extracted resource after water.

River sand in particular is the most sought-after because of its durability. By contrast, marine sand contains salt and corrodes easily; its grains are round and bind poorly, so it is rarely used for construction. Such sand extraction is conducted on the Mekong, especially in the delta.

Sand mining on the Mekong River (Photo: Water Alternatives Photos / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

The Mekong Delta is a deltaic region of which Cambodia holds about 16,000 square kilometers and Vietnam about 39,000 square kilometers. In Vietnam in particular, the delta has been intensively developed for agriculture. At the same time, large-scale sand extraction is taking place, pushing the river to crisis.

In Vietnam, more than 80 companies are licensed to extract 28 million tons of sand annually. Because most extraction occurs underwater, however, it is extremely difficult to measure actual volumes. Authorities therefore rely on self-reporting, and illegal mining is believed to occur. In 2018, 20 million tons were said to have been extracted in the Mekong Delta, but satellite imagery and observations indicate that more than double that—43 million tons—was actually removed. In 2020, an estimated 47 million tons were extracted.

Large-scale sand mining in rivers clearly has severe environmental impacts. Sandy riverbeds are home to many plants and animals; removing sand destroys these habitats and damages ecosystems, reducing biodiversity. At the same time, extraction deepens the channel and lowers water levels. In the Mekong, the bed is reported to be deepening by 20–30 centimeters per year.

Another grave impact is bank erosion. According to Vietnam’s Water Resources Institute, erosion is occurring at more than 620 sites—roughly one site per kilometer of the delta. Because upstream dams trap not only water but sediment, sand mined downstream is not replenished, contributing to the “hungry water” phenomenon described above.

In and around the Mekong Delta, where about 20 million people live, 54% of Vietnam’s rice, 70% of its seafood, and 60% of its fruit are produced, accounting for more than 17% of national GDP. Likewise, Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh lies just north of the delta; if the delta’s environment is degraded, it will pose a major threat to many people’s economies and livelihoods.

Fishers on Tonle Sap (Photo: Water Alternatives Photos / [CC BY-NC 2.0])

So, what should be done?

The countries of the Mekong basin each face their own worries: severe water shortages in Thailand, severe food shortages in Cambodia, and erosion and saltwater intrusion in Vietnam’s delta. Despite their heavy dependence on the river, government responses have been deemed insufficient in terms of mitigating impacts and building resilience. Nor are the governments aligned. For example, despite opposition from Thailand, Laos plans to build 100 dams by 2030.

In this context, the MRC is expected to play a stronger role. In the past, the MRC consisted of Southeast Asian countries and was seen as politically weak because China was not a member. China, for its part, launched the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism. The two bodies signed a pledge to cooperate more closely. This is expected to shed some light on China’s activities in the Mekong basin. For example, when China conducted an experiment at the Jinfeng Dam, it notified downstream countries one week in advance that flows would decrease. This is a good example, but the sustainable management of this international river will require continued effort and proactive engagement by all parties.

Writer: Syafiq Syaikhul Akbar

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

Translation: Yosuke Asada

島国である日本は他の国と奪い合う必要がないため、これまで想像もしていなかったのですが、この記事では丁寧に取り上げられていて理解が進みました。ありがとうございました。

Twitterで「茶色の水が透明に」という文言に惹かれて拝読させていただきました。

水の色が透明になることの背景・弊害について、詳しくまとめられており、大変勉強になりました。