Since entering 2020, the spread of the novel coronavirus has grown more severe. Large numbers of infections and deaths have occurred worldwide, having a major impact on economies and on people’s lives and work. There is no doubt this situation deserves attention. However, is the novel coronavirus monopolizing media coverage? Are there not other important events and phenomena around the world that ought to be reported? From the standpoint of human lives, we constantly face other threats on the same level as, or even greater than, the novel coronavirus—how much are those being covered? Overall, is international reporting balanced? While the novel coronavirus draws attention, are we truly able to grasp the crises the world faces? And is the media fulfilling its role in preventing or preparing for upcoming pandemics like COVID-19 and other crises? This article examines how health-related crises confronting humanity are being reported.

Novel coronavirus (Photo: Pixabay [public domain])

目次

Analysis of the volume of coverage on the novel coronavirus

First, what share does coverage of the novel coronavirus account for within Japan’s international news? In this article, we analyzed one outlet each from newspapers and SNS (social media) (※1). For newspapers, we examined five months of reporting in Yomiuri Shimbun from March to July 2020. Of 4,684 international news articles nationwide, 2,742 concerned the novel coronavirus. This shows that roughly 60% of international coverage was about the novel coronavirus. In particular, the share peaked in April 2020, reaching a very high 74% of international news.

Next, for SNS, we examined five months of the LINE News Digest from March to July 2020. The LINE News Digest is a service by LINE Corporation that distributes a selection of articles from various news organizations three times a day. Of 339 international news articles, 219 concerned the novel coronavirus, accounting for about 65%. In particular, in March the share of coronavirus-related reporting was highest at 81%. In addition, we conducted a short-term review of NHK NEWS WEB. In April 2020, coverage related to the novel coronavirus accounted for 87% of all international news.

Events and phenomena overlooked due to the novel coronavirus

The above shows that coverage of the novel coronavirus has occupied a large share of international reporting over an extended period—an unusual situation in recent years. However, other crises that threaten people have been occurring around the world during the same period as the outbreak. In other words, there are stories that normally might have been reported but were crowded out by coronavirus coverage and largely overlooked.

First, consider nature-related events and phenomena. Massive swarms of desert locusts have dealt a heavy blow to agriculture in East Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East, and in March 2020 the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warned that they were creating “an unprecedented threat to food security and livelihoods.” A single swarm can number from hundreds of millions to tens of billions of insects, and these gigantic swarms consume enormous amounts of food.

It is reported that 42 million people in East Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East are facing severe food crises. In these regions, food supplies are often unstable under normal circumstances, which is a major factor. Thus, despite the desert locust upsurge threatening lives at least as much as, if not more than, the novel coronavirus, the Yomiuri Shimbun ran only 2 articles on the outbreak from March to July 2020.

Swarms of locusts in Madagascar (Photo: Iwoelbern/ Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

South Asia has also suffered major damage from cyclones. In May 2020, the most intense cyclone since 1999 struck Bangladesh and India. It reportedly killed at least 106 people. More than 3 million people were forced to evacuate. Such cyclones are clearly a threat to human life, yet from May to July 2020 the Yomiuri Shimbun carried no related reports.

The threats are not only from nature. A cross-border armed conflict in the Sahel region of West Africa has created a major humanitarian crisis in countries such as Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. In Burkina Faso, which had relatively little experience of conflict, about 3.3 million people are facing severe food insecurity, with conflict a contributing factor. Since 2018, increased activity by armed groups has worsened security, leading to rising forced displacement and deteriorating domestic food supplies. In 2020 alone, there were about 500,000 newly displaced persons, with the cumulative number reaching about 920,000. Nevertheless, from March to July 2020, the Yomiuri Shimbun ran no coverage related to this issue.

Existing health crises

Deaths from the novel coronavirus since its emergence in December 2019 totaled 840,000 by the end of August 2020, posing a major threat to human life. The impact on the world is substantial, prompting fear and concern—and certainly deserving of attention. However, beyond the novel coronavirus, many other dangerous diseases routinely claim large numbers of lives worldwide. Is the media reporting these at a scale commensurate with their magnitude in normal times? To explore this, we examined Yomiuri Shimbun data from fiscal year 2019, prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

First to note is pollution, a leading cause of death globally. In 2015 alone, roughly 9 million people worldwide died from pollution-related causes. Of these, about 6.5 million died from respiratory and other illnesses caused by air pollution, about 1.8 million died from diarrheal and other diseases caused by water pollution, and nearly 1 million died from workplace-related pollution. Yet in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s international coverage over the course of 2019, only 2 articles mentioned pollution as a threat to human life.

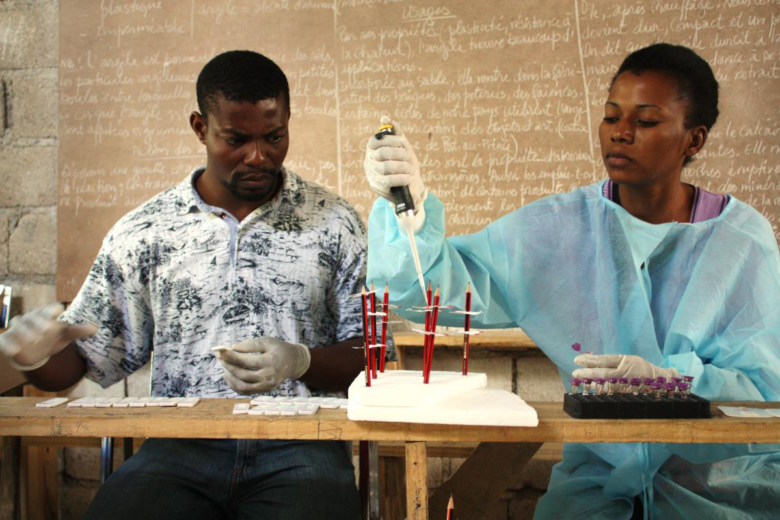

What about infectious diseases other than the novel coronavirus? Tuberculosis kills about 1.5 million people per year (※2). Diseases related to HIV/AIDS kill about 690,000 people annually (※3). Respiratory diseases linked to seasonal influenza kill up to 650,000 people each year. And worldwide, 440,000 people die from malaria annually (※4). Nevertheless, in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s international reporting in 2019, there were only 4 articles on the threat to human life from tuberculosis, 1 on HIV/AIDS, 1 on seasonal influenza, and 2 on malaria. These diseases have treatments and preventive measures, yet many people continue to die.

Conducting a malaria test (Photo: CDC Global/Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Why are such large-scale health crises so rarely reported? Why is there such a stark difference in volume compared to coverage of the novel coronavirus? One reason is likely that the number of victims in Japan is extremely small. In addition, many victims of these health crises are in low-income countries. This highlights a problem with the media, namely the difficulty of getting issues in low-income countries reported. Another reason is the media’s tendency to focus on “new” crises. Even though the number of people suffering from the above crises is greater than, or comparable to, the number of COVID-19 victims, they are treated as if the situation were “normal” and receive little coverage. Moreover, much remains unknown about the nature and treatments of the novel coronavirus. Uncertainty about how far infections will spread and how many lives may be lost fuels fear and interest, drawing more attention. In short, the pure threat to human life is not what is guiding editorial decisions.

Health crises to come

Major health crises like those above are constantly occurring. Some can be prevented to a certain extent, but their impacts are already visible and are expected to grow. Unlike malaria and pollution, these are also likely to have significant impacts within Japan. One such crisis is that caused by climate change. Health risks from climate change are already becoming severe. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2020 has a high probability—75%—of being the hottest year globally since records began. In this context, impacts from rising temperatures are increasing. Around the world, among outdoor workers in agriculture and construction, health harms such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke and kidney disease are on the rise.

Rising temperatures are expected to have increasingly severe effects. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), if temperatures rise by 3 degrees by the end of this century, an additional 73 people per 100,000 will die due to heat. If global warming continues, outdoor temperatures may become unbearable for humans and deadly for crops. As a result, food supplies could become difficult, raising the risk of global famine, it has been pointed out.

Other impacts of rising temperatures include sea-level rise and extreme weather. These cause flooding, and floods in turn trigger outbreaks of infectious disease and are a growing concern. By the end of the 21st century, extreme precipitation events are projected to increase with warming, reaching up to 3 times the historical average. Therefore, floods and the infectious diseases they trigger—caused by rising temperatures—constitute emerging threats to human life.

Flooding (Photo: PranongCreative/Needpix.com [public domain])

However, as GNV noted in a previous article, “Are the media aware of the planet’s crisis?,” in the first half of 2019 Asahi Shimbun ran only 16 articles with climate-related keywords in the title. And even though NHK participated as a partner in the “Covering Climate Now” initiative, over the one-month period including the April 2020 campaign, it aired only one climate-related news item. Thus, the existing media are far from providing coverage—either in volume or substance—commensurate with the threat climate change poses now and will pose even more seriously in the future.

Another health crisis expected to become more severe is the problem of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial resistance refers to bacteria and viruses developing resistance to drugs such as antibiotics used to treat the diseases they cause, rendering these drugs ineffective or less effective. In other words, even when treatments exist, increasing resistance can render drugs that should work ineffective, leading to death. Astonishingly, it is estimated that antimicrobial resistance currently kills about 700,000 people each year, already a major health crisis. Moreover, a UK government report in 2014 projected that by 2050, antimicrobial resistance could cause annual deaths of 10 million worldwide.

Antibiotics (Photo: oliver.dodd/Flickr)[CC BY 2.0]

Why is antimicrobial resistance worsening? It is driven by the overuse of antibiotics and other antimicrobial drugs in humans and livestock. The problem has deepened further amid treatment of COVID-19 patients. Currently, antibiotics and antimicrobial drugs are being used at very high rates as part of COVID-19 treatment and prevention, increasing resistance. In addition, pharmaceutical companies have been neglecting the development of new antibiotics and antimicrobials because they see little profit in it. And because society at large is not focused on antimicrobial resistance, responses have been delayed. Despite its potential to become an even more serious threat to human life, the Yomiuri Shimbun’s international coverage in 2019 contained no articles addressing antimicrobial resistance.

Infectious diseases in the long view

It is important that the novel coronavirus, a global problem, be covered extensively. But the emergence of such novel infectious diseases is not unprecedented and occurs every few years—for example, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2003. Moreover, the incidence of infectious disease outbreaks has been steadily increasing. To prevent the emergence and spread of infectious diseases—and to respond once they occur—we need to focus on their risks before outbreaks happen and share and debate information ranging from preventive measures to post-outbreak responses. From this perspective, the media have a major role to play. So how can we prevent emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19?

One factor in the emergence and spread of infectious diseases is environmental destruction and deforestation. These processes facilitate outbreaks over the long term. Comparing degraded areas to intact ones, the populations of animal species that harbor zoonotic diseases were found to be up to 2.5 times higher. Zoonoses are infections, like the novel coronavirus, in which a pathogen reproduces in an animal host and then infects humans. Furthermore, comparing degraded ecosystems to intact ones, the share of species that carry disease pathogens increased by up to 70%. In short, the more nature is destroyed, the more animals that harbor infectious diseases—and vectors that carry pathogens—will increase.

Deforestation (Photo: TFoxFoto/Shutterstock)

Deforestation also increases opportunities for contact with wild animals that carry viruses, raising the likelihood that zoonoses will infect humans. For example, a 2019 study found that a 10% increase in forest loss led to a 3.3% increase in malaria cases—equivalent to 7.4 million people worldwide. Deforestation is also associated with 31% of outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Ebola, Zika, and Nipah virus. Moreover, because many drugs and vaccines originate in nature, the loss of biodiversity from environmental destruction makes the development and production of medicines and vaccines more difficult.

Nevertheless, since 2016, an average of 28 million hectares of forest have been lost annually, with no sign of decline. If this continues, emerging infectious diseases will recur and cause suffering. Conversely, reducing environmental destruction and deforestation can help prevent outbreaks over the long term. Economically, it is estimated that with just 2% of the economic losses caused by the COVID-19 crisis, we could prevent major pandemics over the next 10 years. Yet in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s international coverage over 2019, only one article addressed deforestation.

Another driver of emerging infectious diseases is the livestock industry. About 60% of existing infectious diseases and about 75% of emerging ones are zoonotic, and roughly 2 million people die from zoonoses each year. The livestock industry carries high risks for the emergence and spread of zoonoses due to intensive animal management and the overuse of antibiotics and antimicrobials that strengthens resistance, it has been noted. In addition, particularly for cattle grazing and feed production, further deforestation is advancing, contributing to the emergence and spread of diseases via the mechanisms described above. Thus, if the status quo continues, the livestock industry may increasingly cause zoonotic outbreaks. In response, by reducing our meat consumption and shrinking the livestock industry, we can help prevent the emergence and spread of zoonoses. However, in 2019 the Yomiuri Shimbun ran no international coverage pointing out the threats posed by the livestock industry.

Pigs in livestock farming (Photo: PxHere [public domain])

Beyond environmental destruction, deforestation, and the livestock industry, global warming also raises the risk of emerging infectious diseases. For instance, global warming can thaw permafrost soils, releasing ancient viruses and bacteria that may infect humans. Permafrost is cold, anoxic, and dark—conditions that preserve microorganisms and viruses for long periods. It has been suggested that pathogenic viruses with the potential to infect humans and animals—including those that caused past pandemics—may be preserved in permafrost layers. For example, in 2016, one person died and at least 20 people were hospitalized after exposure to anthrax released from thawing permafrost on the Yamal Peninsula in the Arctic.

As Arctic sea ice melts and access to the Siberian Arctic coast becomes easier, industrial development such as mining for gold and minerals and drilling for oil and natural gas has become more profitable. At present, these regions are uninhabited and the permafrost remains intact. However, permafrost may be exposed by extraction activities. If pathogenic microorganisms or viruses are present there, there is a risk of disease emergence and spread, it is said.

Thus, global warming is a threat to human life. Yet in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s coverage over 2019, there were no articles pointing out the threat of infectious disease emergence due to permafrost thaw. And as noted above, media coverage related to climate change is far from sufficient in both volume and substance.

Toward improving international news coverage

In sum, allowing the immediate crisis of the novel coronavirus to monopolize coverage makes it difficult to grasp other ongoing health crises. Rather than concentrating reporting only while a crisis is unfolding, the media must adopt a long-term perspective to prepare for similar health crises to come. If we continue as we are, humanity will suffer even more from infectious diseases in the future. However, by taking a long view of the world’s situation and acting accordingly, we can prevent or mitigate crises like the novel coronavirus. Had we long recognized and acted on threats to humanity, the damage from the novel coronavirus might not have been so great. It is urgent that the media reassess their role.

※1 This article analyzes only the volume of coronavirus coverage, not its content or geographic distribution. The analysis is limited to international reporting set outside Japan.

※2 Data for 2019.

※3 Data for 2019.

※4 Data for 2017.

Writer: Ikumi Arata

Graphics: Yumi Ariyoshi

新型コロナウイルス関連の記事が多いというのは実感していましたが、その影には大きな問題も多数隠れていると知り衝撃でした。改めてメディアに対して、速報のものだけでなく、長期的な視点で情報を伝えていってほしいと思いました。

サバクトビバッタの大量発生やサイクロンは大々的に扱われてもおかしくないほどのニュースなのに、メディアで見たことがなく、恥ずかしながら知らなかった。とても勉強になったし、自分でもコロナ以外のニュースに目を向けてみようと思った。