In December 2013, Uruguay legalized the use and commercialization of cannabis (Note 1). The decision faced opposition from some citizens and, because it ran counter to existing international agreements, it was controversial at times. With this move, Uruguay became the first country in history to permit the use of cannabis, paving the way for other nations to follow. This article examines how legalization began and progressed in Uruguay, and what effects it has had domestically since its adoption.

Cannabis sativa (marijuana plant) (Photo: Lode Van de Velde / PublicDomainPictures.net [CC0 1.0])

目次

Decision

Uruguay has long been less strict than many other countries regarding drug use. During the civilian–military dictatorship (Note 2), while drug trafficking was considered a crime, possession of small quantities of illegal drugs for personal use was not criminalized. Thus, under the law, cannabis users could possess small amounts, but there was no legal way to obtain it.

The situation changed in 2012 when President José Mujica of the ruling Broad Front announced his intention to approve a law that, under direct government control, would allow not only home cultivation of cannabis plants but also direct public sales. Officials in charge at the time argued that legalization, by depriving drug traffickers of income, would improve public security in Uruguay. It was also believed that if citizens could legally produce or obtain cannabis with guaranteed quality, there would be positive effects for safety and health. The bill was also seen as a way to end two persistent inconsistencies. First, the fact that possession of cannabis was legal while its sale was illegal. Second, while alcohol and tobacco, which are more addictive and harmful than cannabis, were ultimately legal, cannabis remained illegal.

The policy was immediately criticized both inside and outside Uruguay. A majority of citizens initially opposed the bill. Concerns arose about health issues (particularly among young people) and the possibility that drug use would lead to increased violence and crime. There were also worries that, as in the Netherlands, foreign tourists would visit Uruguay to use cannabis. Internationally, Uruguay was criticized as well, with the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) (Note 3) arguing that the new law violated international treaties. Nevertheless, Uruguay maintained that its decision was justified, countering that the bill would contribute to the government’s primary duty of protecting citizens’ human rights.

Amid ongoing debate, the Uruguayan government finally approved a law legalizing cannabis use in December 2013. The law established regulations for cultivating and using cannabis plants via three distinct modalities. Users could select only one of the following modalities:

1) Sales: individuals can obtain up to 40 grams per month.

2) Cannabis clubs: groups of 15–45 people may cultivate cannabis and distribute up to 480 grams per member per year; any surplus must be delivered to the authorities.

3) Home cultivation: individuals may grow up to six female plants. In the case of a cannabis club, an individual may produce up to 480 grams per authorized year.

To dispel concerns that foreign tourists would come to use cannabis, only Uruguayan citizens could register for one of the three modalities above. In other words, foreigners could not legally obtain cannabis in Uruguay. Other restrictions were also set, such as bans on driving under the influence of cannabis and on use in the workplace. To regulate the different modalities and uses and to facilitate coordination among government bodies, the Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis (IRCCA) was established, which also handled consumer registration.

Implementation

Despite the initial debate and some public opposition to the new law, it appears not to have become a major public issue, perhaps because it had little tangible impact on daily life. This was borne out by the victory of the Broad Front, the party that advanced the bill, in the subsequent 2014 general election, and surveys indicate that since 2013 public interest in the issue has waned.

Former President José Mujica (Photo: Frente a Aratiri / Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Because it took time to resolve technical issues and bureaucratic aspects, full implementation of the law took years. In 2014 the government began registering cannabis clubs and home growers and started applying the new regulations. There were also various problems due to limited understanding of the law’s details among the police and others, including mistaken detentions stemming from confusion between male and female plants. However, such issues gradually decreased. As of February 2020, registered users included 40,563 pharmacy purchasers, 8,141 individual home growers, and 158 cannabis clubs with 4,690 members.

It took time to implement direct supply to the public through pharmacies. This was only achieved in 2015 when the government selected two companies to produce cannabis and distribute it to pharmacies for sale to end consumers: International Cannabis Corporation (ICC) and Symbiosis. Production began in 2016, but retail sales were delayed because the IRCCA was still refining consumer registration and verification methods, and because some of the first cannabis produced by Symbiosis did not meet the government’s technical requirements. In July 2017, registered users finally became able to legally purchase cannabis at pharmacies.

However, another obstacle arose: with only a handful of exceptions, pharmacies could not sell cannabis-related products. Many Uruguayan pharmacies depended on U.S. banks, or on Uruguayan banks that in turn depended on U.S. banks. Those U.S. institutions argued that involvement in any activity related to the commercialization of drugs, including cannabis, would run contrary to national policy. As a result, pharmacies selling cannabis were forced to choose between switching to cash-only business practices or ceasing in-store cannabis sales. This progressively limited the number of outlets stocking the product or handling distribution in certain areas. As of June 2018, 11 of Uruguay’s 19 departments had no pharmacies offering cannabis, and at the time of writing only 17 stores provided cannabis over the counter, with the government considering creating dispensaries to meet demand.

At the same time, not only were there few points of sale, but legal production was limited to two companies, posing challenges in meeting government requirements. This led to delays in the process, shortages relative to demand, and queues of customers seeking to purchase the product. To meet demand, in 2019 the government selected three additional companies and authorized them to produce recreational cannabis for pharmaceutical distribution.

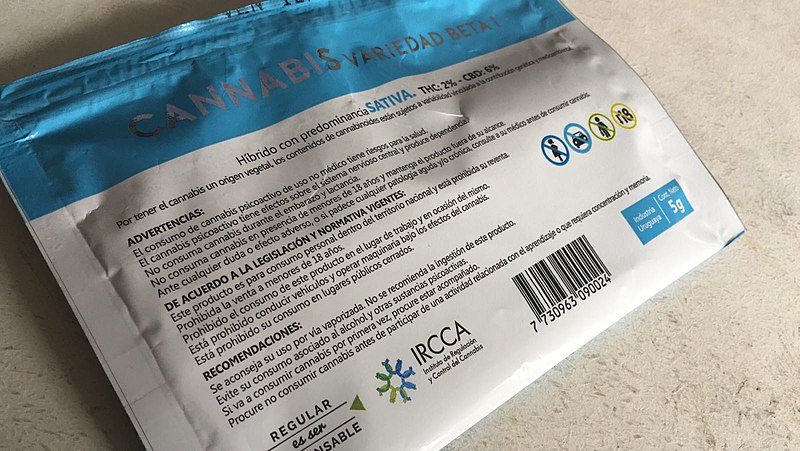

Cannabis sold in Uruguay (5 g) (Photo: maurirope / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Impacts so far

We examine the effects of cannabis legalization through the lenses of crime, consumption, the economy, and cannabis tourism.

Regarding crime, cannabis is only one of many factors associated with criminal behavior, and its influence is not necessarily direct, making it difficult to identify a direct relationship between cannabis use and crime trends. However, it was noted that national crime rates fell in 2016 and 2017. Supporters of the law quickly pointed to this as evidence of its positive effects. Yet crime increased in 2018 and 2019. In response, Interior Minister Eduardo Bonomi and others stated that a reduction in criminal proceeds due to legalization had intensified violent conflicts among gangs and mafias. Juan Andrés Roballo, Secretary of the Presidency, estimated the loss of illegal revenue at $10 million over a year and a half. According to the National Drug Board, 58% of cannabis users obtained the drug illegally in 2014, but by 2018 that number had fallen to 18%, indicating a shift from the black market to the legal market.

Another concern regarding legalization was that youth use would increase and the age of first use would fall. However, the 7th National Survey on drug use among secondary school students found no change in cannabis use rates. Moreover, the 8th National Survey on drug use in the general population showed that the average age of first cannabis use rose from around 18 in 2011 to 20 in 2018. This trend contrasts with alcohol and tobacco, which are considered more harmful to individual and social health than cannabis. As of 2018, 72% of Uruguayan secondary students had consumed alcohol, and 20% had used cannabis. The average age at which Uruguayans begin drinking is 16.8.

As for economic effects, in addition to shifting revenue from the black market to the state through domestic demand, legalization also created jobs related to the cannabis production process. Furthermore, multinational companies have shown interest in cultivating cannabis in Uruguay not only for Uruguayans but also for medical use abroad. This could create more jobs and generate additional revenue for Uruguay’s economy.

Finally, consider cannabis tourism. The law legalized access for Uruguayan citizens and excluded tourists. However, new gray areas have emerged whereby legally produced cannabis is sold to tourists via methods not covered by the current law. As detailed regulations on cannabis use and commercialization continue to be developed, the government is likely to take further measures to address this.

The Parliament building of Uruguay (Photo: Gabboe / Wikimedia [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Overall, Uruguay’s experience represents the world’s first national-level experiment in cannabis regulation, implemented over time with ongoing regulatory adjustments. So far, there is no evidence of increased harm to society as a whole. Consumers can obtain products more safely and legally, authorities maintain strict oversight to prevent problems, and businesses and the government benefit. Whether cannabis legalization can be called a success will depend on the passage of time and how the government continues to adjust implementation. If deemed successful, similar bills may be advanced in other parts of the world.

Note 1: According to Sanseido’s Daijirin, Third Edition, cannabis is “dried leaves and inflorescences of hemp; also its resin. Smoking produces psychoactive effects such as a sense of liberation.” It may be used for medical, recreational, or religious reasons. It is also known as marijuana and hashish.

Note 2: “Civilian–military” means the state’s top figure is a civilian head of the military and, in practice, holds no real power.

Note 3: The INCB oversees implementation of the UN drug conventions, which stipulate that drugs such as cannabis may be produced and distributed only for medical or scientific purposes.

Writer: Elisabet Vergara Velasco

Translation: Saya Miura

Graphics: Saki Takeuchi

大麻の合法化イコール失敗というイメージだったため、ウルグアイの事例は意外だった。今後の動向に注目したいと思います。