In Vietnam, the number of arrests for political offenses has increased in recent years. According to Amnesty International, as of 1/2021 at least 170 people were detained, the highest number since 1996. It has also increased by more than 2 times from the 84 people detained at the time of the 2016 Communist Party Congress. Those arrested include journalists and bloggers who discussed criticism of the government, social media users, as well as ethnic minorities and religious minorities living in Vietnam.

Vietnam’s population is composed of about 13% ethnic minorities spread across more than 90 groups. Among them, 53 minority groups are officially recognized by the government, while others are not. Each group has distinct languages and cultural backgrounds. Although Vietnam has experienced economic growth in recent years, compared with the majority population, many ethnic minority people remain in significant poverty and are often subject to political repression. This article explores the background to the social vulnerabilities faced by Vietnam’s ethnic minorities and the resulting poverty.

Hmong woman (Photo: Rod Waddington / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

目次

Minorities in Vietnam

Vietnam is located on the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula and stretches long from north to south. Its population is about 98 million, of which about 87% identify as Kinh (Kinh). They mainly live in the deltas and coastal plains where most major cities are located. Many Kinh report no religious affiliation, but it is estimated that 13.7% practice Mahayana Buddhism.

By contrast, ethnic minorities, who make up about 13% of Vietnam’s population, often live in the mountainous and hilly regions that account for three quarters of the country’s land area, far from urban centers. Minority groups also differ in language and religion. Looking at the population shares of minority groups, in descending size they include Tay (Tay (※1)) at 2.0% (1.96 million), Thai (Thai (※1)) at 1.9% (1.862 million), Muong at 1.5% (1.47 million), and Khmer Krom at 1.5% (1.47 million) (※2). Religions practiced by minorities include Theravada Buddhism, the Catholic Church, the indigenous Vietnamese Hoa Hao and Cao Dai, Protestantism, Hinduism, and Islam.

Cao Dai ceremony (Photo: Shawn Harquail / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

History of Vietnam

Vietnam encompasses diverse peoples but forms a single nation-state today. How did the country take its current shape? Let’s review the history of the region that is now Vietnam.

From the 2nd century BCE, Kinh people are thought to have lived from what is now northern Vietnam into southern China. In the 1st century BCE, the Qin (then rulers of China) established the kingdom of Nanyue across what is now southern China and northern Vietnam. Until the 10th century, Nanyue maintained a degree of autonomy while remaining under the sway of Chinese dynasties such as the Han, Sui, and Tang. Meanwhile, present-day central Vietnam was ruled by the Cham, the kingdom of Champa, and the south was controlled by the Khmer Empire, centered in what is now Cambodia.

In the early 11th century, the region gained independence from China and established Dai Viet in what is now northern Vietnam, which became a long-lasting dynasty. From the 11th to the 15th centuries, Dai Viet, the Champa kingdom, the Khmer Empire, and Ming China fought repeatedly over territories including what is now Vietnam. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Champa was attacked by the Khmer Empire and declined. The Khmer Empire also withdrew from Champa in 1220 and similarly waned. Dai Viet, for its part, was repeatedly subject to Chinese interference. In 1406, it came under Ming rule, but about 20 years later regained independence and entered into a tributary relationship (※3) with the Ming.

Sculpture said to have been made in the Champa kingdom (Photo: Daniel Mennerich / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In 1471, Dai Viet captured Vijaya, the long-contested capital of Champa. This strengthened Dai Viet’s control not only in the north but also in the southern regions that include present-day Ho Chi Minh City. Population movements followed: more Kinh migrated from the north to the south, and many Cham and Khmer living in the south were incorporated into Dai Viet’s territory and forced to assimilate to Kinh culture.

In the 16th century, royal authority in Dai Viet weakened and powerful warlords took control, splitting the realm again between north and south. At the end of the 18th century, Nguyen Phuc Anh in the south subdued the north in 1802, renamed the country Viet Nam, and unified what is now the whole of Vietnam. During this conflict, French missionaries active in Southeast Asia organized volunteer forces to aid the Nguyen. This is believed to have been because, amid European colonial expansion in Asia, France sought to expand into Viet Nam. Viet Nam responded by adopting isolationist policies and banning Christianity.

In the mid-19th century, citing the killing of French and Spanish missionaries in Viet Nam as a pretext, Napoleon III of France invaded Viet Nam. Viet Nam’s forces resisted, but after landings at Da Nang and the occupation of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), France took about 2 years to subdue the southern region including Saigon (Cochinchina).

France then expanded its control over Indochina, invading Cambodia and northern Viet Nam and making them protectorates. It also defeated the Qing, Viet Nam’s putative suzerain, compelling international recognition of Viet Nam’s incorporation into the French empire. France later made Laos a protectorate as well, and by the end of the 19th century had consolidated the region as the French Indochinese Union.

Under French rule, Indochina saw the introduction of Western education in sciences and geography, as well as Roman Catholicism. France also pushed development of the highlands to establish plantation agriculture. Meanwhile, after the Russian Revolution in 1917 established the Soviet Union, the Comintern supported colonial liberation movements, and under French rule in Indochina, communist parties, communist ideas, and calls for independence emerged. France, however, sought to suppress these movements.

The Second World War began in 1939 and France declared war on Germany, but in 1940 Germany occupied Paris and France surrendered. With France weakened, Japan occupied Vietnam from 1940 to 1945.

When Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945, the Viet Minh, a national united front organized chiefly by the Indochinese Communist Party, launched a general uprising against the stationed Japanese forces and established a provisional government, declaring independence as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. France, seeking to reimpose colonial rule in Indochina, began war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with support from Britain and the United States. The conflict dragged on until 1954, when the Democratic Republic of Vietnam prevailed and concluded a ceasefire agreement with France. The agreement temporarily divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel and stipulated national elections for reunification in 1956.

However, the United States and (South) Vietnam refused to hold those elections, and they were never conducted. The United States then established the Republic of Vietnam in the region south of the 17th parallel, dividing the country into the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and the Republic of Vietnam in the south. As the United States increased military support to the Republic of Vietnam, the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) emerged to oppose both, aiming for unification under the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and receiving support from it. Although the trigger is debated, after the United States began bombing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1965, the Second Indochina War (the Vietnam War) began. After a long and intense war, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north won in 1975, reunifying the country as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (hereafter, Vietnam).

Proclamation of the establishment of the Republic of Vietnam (Photo: manhhai / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

In 1978, citing Cambodian incursions across the border, Vietnam invaded Cambodia, and the following year seized Phnom Penh. China, which had friendly ties with Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime, invaded Vietnam, sparking the Sino-Vietnamese War, but China soon withdrew and Vietnam prevailed. However, decades of war since 1945 and rapid socialist transformation after reunification led to economic stagnation and prolonged hardship. In 1986, the Doi Moi policy introduced market-oriented reforms, easing strict socialism and promoting international economic cooperation. As part of this shift, Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia and concluded a peace agreement in 1991.

Thus, Vietnam’s borders expanded and contracted through conflicts with neighbors and periods of foreign occupation, often cutting across ethnic settlement patterns. Moreover, human movement is inherently fluid due to major political changes and wars that drive people to seek refuge in neighboring countries. As a result, the same ethnic groups may straddle borders, distinctions between groups may blur, and people may assimilate into the states to which they move. Such complex interweaving of identity occurs worldwide. Vietnam is one such case.

Educational issues and the cycle of poverty faced by minorities

After this history, today’s Vietnam is home to many groups, including numerous ethnic minorities. Among them, as minorities, people in a marginalized position face various problems. One of the most serious is poverty. Despite Vietnam’s recent economic growth, about 9 million people (※4) live in extreme poverty as defined by the World Bank (income of less than US$1.9 per day), and about 6.6 million, or roughly 73%, are ethnic minorities. In other words, compared with the majority Kinh, ethnic minorities are disproportionately likely to be living in poverty.

As factors driving poverty in Vietnam, World Bank staff point to five aspects: first, residence in remote highlands and mountains with poor market access; 2nd, social exclusion based on minority languages and cultures; 3rd, limited access to quality land for agriculture and forestry because most land is state-owned; 4th, low levels of migration for education and work; and 5th, low educational attainment. These factors do not act in isolation. Rather, one factor can trigger another, interacting to produce problems. Among these, we focus here on education, which is closely linked with many of the other drivers.

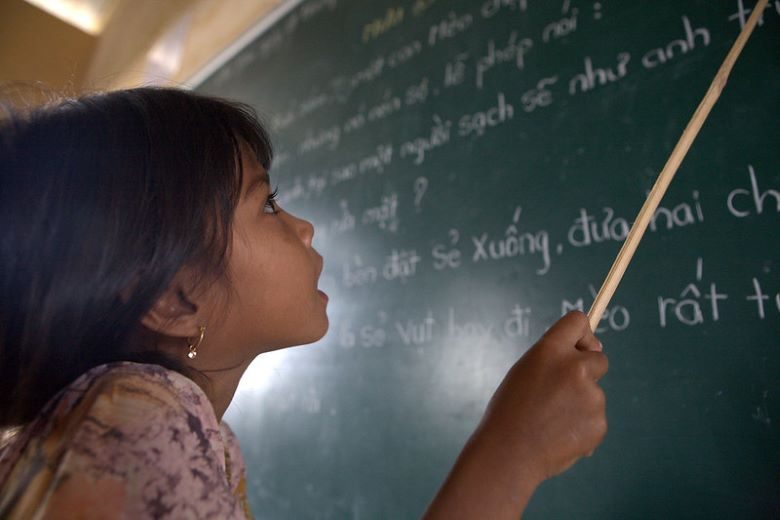

Khmer child learning Vietnamese (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

Regarding education levels, there is little difference in enrollment in primary and lower secondary education, but at the upper secondary level a large gap emerges between Kinh and minorities. While 74% of Kinh attend upper secondary school, many minority children do not advance, and only 44% attend upper secondary school. Minority children are also more likely than Kinh children to be behind grade level. Among minority children aged 15–17, the age range for upper secondary school, about 12% are still enrolled in lower secondary school, higher than the 7.5% of Kinh of the same age. There is also a large literacy gap. Among those aged 15 and over, the Kinh literacy rate is 95.5%, a high level. On the other hand, though based on different data and thus not directly comparable, the average literacy rate across all 53 recognized minority groups is 79.8%. Looking at individual groups, the Tho (Tho), Muong (Muong), and Tay (Tay) have literacy rates comparable to the Kinh at 95%. By contrast, the La Hu have the lowest literacy at 34.6%. There are also 23 minority groups with literacy rates in the 40–60% range, indicating substantial disparities among minorities themselves.

One cause of these disparities is the language of instruction. In Vietnam, schooling is conducted primarily in Vietnamese as the medium of instruction. For minority children whose mother tongue is not Vietnamese, this creates challenges in daily life and studies compared with Kinh children who are native Vietnamese speakers, increasing the risk of dropping out. While it varies by school, some schools teach eight minority languages as subjects. Even so, the primary language used to study in school remains Vietnamese.

There are also differences in distance from home to the nearest school, which also affects children’s educational opportunities. Many minority children must travel long distances to school; some live from 9 km to 70 km away from a secondary school, according to data. Comparing distances from home to school between minority children in mountainous areas and others shows gaps of about 1.3 km at the primary level, 1.7 km at lower secondary, and 7.6 km at upper secondary, showing that schools are farther from minority children’s homes. The higher the level of education, the larger the distance gap, indicating that institutions offering higher levels of education are less accessible near where many minority children live, and attending them requires long commutes. In addition, where minority communities lack adequate infrastructure such as roads and transport, commuting takes even longer. In response, in 2013 the Vietnamese government created a boarding school system with subsidies for meals and lodging. By 2019, compared with before the policy, the number of boarding schools had increased by 7 and student enrollment had risen by about 28,000.

People crossing a suspension bridge (Photo: Peyman Zehtab Fard / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has widened educational disparities. Nationally, Vietnam’s electricity access rate is high, but some mountainous rural areas lack electricity, disproportionately affecting minorities living in these regions. Early in the pandemic, nationwide school closures were imposed to prevent infection. Provincial education authorities and schools created online education platforms to keep all students learning, but this ended up exacerbating disparities. Combined with a lack of electricity, households without internet access or appropriate devices for learning could not participate. In one area of Lao Cai Province in northern Vietnam, only 15% of children had the communication devices needed for education. Minority children thus lost access to schooling due to insufficient connectivity. As a result, the wealthy could continue learning while the poor could not, further widening educational inequality.

Political issues faced by minorities

So far we have discussed social issues, but the challenges minorities face are not limited to society; they also extend to politics. Some arise from the overall political situation in Vietnam, while others are specific to minorities. First, let’s look at how Vietnam is governed.

Vietnam is a one-party state led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). Although elections are held to choose National Assembly members and, institutionally, non-CPV members can stand as candidates, allowing citizens to vote and run, in practice the reality is that candidates are thoroughly vetted by the CPV, and social activists or anti-communist figures are barred from running. This enables the CPV to avoid opposition and maintain strong influence. While elections exist, they are far from free and fair.

Moreover, freedom of expression regarding political views and criticism of the government is strictly limited. Vietnam consistently ranks low in the World Press Freedom Index, coming 175th out of 180 countries in 2021. Because criticism of the government is prohibited under the criminal code, media and academics who criticize authorities face arrest, violence, and other serious physical risks as a consequence. The government has also strengthened censorship and takedown requests for content on Facebook and Google under the Cybersecurity Law adopted in 2018. Under such conditions, it is difficult for Vietnamese citizens, including minorities, to raise political voices about social issues, and bottom-up solutions are hard to expect.

Flag of the Communist Party of Vietnam (Photo: Vuong Tri Binh / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

People’s religious practice is also placed under state oversight. The constitution recognizes equal freedom of religion. However, all religious organizations and clergy must participate in a state-managed supervisory body and obtain permits to conduct religious activities. Groups without such approval face daily harassment by authorities, including physical assault, arrest, surveillance, travel restrictions, and asset seizure or destruction. Reports of harassment are especially common in highland and mountainous areas where many minorities live. This control was further tightened by a 2016 law, which strengthened registration requirements, expanded the state’s ability to interfere in the internal affairs of religious organizations, and granted the government broad discretion to penalize unrecognized religious activities. As a result, engaging in religious practice not sanctioned by the state has become even more difficult.

Why does the state restrict people’s faith in this way? It is thought there are mainly three reasons. First, some religious affiliations are seen as potential threats to the government or the Communist Party. For example, during the Second Indochina War (Vietnam War), many Hmong who had become Catholic under French rule sided with the U.S. military. The distrust of minorities that this engendered within the Vietnamese government lingers to this day. The second reason is that, especially in rural areas, people may trust clergy more than government officials, creating the inconvenience that they heed clergy rather than officials. The third is a policy priority to maintain public order and morals over proselytizing and other religious activities.

Under these circumstances, ethnic minorities are forced to live with many constraints, both politically and in the practice of religion.

Toward improvement

We have examined the formation of ethnic minorities living in Vietnam and the problems they face. Through cycles of kingdoms rising and falling, territorial conflicts with neighbors, and other upheavals, Vietnam’s national territory took its present shape, producing a diversity of minority groups in the process. These communities still face numerous challenges and disadvantages. Given the restriction on political speech in Vietnam, it may be difficult to generate change from within by raising voices domestically. Recognizing the issues clearly outside Vietnam and calling for improvements may be one of the keys to a solution.

※1 The Tay and Thai referred to here are not related to the people living in today’s Kingdom of Thailand.

※2 Next in size are the Hmong (Hmong) at 1.3%, the Nung (Nung) at 1.2%, the Hoa (Hoa) at 1.0%, and the Dao (Dao) at 0.9%.

※3 The tributary system was a diplomatic order premised on the idea that China, the “Middle Kingdom” (Zhonghua) at the center of the world, bestowed benefits on surrounding “barbarians.” From the Ming onward, China regarded itself as the suzerain and other countries as vassals. Foreign rulers brought tribute to the Chinese emperor, who in turn granted gifts and invested them as kings, combining a diplomatic relationship with a trading system.

※4 GNV adopts an ethical poverty line of US$7.4 per day rather than the World Bank’s extreme poverty line of US$1.9 per day. For details, see the GNV article “How should we interpret global poverty?” However, due to insufficient data on the share of minorities within the number of people under the ethical poverty line, this article uses the World Bank’s extreme poverty line.

Writer: Yuna Takatsuki

Graphics: Mayuko Hanafusa

ベトナムで教育制度にこれほどの格差が生まれていることに驚いた。