In most countries, media organizations are monopolized by large corporations, and the journalism carried out there is part of a profit-driven business. Governments also play a major role in the production and distribution of news through what are called state and public media.

However, whether such media can provide people with unbiased information about their own country and the world is often questioned. This is of particular concern given the declining levels of media diversity and media freedom around the world. In many countries, over the past few decades, mergers and acquisitions have led news operations to become increasingly concentrated in the hands of fewer companies. In addition, recent years have seen a rise in the level of political influence over the media.

Amid such trends, there is a lesser-noticed third group among media actors. This group is considered less susceptible to commercial interests or state power and is known as “independent media.” They exist around the world, though their scale is relatively small. They operate through newspapers and magazines, community radio stations and podcasts, online media, and channels on social media.

Given the troubling trends mentioned above, outlets like independent media are playing an increasingly important role in the information environment provided by journalism. What are independent media, and what challenges do they face? That is the subject of this article.

A journalist in electronic media, Pakistan (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

目次

Definition of independent media

Independent media are generally seen as distinct from commercial media and state/public media, but a clear definition is not necessarily simple. In principle, independent media are those that do not bow to profit or state power, but what this actually means is not always clear. The question is what characteristics guarantee the independence of a media organization.

For some, the distinction is clear. Borrowing the words of staff at a U.S.-based nonprofit newsroom, it means “no ads, no paywalls, no corporate or government funding.” This definition suggests that independent media are a type of nonprofit organization. The revenue needed to sustain the organization may come from subscriptions and donations from readers and audiences, or via fundraising activities not directly related to reporting.

At the same time, there are many outlets that act as watchdogs—monitoring and criticizing state power—and are called “independent media” by others, yet rely on advertising revenue and shareholder investment. The Indian online outlet NewsClick(Newsclick), the Philippines’ Rappler(Rappler), and the now-defunct Zambian newspaper The Post(The Post) are examples. Such outlets may establish strict rules and internal agreements aimed at preventing profit-seeking as a business from influencing editorial content.

Conversely, there are commercial media that choose to call themselves “independent media” even though they are not independent in practice. With trust in media declining in many countries, calling themselves “independent” may be an attempt to burnish their reputation—used as part of branding to gain trust purposes.

An independent newspaper published in the United States during the Vietnam War, Quicksilver Times (Photo: Washington Area Spark / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

It should also be noted that being independent does not necessarily mean being impartial or nonpartisan. Reporting is inevitably produced from someone’s point of view; true objectivity and neutrality do not exist. Even so, freedom from corporate and state influence is considered the key to independence in journalism.

Another related term often used to describe independent media is “alternative media” (alternative media: alternative media). This is generally used to distinguish them from so-called “mainstream media” run by large corporations or the state. Strictly speaking, this distinction is less about independence and more about the degree of monopoly in the information environment—seeing these outlets as having less reach than the mainstream that most of the general public consumes. It also suggests that these outlets offer different kinds of content or perspectives than those provided by commercial or state media.

The importance of independent media

It is said that 80% of the world’s population lives in countries without press freedom. In such countries, journalism that challenges the powerful and the wealthy is extremely difficult and often dangerous. Journalists may face risks of violence and arrest, and outlets may be shut down. But what about media in countries said to guarantee “press freedom”?

Where “press freedom” exists, media run by corporations or by the government (or government-related entities) can, in principle, carry out reporting independent of those influences. For example, in commercial media, the separation of departments that handle sales and advertising from those that handle reporting and editorial activity has long been a basic principle. In public media as well, editorial independence is often secured, at least on paper. For instance, the BBC’s charter in the United Kingdom guarantees editorial independence from the government.

Journalists taking photos at an International Monetary Fund and World Bank meeting, Japan (Photo: World Bank Photo Collection / Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0])

In reality, however, things are different. In recent years, for example, the principle of separating commercial and editorial operations has been increasingly undermined in commercial media, and profitability is often prioritized over the public interest. Pageviews, clicks, and whether advertisers’ interests are served are becoming decisive factors in whether an event becomes “news.” In state and public broadcasting, government influence also appears unavoidable. Although the BBC’s independence is guaranteed in its charter, in practice the UK government wields significant influence over the BBC.

Whether state/public or commercial, in the so-called mainstream there is a clear tendency to side with concentrations of power and wealth. Coverage places heavy focus on the actions and interests of political and economic elites, relying heavily on their official announcements rather than on original investigation. For example, when their own government seeks to wage war on another country (cases), or when it favors the continuation of wars elsewhere (cases), media rarely question it or explore peaceful alternatives. Even propaganda and disinformation disseminated by their own governments or powerful allies are often reported without scrutiny.

Furthermore, when media ownership is concentrated in fewer companies, content becomes more homogenized, and as media move closer to power and wealth, the range of perspectives and content tends to narrow. Some even argue that to assume “press freedom” exists simply because a country is a democracy is an illusion. For factors behind state and corporate influence over media, see GNV’s article.

Regarding international news, there are major problems with the coverage provided by state/public and commercial media. First, there is little international reporting itself, and the amount of international coverage by commercial media has declined over the past few decades. Second, there is a large imbalance in content. Media rarely cover phenomena that prevail across most of the world. As GNV has frequently pointed out, in Japan’s media, for example, most international coverage focuses on high-income countries or countries prioritized by the Japanese government and corporations. Major global trends—such as the sharp increase in global inequality since the COVID-19 pandemic—remain largely unreported in Japan’s major media. There also appears to be little interest in corporate scandals involving Japanese companies overseas, which are rarely covered.

Iraqi and U.S. military officials hold a press conference, Iraq (Photo: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff / Flickr [CC BY 2.0])

Such trends are seen worldwide. Overall, international coverage is dominated by the priorities of wealthy countries and their governments. These problems in the global information environment were flagged in UN committees in the 1970s and 1980s, yet persist today. Governments’ actions also affect media in other countries. Many governments, for instance, hire PR firms to try to influence foreign media to portray their country and government favorably. Even official development assistance (ODA) can shape media coverage: there are observations that ODA projects are reported positively in recipient countries without critical scrutiny by local media.

Considering this, there is a strong need for media that can operate independently of government and corporate interests. Moreover, even as globalization advances and our connections to the world deepen like never before, the decline in international coverage in mainstream media is problematic—another area where independent media have a role to play.

Funding challenges

Independent media have existed for a long time and have found ways to sustain themselves without funding from governments or corporations. A prominent example of globally minded independent media is the UK-based magazine New Internationalist(New Internationalist). Launched in the 1970s by a nonprofit engaged in international aid, it was created out of concern that commercial media would not cover low-income countries or global issues facing humanity. Today, it is a cooperative owned by its staff and 4,600 readers.

The rise of the internet has greatly contributed to the development of independent media. Traditionally, running a media outlet required major printing presses and distribution networks for newspapers and magazines, or broadcasting equipment and antenna networks for broadcast media—all of which required substantial investment, meaning involvement from governments or large corporations. The internet changed this. Small independent media organizations can now distribute text, audio, and video to large audiences easily and at low cost online.

New Internationalist’s Australia office (left), 2015 cover (right) (Photos: Singhmon (left) NewInt (right) / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain (left) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (right)])

While gathering information—the raw material of reporting—still entails significant costs, especially when deploying reporters on the ground, advances in the internet and other ICTs have made remote newsgathering easier. Overall, these technologies hold great potential for the development of independent media.

At the same time, the rise of the internet has brought many challenges for independent media. They often rely on subscriptions and donations from readers and audiences to fund their operations. However, the spread of online news seems to have reduced people’s willingness to pay for journalism. A survey of 20 countries in 2024 found that, on average, only 17% of online news users pay in some form, such as subscriptions. Japan was on the low end at just 9%.

Similarly, the rise of tech companies such as social media platforms has brought both opportunities and challenges for independent media. Many independent outlets are heavily dependent on search engines (primarily Google) and social media platforms for audience discovery.

However, search engines and social media platforms monopolize most of the advertising revenue generated by the viewing of such content, and little is returned to the outlets that provide it. These tech companies can also control whether online content reaches audiences. They sometimes change platform algorithms to reduce the amount of news shown to users. In more targeted cases, platforms intentionally lower the visibility of particular sites through what is called a shadow ban. Such actions may also be taken at the request of their own governments.

Some independent media depend on funding from wealthy donors who support their vision and editorial stance. The U.S.-based ProPublica(ProPublica) is one such outlet, initially established by a single wealthy donor. It quickly became known for critical reporting on organizations and individuals with concentrated wealth and power. However, relying on wealthy donors carries risks. If donor funding is short-term, sustainability suffers. There is also the danger that donors may use their position to try to influence editorial content and priorities.

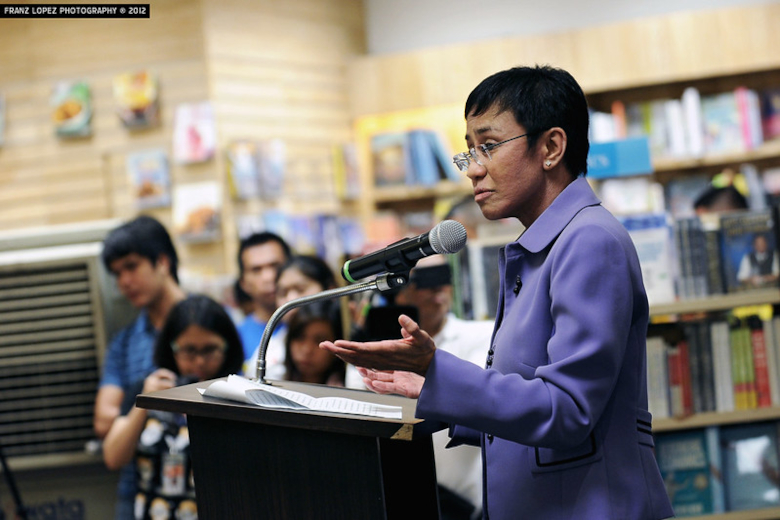

Rappler founder Maria Ressa (Photo: Franz Lopez / Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0])

Some independent outlets have set internal rules to manage such risks. For example, the South Africa–based investigative nonprofit amaBhungane(amaBhungane) limits the share of funding from any single donor to 20% of its total budget.

The future of independent media

As seen above, the challenges facing independent media are significant. Yet as independent media continue to develop around the world, support for them is also growing. UNESCO, for instance, has begun providing grants to support the development of independent media in low-income countries. In 2022, another fund—the International Fund for Public Interest Media—was established for a similar purpose. In addition, nonprofits such as International Media Support(IMS) and Reporter Shield(Reporter Shield), which supports the legal protection of independent media, are working to support these organizations’ activities.

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) guarantees everyone the freedom “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Goal 16 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also includes a target to ensure “public access to information.” Media should play an important role in this regard.

There is nothing, in principle or in law, that prevents state/public media or commercial media from being “independent” in their journalism, free from political or corporate influence. But so long as they fail to fulfill this role adequately, independent media will be necessary as an alternative. How far independent media can fulfill this role may depend on how much readers and audiences feel they need them.

Writer: Virgil Hawkins

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://accounts.binance.com/en/register?ref=JHQQKNKN