Inequality is widening across the world, and the concentration of wealth has reached an extraordinary level. Currently, the wealthiest 20 percent of the world’s population monopolize 94.5 percent of global wealth. It has also been revealed that the eight richest people in the world own the same wealth as 3.6 billion people—the poorest half of the global population. Why, then, is such inequality not narrowing? In discussions about escaping poverty in the least developed and developing countries, terms like “development assistance,” “international cooperation,” and “international contribution” fly around in advanced economies. But does this perspective capture the essence of the problem? To begin with, development assistance from advanced countries is woefully insufficient. The aid provided by economic powers such as the United States and Japan remains at less than one-third of the UN target (0.7% of GNI). Moreover, within that development assistance, not a small amount of “aid money” returns to donor countries in the form of costs for projects carried out by their own companies (especially infrastructure support) and consulting fees.

Photo: Issarawat Tattong / Shutterstock.com

There is also a much bigger problem lurking that hinders poverty reduction. Trade and investment are essential to achieving sustainable development—so much so that the adage “trade not aid” is often invoked. It would be ideal if trade created a win-win situation for both sellers and buyers, but in reality, significant profits are illicitly flowing out of the least developed and developing countries through trade. Many companies operating in these countries are believed to use various illegal methods to minimize taxes. For firms exporting natural resources or products, common tactics include inflating extraction or production costs, or understating export prices, to make profits appear lower.

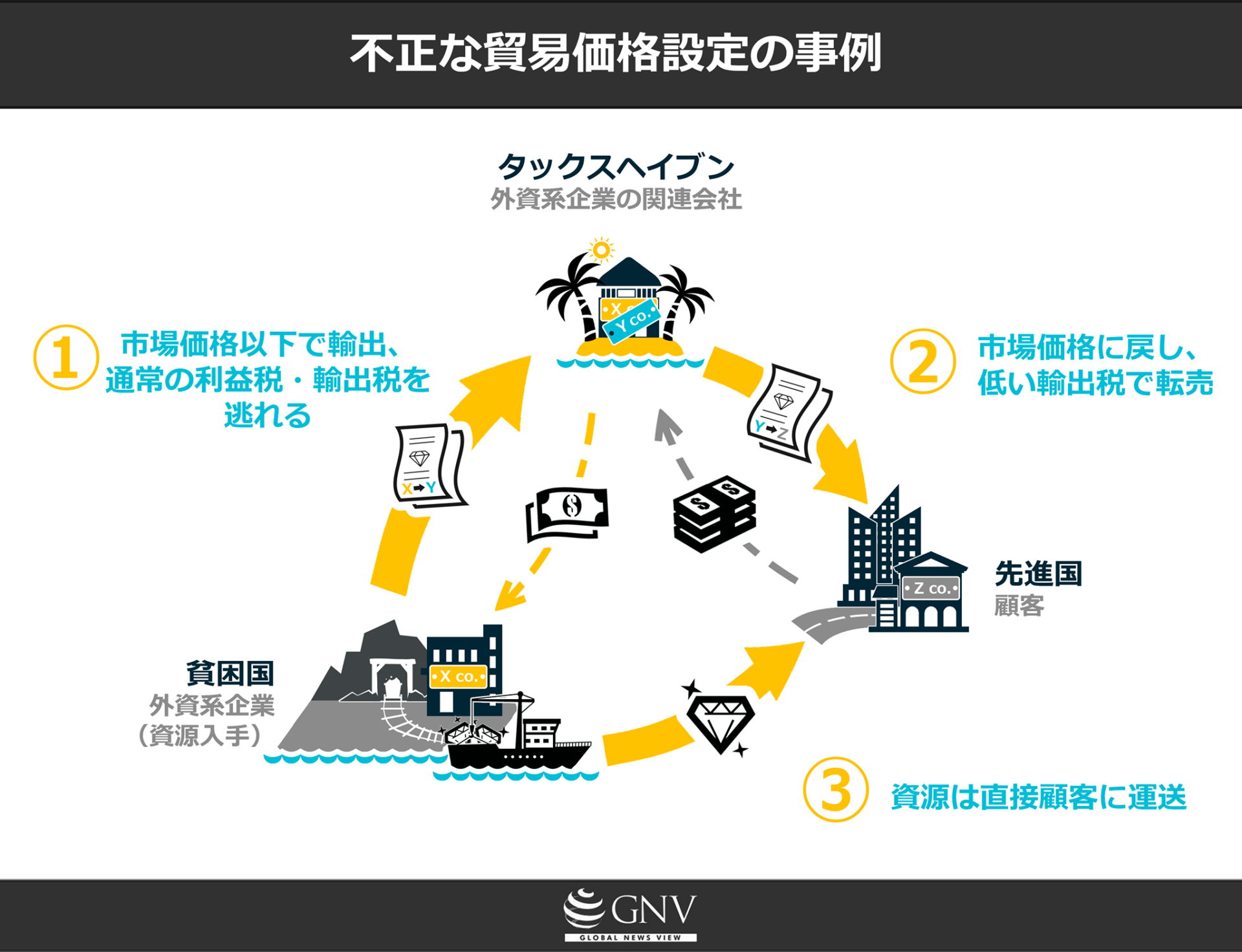

Against this backdrop, trade mispricing and trade misinvoicing stand out. For example, when a foreign company that mines mineral resources in a poor country exports those minerals, it first “sells” them at a price far below market value to an affiliated company located in a low-tax jurisdiction (a tax haven) to avoid paying profit taxes and export duties in the poor country. Next, the affiliate in the tax haven “resells” the minerals to the actual customer in a developed country at the proper price. The minerals themselves do not physically pass through the tax haven; they are shipped directly from the poor country to the customer. To conceal the fact that the company in the tax haven is an affiliate, multiple shell companies are often set up and complex corporate relationships are created. The Panama Papers leaked from a Panamanian law firm in 2016 exposed parts of these mechanisms.

Poor countries suffering damage often cannot marshal the budgets and personnel (such as international lawyers) needed to police such outflows, and in some cases insiders within government collude with foreign companies in exchange for financial kickbacks. Illicit financial flows are often thought to be the work of a limited number of “bad” companies, but the total losses indicate just how widespread these tactics are and how serious the problem is. For example, it has been reported that the profits earned by U.S. multinationals in Bermuda—a small set of islands with a population of 70,000—exceed the combined profits they earn in Japan, China, Germany, and France.

Mailboxes in the Cayman Islands, where many shell companies are based (Pixabay)

However, illicit financial flows are not just a matter of trade mispricing. In fact, even when trade prices are manipulated, the transactions still go through formal channels, and tax evasion is carried out by manipulating official prices. There is also the problem of smuggling—trade via informal routes that completely bypass tariffs. This is more the domain of criminal organizations than foreign corporations. Furthermore, another pattern of illicit financial flows involves government officials in poor countries embezzling state funds or accepting bribes from foreign companies and stashing the money in banks abroad. According to Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a private organization that analyzes illicit financial flows, roughly 60–65% of IFFs from Africa stem from trade mispricing, 30–35% from activities by criminal organizations such as smuggling, and about 3% from embezzlement and similar abuses by government officials.

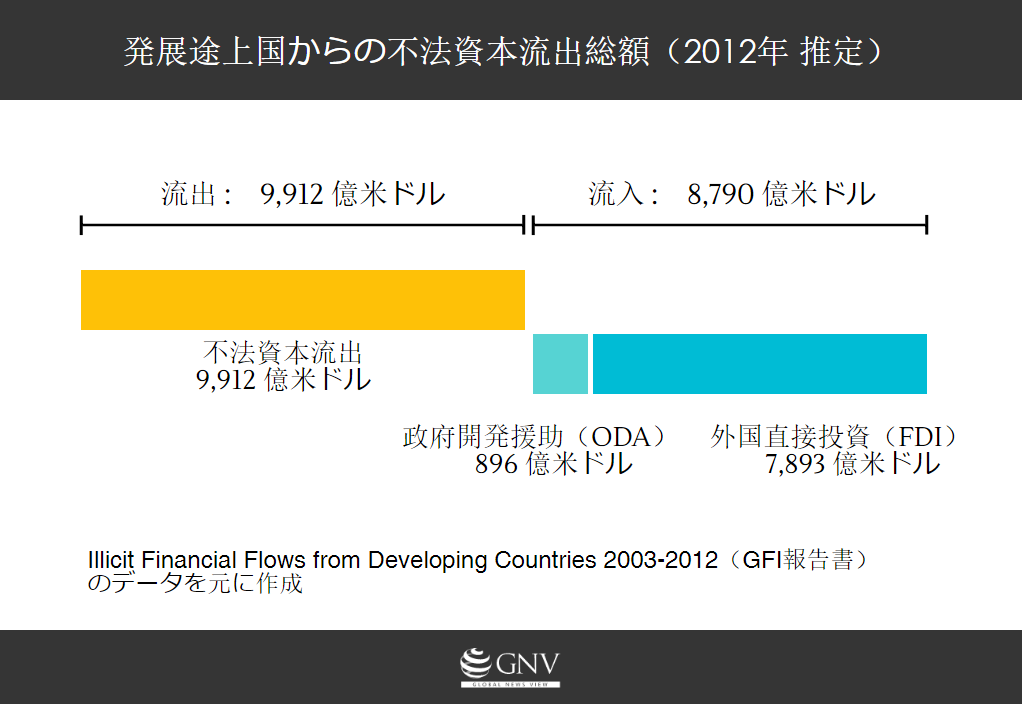

From these circumstances, it is clear that illicit financial outflows from the least developed and developing countries amount to staggering sums. As shown in the figure below, the amount is more than ten times total ODA, and even ODA combined with foreign direct investment (FDI) falls short of illicit outflows. Currently, the total value of these illicit outflows exceeds US$1 trillion per year.

So where does this money go? Much of it of course passes through—or remains in—tax havens such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and Switzerland. However, according to GFI, as much as 67% of illicit financial flows end up in banks in the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

The figures above refer only to illicit financial flows, but the shadow of legal yet unfair trade also looms large in hindering development in the least developed and developing countries. In other words, weaker countries—and their local companies, workers, and farmers—often sell resources, goods, and labor at extremely low prices to major powers and large multinationals that hold overwhelming bargaining power. This pattern is seen from interstate trade agreements to contract farming at the individual level. Unfair though it may be, it remains legal.

To consider poverty reduction, we need to take into account an even more comprehensive “balance.” In addition to aid, FDI, and illicit outflows, if we tally all flows including trade (both fair and unfair), borrowing, debt service, deposits in overseas banks, and remittances from migrant workers, we can get some sense of whether prospects for escaping poverty are realistic. A study that applied these indicators to 33 Sub-Saharan African countries found that during 1970–2008, more capital flowed out of Sub-Saharan Africa than flowed in. In aggregate, then, the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa are net creditors to the world. From this perspective, it is not at all surprising—indeed, one might say it is the natural outcome—that rather than achieving poverty reduction in regions like Africa, the gap in wealth between them and advanced and other major powers is widening.

The oil industry, where illicit financial flows are frequently reported. Photo: curraheeshutter/ Shutterstock.com

So, are measures to address illicit financial flows making progress? Unfortunately, there has been no significant improvement. At the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD3), held in Ethiopia in 2015, institutional reforms at the level of international organizations were placed on the agenda and discussed. The United Nations has a “Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters” that considers issues such as illicit financial flows, and the least developed and developing countries strongly called for upgrading this committee into a formal international body. However, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, and others strongly opposed the move, and it was not realized.

In such circumstances, can we put the brakes on the widening inequality at the global level?

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Graphics: Kamil Hamidov

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks