Due to the spread of COVID-19, the number of people living below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line (less than $1.90 per day) is said to be increasing for the first time in 20 years. That number is expected to reach up to 150 million, accounting for 9.1~9.4% of the world’s population. In this situation, many countries are providing cash transfers as one countermeasure. Moreover, even after COVID-19 subsides, severe poverty is expected to persist. As an effective way to address poverty, there is a system that provides cash payments on an ongoing basis even in normal times. That is “Universal Basic Income.” This article introduces expectations and concerns about Universal Basic Income, as well as real-world implementation examples.

目次

What is Universal Basic Income?

Universal Basic Income is a scheme that guarantees citizens the minimum income needed to live, and is also referred to as “basic income” or “basic dividend.” “Universal” means it is for everyone, not targeted at specific groups. “Basic” indicates that the amount is sufficient for a minimum standard of living. And “income” means earnings. In other words, Universal Basic Income refers to “income provided to all people that is necessary to maintain a minimum standard of living.” Policies similar to Universal Basic Income have already been implemented in several countries in various forms. However, these have all been experimental or partial and do not necessarily satisfy the conditions of a true Universal Basic Income. According to the Stanford Basic Income Lab, UBI basically refers to something that satisfies the following 5 points: (1) it is paid to all people and does not target specific groups; (2) it is paid unconditionally; (3) it is paid to individuals rather than households; (4) it is paid regularly; and (5) it is paid in cash, with recipients free to use it as they wish. In practice, UBIs implemented or being implemented to date often take various forms, such as being based on means-testing, being conditional, or being introduced experimentally in limited regions.

It goes without saying that implementing UBI requires enormous funding, and the main sources are said to be three types: government debt, tax revenue, and funding from outside government. Funding from outside government refers, for example, to funds established from a portion of oil revenue. A related concept similar to UBI is the “negative income tax.” This idea is not new: around 1960, Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman supported a system in which cash is paid in proportion to income for those below a certain threshold. However, this presupposes that the recipient has some income, and thus differs from UBI, which is paid to everyone. As this shows, UBI and related concepts have been advocated for a considerable period. Still, UBI is controversial. Below we detail the expectations and concerns surrounding it.

Created based on data from the Stanford Basic Income Lab (as of 2021)

Expectations and concerns surrounding Universal Basic Income

First, consider arguments in support of UBI. To begin with, basic income is said to reduce poverty by ensuring people have a certain level of income. By guaranteeing a minimum income, it can also empower employees to leave poorly paid or exploitative jobs, preventing employers from continuing to hire under poor working conditions. As a result, there are views that poverty will decline through improvements in employment conditions.

Poverty reduction also has large spillover effects in other areas of society. With a steady income, people can pay consultation fees and visit hospitals in the early stages of illness, allowing treatment to begin before conditions worsen. Nutrition improves along with health status. Consequently, public health conditions are expected to improve. Regarding education, it can cover expenses like tuition, textbooks, and uniforms, and is expected to raise educational attainment. Moreover, as income stabilizes and financial pressure lessens, families become more stable, which is thought to reduce incidents of domestic violence and improve safety at home.

Beyond poverty reduction, UBI is believed to have positive effects across many aspects of life and society. By securing a minimum income, more people may start businesses without fearing risk, increasing the likelihood that new ventures beneficial to society and the economy will emerge. It is also expected to encourage adults to invest in their futures through education and vocational training. Since people have a certain income, they may devote more time than before to artistic and volunteer activities, making society richer.

Another expectation for UBI is that it can reduce costs and improve the efficiency of social security systems, according to some views. Existing programs are operated separately by purpose, resulting in many defects and overlaps; they are costly and may fail to efficiently reach those who need support. For example, among households with similar circumstances, some receive benefits from multiple programs while others fall through the cracks and receive none. Replacing these with a single, simple program in which individuals decide how to use the cash can make the social safety net more rational. Furthermore, existing systems determine eligibility, benefit amounts, and deductions based on means-testing and other surveys, which are costly to conduct and manage. Because basic income provides a uniform payment to everyone, those administrative and assessment costs are avoided. Thus, UBI is said to contribute to rationalization and cost reduction.

There is also research reporting that introducing UBI would increase consumption and stimulate the economy. According to the Roosevelt Institute, if every adult in the United States received $500 per month, consumption would rise and GDP would increase by up to 6.8% eight years after introduction. Lastly, there is an argument that UBI could compensate incomes for people whose jobs will be displaced by mechanization and AI. In the U.S., it is predicted that by 2032, one-third of workers will lose their jobs due to mechanization. With labor demand likely to shrink because of mechanization and AI, UBI is seen as a way to address decreased employment opportunities and incomes.

OECD Forum where basic income was discussed (Photo: OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development /Flickr)[CC BY-NC 2.0]

Next, consider criticisms of UBI. A frequent criticism is that UBI removes incentives to work and will make many people dependent on the government. In other words, if a certain income is guaranteed, people will feel less need to work and their willingness to work will decline. In fact, there are predictions that voluntary quit rates will accelerate as the benefit amount grows. If UBI is funded by tax revenue, people quitting would increase the tax burden on remaining workers, leading even more people to quit in a vicious cycle.

Contrary to the Roosevelt Institute’s findings, there are also projections that GDP would decline under UBI. According to Kent Smetters and colleagues at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, if every adult in the U.S. received $500 per month, within eight years government debt would rise by 63.5% and GDP would fall by 6.1%, they predict. By year 13, debt would be up 81.1% and GDP down 9.3%. In short, opinions are highly divided regarding UBI’s impact on GDP.

One background factor in projections of GDP decline is the cost required to implement UBI. It is frequently pointed out that UBI would be extraordinarily expensive. In a model from the University of Bath, even the lowest estimate suggests the UK would need about $190 billion annually. In low-income countries, while the guaranteed living income would be lower, fiscal resources are limited, so cost remains a high hurdle as in high-income countries. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, a living income sufficient for a decent life is estimated at $7,318 per year—far above the World Bank’s extreme poverty line ($1.90/day). High costs also mean that if funded by taxes, the burden on taxpayers—one of the funding sources—would rise. Therefore, it is pointed out that the tax burden on citizens could become heavy.

On the other hand, some supporters argue there are ways to ease UBI’s funding challenges. For example, by cracking down on companies and individuals that shift vast sums abroad through tax avoidance and evasion, governments could prevent revenue losses and secure tax income. Global tax losses due to corporate tax avoidance total $330 billion annually. This is enabled by mechanisms such as shifting profits from countries where real economic activity occurs to tax havens with little real activity, making it appear that profits were earned there and thereby escaping corporate taxes that should have been paid. Properly taxing corporations could recover substantial lost revenue and help fund UBI.

There are also proposals to address UBI’s cost by focusing on extreme global inequality, namely by further taxing the wealthy. According to Credit Suisse, the richest 10% of people own 85% of the world’s wealth. By strengthening taxation on the wealthy, who hold nearly 90% of global wealth, and using it as a funding source for UBI, the tax function of “redistribution of wealth” can be realized. Furthermore, to implement a basic income whose primary goal is poverty reduction, it is considered effective to stop government subsidies to companies engaged in unsustainable economic activities. For example, global fossil fuel subsidies amounted to $4.7 trillion in 2015. Since these hinder the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), some argue it would be more appropriate to stop such subsidies and allocate the funds to UBI.

In summary, we have outlined UBI and presented commonly cited arguments for and against it. Below, we detail, in chronological order, cases close to UBI that have actually been implemented.

Case study: Canada (Manitoba)

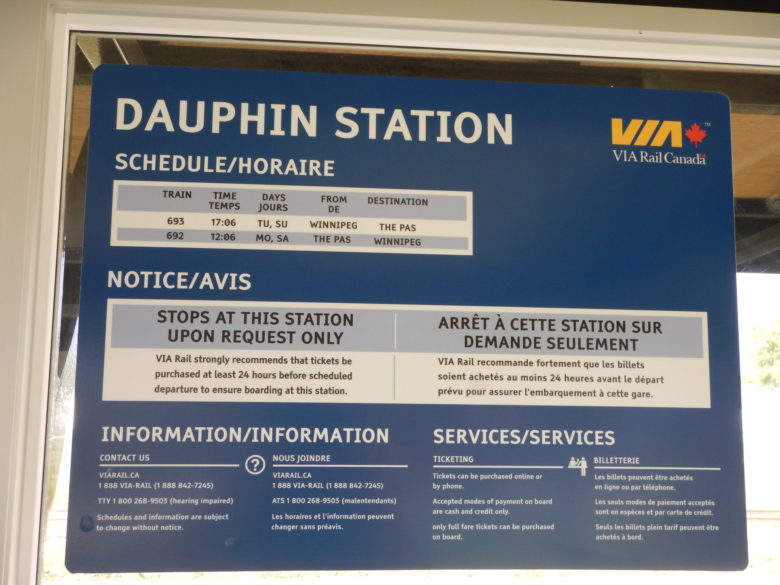

First, the “Mincome experiment” conducted from 1975 to 1978 in Dauphin and Winnipeg, Manitoba. Anyone in the lowest income bracket or their family was eligible to participate; about 1,500 households in Winnipeg and about 600 in Dauphin received benefits. The amount paid varied by family size, age, and income sources, but was about $250–$390 per month.

Dauphin (Photo: AI/ Flickr)[CC BY-NC 2.0]

This experiment revealed various results. To begin with, it showed that basic income improved people’s health. Compared with non-recipients, recipients’ hospitalization rates fell by 8.5%, and doctor visits also declined. High school completion rates rose as well. For example, before the experiment, Dauphin had low high school graduation rates, and it was common for many students to drop out at 16 to work on farms or in factories. However, by 1976, all students in Dauphin were able to advance to the final grade, indicating improved educational attainment. As noted earlier, a common concern is that basic income undermines incentives to work, but this experiment’s results contradict that criticism. Over the four years, the employment status of household heads did not change, leading to the conclusion that basic income did not reduce work incentives. Meanwhile, employment fell among household members who were not the primary earners—specifically women with children and minors. Women with children, thanks to the guaranteed income, were less compelled to work while raising children and tended to take longer parental leave, and minors no longer needed to support the household and were able to attend school.

Case study: Brazil

From 2003 to 2010, the Bolsa Família program provided basic income nationwide in Brazil to about 13.6 million households. About 46.6 million people—around 22% of Brazil’s total population—received benefits. In this program, basic income was given to poor households based on means-testing. In addition to being poor, recipients had to meet conditions such as sending their children to school and ensuring they received vaccinations. The average payment per household was about $34 per month.

After the program’s introduction, the national poverty rate declined from 26.1% in 2003 to 14.1% in 2009, and the extreme poverty rate fell from 10.0% to 4.8%. The Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, decreased from 0.58 in 2003 to 0.54 in 2009. Since the program did not include a control group, we cannot confirm a causal link between the outcomes and the policy, but it is reasonable to think the program contributed to some extent.

Bolsa Família program (Photo: Senado Federal/ Flickr)[CC BY 2.0]

In addition, the city of Maricá in Brazil has been running a new basic income experiment since 2019. About 52,000 people receive about $25–$35 per month, and in April 2020 the benefit more than doubled to about $58 per month. The conditions are: having lived in Maricá for over three years and belonging to a household with income below three times Brazil’s minimum monthly wage (about $615). A distinctive feature is that the benefit is paid in the local currency “Mumbuca,” usable only within Maricá. This enables more accurate measurement of how the basic income is spent and behavioral changes after receiving it. The Mumbuca Bank that issues this currency also provides interest-free loans to citizens and local small businesses.

The funding source is revenue from oil, so the experiment is said to be implementable over the long term. The experiment has only just begun, so results are not yet available. However, with more recipients than many other experiments and the ability to measure data accurately using a local currency, its findings will undoubtedly have a major impact on the debate over basic income adoption.

Case study: Finland

Next is an experiment conducted in Finland. For two years starting in 2017, 2,000 unemployed people randomly selected nationwide received the equivalent of $670 per month. The conditions were being 25–58 years old at the start of the experiment and enrolled in minimum unemployment insurance. Recipients continued receiving payments even if they found work during the period.

Finland’s social security agency (Photo: Kotivalo/ Wikimedia Commons)[CC BY-SA 4.0]

What results emerged from this experiment? It was found that compared with non-recipients, basic income recipients felt happier and experienced less psychological strain and stress. Among recipients, 39% felt anxious about their economic situation, compared with 49% among those not receiving UBI, indicating a lower rate of economic anxiety among recipients. Recipients also reported increased trust in social institutions such as the government and police compared to before receiving basic income. Meanwhile, the employment status of recipients did not change, and unemployment continued.

Case study: Kenya

Since 2017, a basic income experiment has been underway in Kenya as well. In the two counties of Siaya and Bomet, it targets about 20,000 people. The experiment created four groups: one group receives the equivalent of $22.5 per month for 12 years; a second group receives $22.5 per month for two years; a third group receives a lump-sum payment equivalent to about $500; and a fourth control group receives no basic income. The experiment is ongoing.

Bomet, Kenya (Photo: Kiprotich Towett/ Wikimedia Commons)[CC BY-SA 4.0]

As of 2020, the experiment has revealed various impacts of basic income. First, across all recipient groups, the share of people experiencing hunger fell by 4.9–10.8%. Clinic visit rates fell by 2.8–4.6%, and household illness rates fell by 3.6–5.7%. Recipients were also found to be less likely to suffer from depression. In addition, compared with non-recipients, recipients were more likely to start new businesses and generate profits, indicating that BI promotes entrepreneurship. Overall, basic income appears to reduce poverty and hunger and help improve physical and mental health.

Conclusion

All the foregoing examples were experimental and small in scale, so it remains unclear what effects would appear if UBI were implemented nationwide. Many examples also set relatively modest benefit levels, and it is unknown what would happen if basic income were raised to an amount sufficient to live on. There is no doubt that it would require enormous costs, and how to secure funding is a major challenge. At the same time, despite such challenges and concerns, many positive results have emerged from experiments, and the especially worrisome issue of lost work motivation has not appeared to a great extent. Moreover, as many people currently face poverty—and the number is expected to grow due to the spread of COVID-19 and climate change—basic income can be considered a highly promising policy for addressing poverty. Therefore, further debate toward the wider adoption of Universal Basic Income is anticipated.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks